Spy Plane Photos Open Windows Into Ancient Worlds

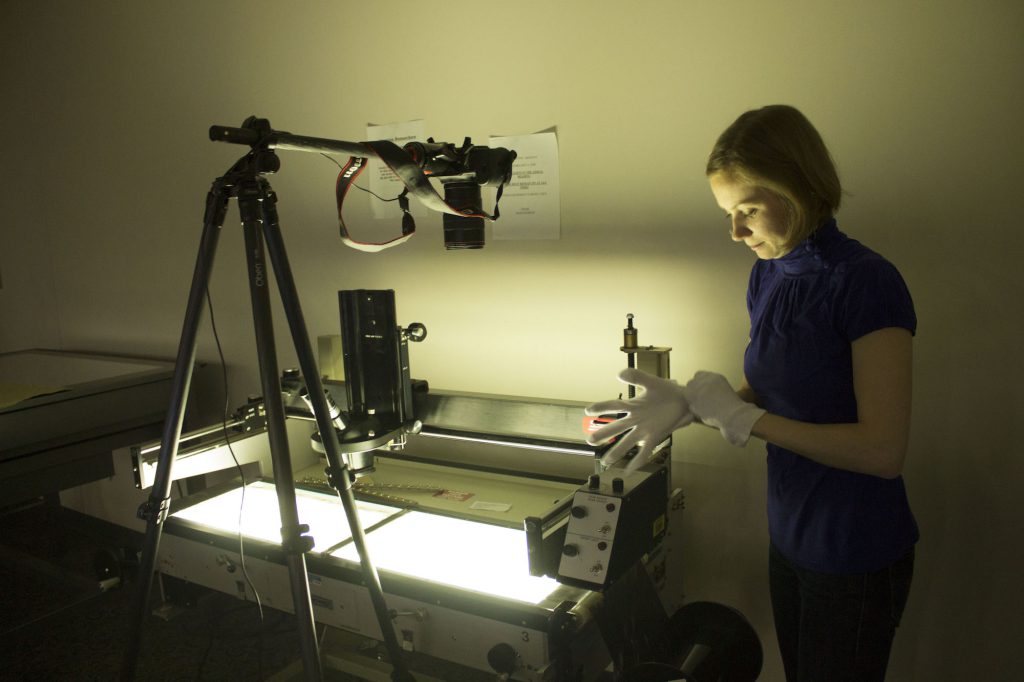

In a darkened room of the U.S. National Archives, we stood over a light table, a special backlit surface for viewing film. Our gloved hands slowly turned heavy metal rolls of 9.5-inch-wide film, unspooling our way back in time to the Middle East of the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Black-and-white negatives offered a bird’s-eye view of sinuous rivers lined with date palm tree gardens; villages ringed by agricultural fields; the occasional city, crowded with houses, markets, and mosques; and vast tracks of barren steppe-desert punctuated by dirt paths, isolated sheepfolds, or remote air strips. Among these rural and urban scenes, a careful viewer can also find traces of ancient and historical settlements and land use.

These images come from a special collection of footage. In the late 1950s, U-2 spy planes flew at around 70,000 feet over Cold War hotspots in Europe and Asia, capturing images that could show details as small as a person.

They aimed to cover places of interest for military intelligence such as foreign bases, airfields, and potential nuclear weapons facilities. But buried within the film rolls were high-resolution photos of historical, ethnographic, and archaeological sites and landscapes.

The U.S. government declassified many U-2 images in 1997, making them freely available to researchers and the public. But they remained unindexed and unscanned. There was no way to access the images digitally, nor could people know where geographically each roll of film was taken or highlight the particularly interesting frames.

In the past four years, my archaeologist colleague Jason Ur at Harvard University and I (a landscape archaeologist) have worked to make this complex photo archive accessible to other researchers and to illustrate its importance for history and anthropology. The result is a resource that we hope many scholars can take advantage of, a window into ancient sites as well as historical Middle Eastern communities as they existed more than half a century ago.

Many people wonder why we don’t just look at modern satellite imagery. Surely newer technologies, they think, provide the best photos?

