What Pots Say—and Don’t Say—About People

A GRAVE WITH A POT

“Who made this?” the village liaison, Rudini Wallay, asked as he pulled porcelain fragments from the screen used to shake excavated dirt off archaeological finds.

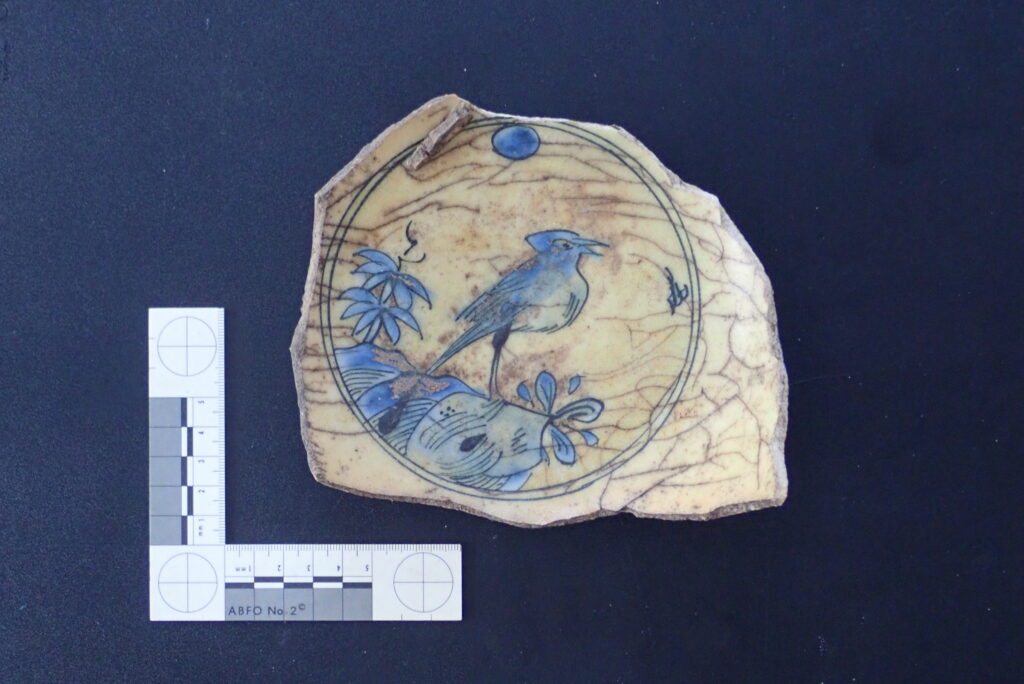

We were on Ujir, an island in eastern Indonesia, in 2018. Our shovel had struck pieces of a bowl painted with birds, flowers, and a landscape in blue and white. Not just that, though: a skull protruded from the other side of the hole. We had started to expose a burial. Tools down.

We knew that the spirit world is very much alive on Ujir. We carefully filled the hole and went to consult with the village mayor.

“You closed the hole? No problem then,” said the mayor. “Just don’t dig there anymore.”

“Of course not,” I said. “But there’s something else. We found pieces of this bowl in the same place. It may connect to the burial. Should I rebury it?”

Eyeing a fragment, the mayor replied: “You’re here to study broken things, aren’t you? Well, this is broken. No need to rebury it. Tell me, where is it from?” His question wasn’t so different from Rudini’s. Could the porcelain tell us something about the person who made it or perhaps the one who lay in the ground beside it?

This is an old but still relevant archaeological problem, what scholars call the “are pots people” question: How much of someone’s identity can we determine from the things they left behind?

We archaeologists have tried to connect materials with less tangible aspects of people’s culture from the field’s beginning. Many early attempts proved misleading as new evidence arose. In some cases, though, thinking about pots as links to people can add meaning to an otherwise dry explanation.

CONSENSUS AMONG POT MAKERS

The idea is intuitive: Sometimes due to their environments or perhaps from random chance, distinct groups of people make the same basic item differently.

This is especially true with pottery. A potter can mold clay into any shape, add sand or other material, decorate it, and fire it in different ways for a spectacularly broad range of qualities. Apart from holding something, and perhaps withstanding heat, there are few absolute requirements for what a pot should be.

However, archaeologists often come across pottery that looks standardized, although it is not mass-produced. Some powerful force must have kept the pots from one place—or from many places across space and time—looking alike.

