Reimagining Rock Art in Southern Africa

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

The Indigenous San communities of Southern Africa were originally hunting and gathering peoples. One of the greatest testaments to San history is the rock art found throughout the subcontinent.

The oldest rock art in Southern Africa is around 30,000 years old and is found on painted stone slabs from the Apollo 11 rock shelter in Namibia. Where our study took place—the Maloti-Drakensberg mountain massif of South Africa and Lesotho—rock paintings were made from about 3,000 years ago right into the 1800s.

For decades, people thought that one guess about the art’s meaning was as good as another. However, this ignored the San themselves.

We can deepen our understanding if we try to view rock art in terms of San shamanistic beliefs and experiences. Advances in ethnography (literature produced by anthropologists who work with San people) help convey the San worldview to rock art researchers.

By locating new sites—thousands are still to be found—and revisiting known ones in the light of developing insights, we can go much further than guessing.

New insights from old images

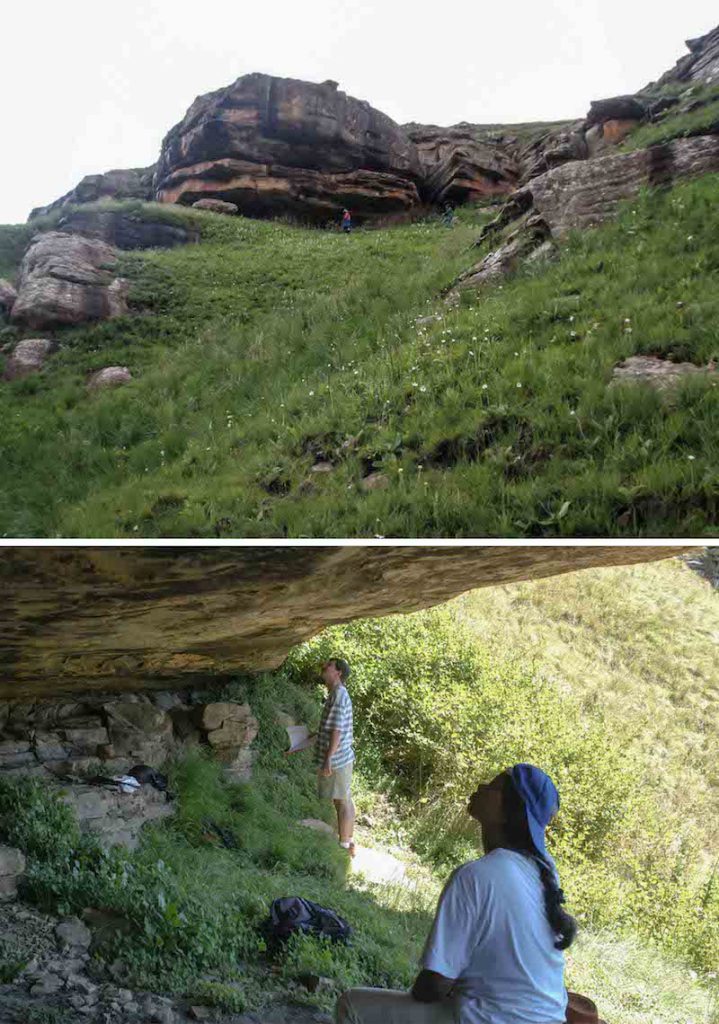

We reinvestigated such a site in the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg mountains. It was first described in the 1950s and is recorded as RSA CHI1. At first glance, the ceiling panel seems to be a confusing collection of paintings of antelopes and human figures, some of which are painted on top of others, in shades of earthy reds, yellow ochres, and white.

In 2009 and working under challenging circumstances, South African artist and author Stephen Townley Bassett produced a documentary copy of the ceiling panel. It shows the beauty and mystery of the art.

When we looked at his copy, we found that the significance of some images on the site’s ceiling panel had been missed by other researchers. This allowed us to examine the meaning of these images more closely.

Importantly, our realization was not a technological or methodological advance. Instead, it was a conceptual development that occurred by turning our attention to a well-known site and viewing it again in the light of everything we have learned so far about San rock art.

Our reinvestigation allowed us to arrive at a new understanding of specific elements of San belief.

Deeply religious art

Two sources of San ethnography are especially important in rock art research and our understanding of the ceiling panel. In the 1870s, the German linguist Wilhelm Bleek and his co-worker and sister-in-law Lucy Lloyd interviewed a series of |Xam San people, some of whom had been brought from the Northern Cape to Cape Town as convicts.

Remarkably, Bleek and Lloyd recorded over 12,000 pages of texts in the |Xam language, which is no longer spoken, and transliterated most of it line-by-line into English. Much of this material remains relevant to our understanding of the art.

More recently, in the 20th century, a number of anthropologists worked with San groups in Namibia and Botswana with a focus on a range of topics from hunting and gathering to folklore and child care. The Kalahari ethnography complements the Bleek and Lloyd archive.

We know from the ethnography that the San believe in a universe with spiritual realms above and below the level on which people live. Decades of research has shown that the rock art is deeply religious and situated conceptually in the same multilevel universe.

Rereading the ceiling

In San rock art, the eland is a connecting element. It is the most commonly depicted antelope in the uKhahlamba-Drakensberg paintings. It is featured in several San rituals and was believed to be the creature with the most !gi:—the |Xam word for the invisible essence that lies at the heart of San belief and ritual.

At RSA CHI1, there are many depictions of eland, but we focused on the one with its head sharply raised.

Depictions of this posture, though not common, recur in other sites. The eland’s raised head suggests that it is smelling something, most probably rain. Both smell and rain are supernaturally powerful in San thought.

The unique feature in this paintings is, however, the way in which a line runs up from an area of rough rock, breaking at the eland’s front legs, and then on to another area of rough rock. The painter, or painters, must have depicted the eland first and then added the line to develop the significance of its raised head. We argue that both the raised head and the line emphasize contact with the spirit realm, though in different ways.

The way in which the painted line emerges from and continues into areas of rough rock is comparable to the way in which numerous San images were painted to give the impression that they are entering and leaving the rock face via cracks, steps, and other inequalities. But what lay behind the rock face?

Behind the rock face

We have noted already that the San universe is divided into different realms. Contact between these often interacting realms is sometimes depicted in the art by long lines that link images or sometimes appear to pass through the rock face. San shamans or medicine people (called !gi:ten in |Xam) move along or climb these “threads of light” as they journey between realms to heal the sick, make rain, and perform other tasks. The |Xam called these out-of-body journeys |xãũ. They obtained the power needed to accomplish them by summoning potency from strong things, such as the eland.

The inter-realm nature of the line is further evidenced by the three creatures depicted moving along it. The two moving upward are quadrupeds or four-legged animals: One is nonspecific, and one has a tail and human arms. These images may depict the sort of bodily changes that !gi:ten say they experience during out-of-body journeys.

The faint white creature moving down the line was for us the climax of our work. It is clearly birdlike (!gi:ten often speak of flying). But closer inspection revealed that, though faint, it has a rhebok antelope head with two straight black horns, a black nose, and mouth.

It also has two “wings” emanating from its shoulders. In short, it is a hybrid form—part bird and part buck. In addition, it has two white lines coming out of the back of its neck. It was from this spot that !gi:ten expelled the sickness that they drew out of the bodies of sick people.

For many people, the detail and the complexity of the images at this site come as a surprise. Yet they are typical. San rock art ranks among the best in the world if we consider its beauty, its intricacy, and the rich sources of explanation on which we can draw.