Satellite imagery—as many people know from Google Earth—has increased in resolution in recent years, allowing us to see finer details when we look at our neighborhoods and parks from an aerial view. But for archaeology and history, the newest images are not always the best ones.

Archaeology, in many ways, is a race against time. Humans are continually transforming the earth’s surface, erasing traces of the past. The rate of those transformations has accelerated in recent decades.

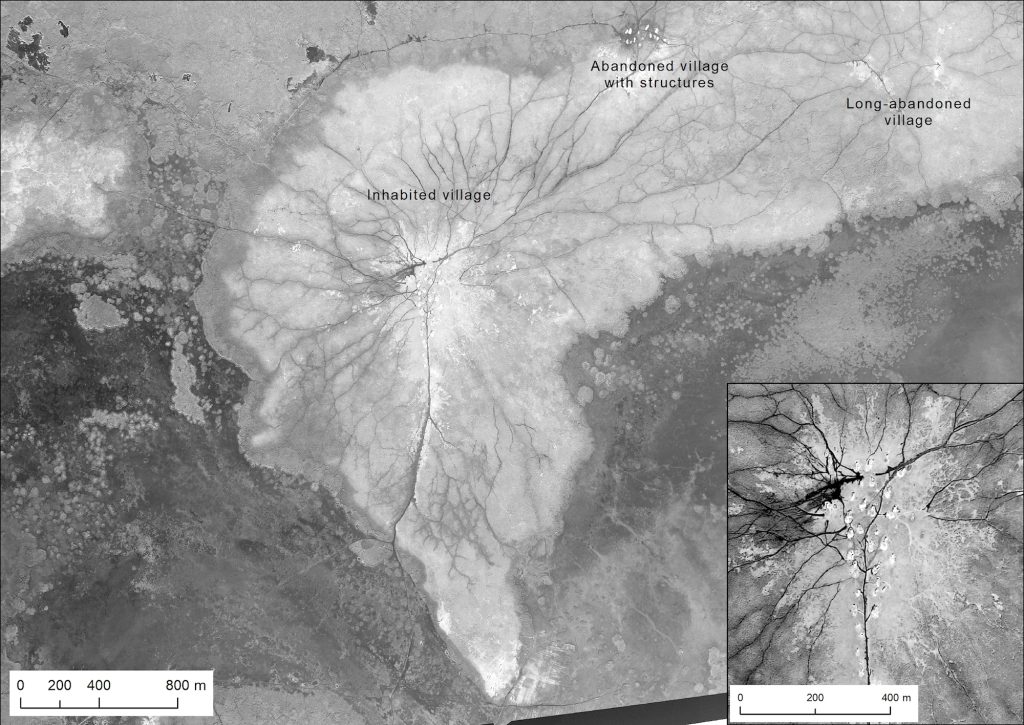

Old aerial images allow archaeologists to travel back in time. They transport us to the mid-20th century, before urban expansion, development, and agricultural intensification wiped away the surface traces of ancient communities, many of which had survived for millennia. Archival images can also provide a times series showing where 20th-century communities lived and how their lives and environments changed.

An observer can see things from the air that might not be obvious from the ground. The buried remains of ancient canals, fields, roads, or paths sometimes cause differences in the soils’ moisture, salinity, or chemistry. These changes in turn affect plant growth. Vegetation in the shallow but possibly moister soils above an old, buried stone wall, for example, may be thicker or thinner than plants just to the side in deeper, better-draining soils. The patterns created by such changes—such as long straight lines—are only noticeable when viewed from afar.

Scholars often liken it to the result of stepping away from the blobs of paint in an impressionist artwork. Take a few steps back and a meaningless cluster of colors becomes a woman with a parasol on a riverbank.

It isn’t a new idea for archaeologists and human ecologists to use historical aerial and satellite images. A lot of work has focused, for example, on images from the United States’ first-ever spy satellite program, CORONA, designed to image Cold War hotspots in a less dangerous way than from a U-2 airplane.