That force is social learning: knowledge and beliefs about how to do things pass from person to person within socially connected groups. If we see distinctive features repeated in pots (or stone points, beads, baskets, and more) in a particular society, there must have been some consensus about how to make them that was transmitted through social learning.

Then, it follows, perhaps the pot makers also agreed on other things: language, the best way to live, a shared idea of how the universe came into being? It’s not absurd to think that a pot might signify a broader set of values or even group identity.

POTS DON’T EQUAL PEOPLE

Beginning in the 19th century, archaeologists set about classifying Neolithic cultures—the first groups to practice agriculture and pottery making—based on the material they left behind. The archaeologists noticed differences in stone tools and sites. But most distinct were the pots. So, the scholars invented names for past peoples based on these artifacts.

Perhaps the most famous of these is the Bell Beaker culture: Its pots, contracting in the middle and flaring at the mouth, appeared all over Europe and in North Africa roughly 5,000 years ago.

European and U.S. scholars of the 19th and early 20th centuries largely came from countries steeped in imperialism. Consequently, the spread of a particular type of artifact like the bell beaker suggested a group of people expanding into new territory and eliminating or absorbing whoever lived there before until a new culture and its pots arrived to repeat the process. Perhaps, they thought, this meant colonization was part of the natural order.

For bell beaker peoples, later research complicated the story. For example, DNA analyses of skeletons from sites across Europe suggests that in many cases, bell beaker material culture spread into new areas without large-scale human migration. Often the makers of these pots were not genetic newcomers; rather, for some reason, they adopted the new bell beaker style.

In Island Southeast Asia, where I work, a similar story once dominated archaeological scholarship: A migration of people and pottery arrived in the Philippines from Taiwan about 4,000 years ago and colonized eastern Island Southeast Asia 500 years later.

Based on the dates for the earliest earthenware, and patterns in modern languages, the idea took hold that a new Austronesian ethnic group brought pottery and a package of other technologies, including agriculture and deep-sea fishing with them. As they colonized new islands, the story went, they supplanted prior residents.

As archaeologists uncover more sites in Island Southeast Asia, though, it has become evident that traits like agriculture and deep-sea fishing appeared thousands of years before the earliest pottery—and in wildly different places. The pottery timeline has also become more complex.

The idea of one culture bringing all these technologies no longer holds.

THE PAST THROUGH PORCELAIN

This is not to say the pots/people assumption is worthless: Take porcelain. Making quality porcelain was so difficult that, at first, only a few places in China could do it. The city of Jingdezhen boasted the most famous kilns; for a few hundred years, beginning in the 11th century, a bright blue-and-white vessel almost certainly came from there. Some pots even have dates and artists’ signatures inscribed on the base—it’s hard to get a more precise link from pot to person than that.

The development of this porcelain took the resources of an imperial state and a network of patrons who could pay eye-watering sums. It may have been worth it: Blue-and-white ware was otherworldly. Renaissance Europeans spent centuries on maddening, futile attempts to replicate it.

But by the 15th century, kilns in Vietnam were turning out decent imitations. The technology diffused; the pots/people connection started out strong but became fuzzier over time. Eventually, cheaper imitations flooded the common market. And some ended up in Indonesia.

Back on the island of Ujir, the fragment of the porcelain bowl we found provided some hints about the buried person. In context, it was clearly a prestigious belonging: rare and visually stunning compared to the local pottery. But I could tell it was a later copy.

On the base was something resembling a Chinese character, though it meant nothing. This was for customers who knew to look for a mark but could not read Chinese script.

Yet, on Ujir, the bowl would have been special. Archaeologists usually find local pottery on the island made over an open fire, sometimes decorated with incised patterns, but always the same earthy colors. Porcelain could only be obtained from far away—and not cheaply. So, such vessels usually show up as treasured heirlooms, as offerings in sacred places, or in burials.

“Are pots people?” is not a straightforward question with an easy answer. Rather, it’s a thought experiment that every researcher of material culture should run repeatedly, with as much contextual information as possible. Perhaps the correct answer most of the time is “no.” But there are exceptions. For example, in cases where the difference in access to a desired technology is too great, people are good at reproducing something they see as valuable.

At the same time, present-day people often underestimate how much those in the past traveled and traded. The end user may have lived a vast distance from an artifact’s point of origin. What can such a well-traveled artifact tell us about the people who left it in the ground? Its culture of origin may be less important than how it fit into life where it was found.