From the safety of space, CORONA cameras captured many high-resolution photos from 1967–1972. In 1995, then-President Bill Clinton declassified CORONA imagery and the images have subsequently led to the discovery of many fascinating archaeological features in the Middle East, such as 4,500-year-old road networks in northern Syria and paleochannels of rivers and canals modified over thousands of years in Iraq.

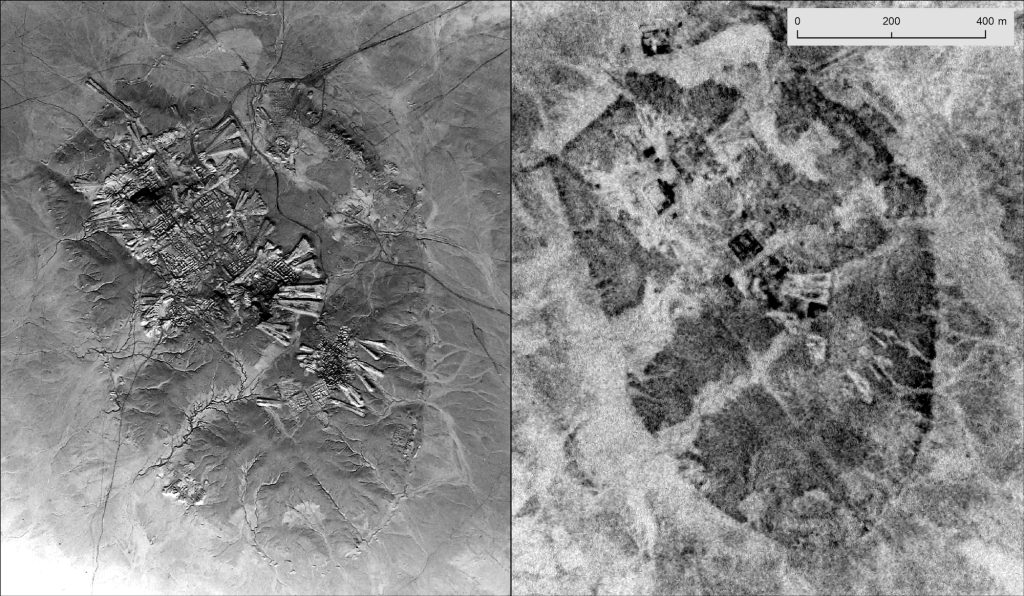

This imagery also has limitations. CORONA photos only have a resolution of about 2 meters per pixel, too grainy to see anything but the largest walls of ancient buildings.

Further, some parts of the Middle East had experienced so much development by the late 1960s that many archaeological surface traces had already been erased. I have worked with historical imagery throughout my career and have always wished for older, more detailed imagery than what CORONA could offer.

In late 2012, Jason Ur met Lin Xu, a digital imaging expert who had gone to the National Archives to hunt down U-2 images of his hometown in China. Ur invited me to take a look at the images, which can approach a resolution of 30–50 centimeters per pixel, comparable to or greater than the resolution of most of the best imagery on Google Earth today. When we saw the amazing quality of the photos, we knew that it would be worth the detective work it would take to build a systematic index.

The very first film roll I browsed in my initial trip to the archives in 2015 began with the usual rivers, steppes, and towns in grayscale. Then, partway through the roll, an intensely white negative frame came into view, brightening the whole room. With the turn of the spool, I was suddenly flying over the black basalt desert of the eastern panhandle of Jordan.

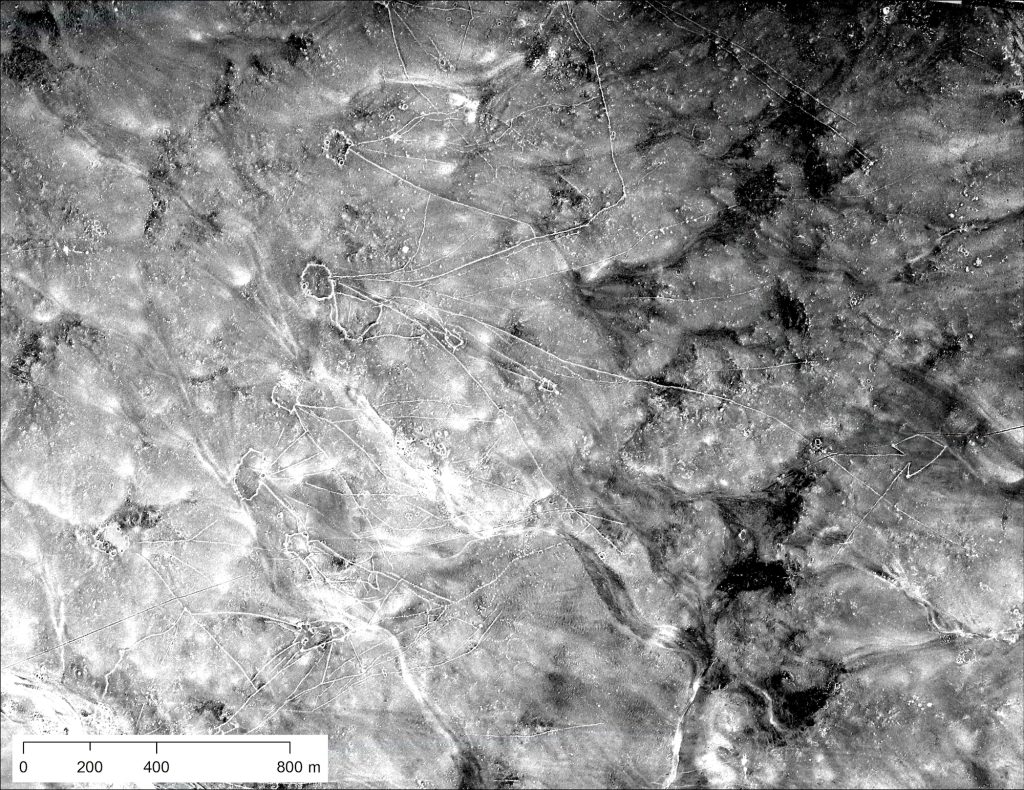

The negatives’ blinding brightness was caused by mesmerizing geological patterns: the desert’s dominant surface rock formations are dark, marbled by bands of lighter sediment deposits. But within this landscape, human hands had moved hundreds of stones into distinctive shapes.

Star, diamond, or cloudburst-shaped enclosures connected to long stone lines, marking ancient gazelle hunting traps called “desert kites.” More mysterious circular stone structures resembled spoked wheels. Clusters of dwelling foundations or animal corrals dotted the regions around the kites and wheels and also more empty areas. The region today is sparsely inhabited, but nearly every negative over hundreds of frames showed dozens of features evidencing earlier human activity.

These features weren’t previously unknown to archaeologists. But having so many high-resolution photos from so long ago and over such a broad area is a unique resource. I was stunned by the sheer number of structures and the clarity of the desert kites in the images.

The work in the archives is cumbersome sometimes. It would be tedious if it weren’t for the fact that the images are so interesting and occasionally beautiful.

As I turn the spool of a film roll, there is a sense of exploration and discovery: I can visually re-create the pilot’s journey. Sometimes the plane flies over regions I know by heart, and I almost hold my breath, hoping that the plane veers just a little to the right or left to capture a place I really want to see—but as it looked 60 years ago.

With the turn of the spool, I was suddenly flying over the black basalt desert of the eastern panhandle of Jordan.

To work with U-2 images, we first have to order film rolls from the National Archives’ “Ice Cube” preservation facility in Lenexa, Kansas, for delivery to the Aerial Film Section in College Park, Maryland. We unspool hundreds of meters of film over a light table, identify frames from sites already known to be of archaeological interest, photograph the negatives in pieces using a 100-mm macro lens, and then stitch them together and invert them in Photoshop.

Images taken from planes or satellites are distorted because the lens never has a perfectly vertical perspective. We geo-reference each frame in digital mapping software to geometrically correct it and give it real-world coordinates.

This process creates an image that we can use to map the particular place that it happens to cover. In addition, if we want to find U-2 frames covering a particular place, we have to generate a spatial index, which requires additional work.

We first tried searching CREST, the CIA’s database of declassified records, for documents concerning U-2 missions. However, the geographic coordinates in these documents were not very accurate, and some missions did not have declassified coordinates at all. If a CIA index of U-2 missions exists, it has not been declassified.

To generate our own spatial index, we turned to skinny 2.75-inch rolls of “tracking film” captured by a second camera on the U-2 planes. Unlike the main camera, which offers high-resolution images over stretches of the flight where it was activated by the pilot, tracking frames show low-resolution, horizon-to-horizon views under the plane throughout the entire flight. That means we have a much broader view, making it easier to recognize ground features. We matched this tracking film to modern satellite imagery to accurately reconstruct the path of the U-2 planes’ missions.

For example, we found that mission 8648 departed the İncirlik Air Base at Adana, Turkey, on October 30, 1959. It flew over western Syria, then over the desert to the Turkish border at Qamishli. The pilot turned east to visit Iraqi cities, made an extended detour south to Riyadh in Saudi Arabia, then returned to western Iraq. After following the Iraqi-Syrian border north, the plane snaked its way back across Syria to Adana in the late afternoon.

Throughout the almost nine-hour journey, the plane flew close to 7,000 km and captured 5,053 frames in 39 rolls of film, plus 1,006 frames from the tracking camera. Among this single mission’s photographs are amazing images of the ziggurat (temple pyramid) at the early Mesopotamian city of Ur, the walls of the Neo-Assyrian capital of Nineveh, and the ruins of the Abbasid Caliphate’s capital at Raqqa.

Nineveh (in modern Mosul, Iraq) and Raqqa (in Syria) have suffered over the last decades in the face of urban development, and, since 2014, from deliberate acts of destruction by the Islamic State. Today ancient Ur is in the middle of the desert, but U-2 photos show paleochannels of the Euphrates River surrounding the city—features that are no longer visible due to the massive expansion of the adjacent Tallil Air Base.

Mission 8648 photos also show ethnographically important environments and communities that have since totally disappeared: most significantly, the drained marshes of southern Iraq and hundreds of Marsh Arab villages within them. From the 1970s onward, these marshes progressively shrank as hydroelectric dams impounded the Tigris and Euphrates floodwaters that once sustained them.

In the 1990s, then-President Saddam Hussein systematically drained what was left, forcing marsh dwellers to abandon an ancient way of life. But the island villages, woven reed huts, networks of boat paths, and expansive reed forests that sustained that way of life remain preserved in U-2 photos.

In May 2019, we finally published our online, interactive guide for U-2 images of the Middle East, as well as a how-to guide for reproducing and working with the images.

The scale of this project is immense—both in terms of the work that we have already done and future work that others could do. The total number of U-2 missions is unknown but must be in the hundreds.

We worked with the available film generated by all Middle East missions for which the National Archives has declassified film. Just these 11 missions generated 357 rolls of film holding 46,561 frames. Over four years of work, we have processed a few hundred of these frames for our own research projects.

Right now, our index only covers the Middle East because we happen to actively conduct archaeological work there. But our published methods could be used by others to piece together indexes for other regions covered by the U-2 program, especially formerly Soviet Eastern Europe, the formerly Soviet Central Asian republics, and China.

We hope that the online resources we have created will enable other anthropologists and historians to search the U-2 photo archives for images relevant to their own research projects. For broader audiences, the photos provide a fascinating historical look at the Middle East—showing, for example, Old Aleppo long before the massive destruction wrought in the Syrian Civil War.

We believe the project exemplifies how open-access archival data from the U.S. government can benefit the public and researchers across disciplines—historians, environmental scientists, archaeologists, ethnographers, and more. Thanks to the U-2 program, anthropologists have an exciting new source of historical data on archaeological sites and landscapes—as well as the settlement and land-use patterns of 20th-century communities whose ways of life have since disappeared.