Who Started the First Fire?

In the 1981 movie Quest for Fire, a group of Neanderthals struggles to keep a small ember burning while moving across a cold, bleak landscape. The meaning is clear: If the ember goes out, they will lose their ability to cook, stay warm, protect themselves from wolves—in short, to survive. The film also makes it obvious that these Neanderthals do not know how to make fire.

During the Middle Paleolithic, roughly 250,000 to 40,000 years ago, when Neanderthals occupied Europe and much of western Asia, the climate included a couple of major warm periods similar to today, but was dominated by two major cold periods that included dozens of shifts between cold and very cold conditions. Quest for Fire presented a generally accurate portrayal of Europe during one of the cold periods (80,000 years ago, according to the film’s title card), but almost all researchers agreed that the movie was flat-out wrong in its suggestion that Neanderthals were incapable of making fire. Now, new fieldwork our team has done in France contradicts some long-held assumptions and shows that the film might have had it right all along.

Conventional thinking has long held that our human ancestors gained control of fire—including the ability to create it—very early in prehistory, long before Neanderthals came along some 250,000 years ago. For many researchers, this view has been supported by the discovery of a handful of sites in Africa with fire residues that are more than a million years old. But it has also been buoyed by the simple logic of one idea: It is hard to imagine that our ancestors could have left Africa and colonized the higher, and often much colder, latitudes of Europe and Asia without fire.

The Neanderthals, after all, lived in Europe during multiple periods in which seasonal temperatures were similar to those that exist today in northern Sweden. (Northern Europe was covered in massive ice sheets during those periods.) There were vast, frigid grasslands populated by herds of reindeer, horses, and woolly mammoths. Fire would have allowed Neanderthals to cook those animals, making the meat easier to chew and more nutritious. And, perhaps more importantly, it would have helped the Neanderthals stay warm during the coldest periods.

This line of thought is the basis for the long-prevailing notion that our ability to make fire began long before the Neanderthals, as a spark—a single technological discovery that spread widely and quickly and has remained essential to human life, in an uninterrupted line, to the present day. But more recent evidence—some of it coming from our own fieldwork—indicates that hominins’ use of fire was not marked by a single discovery. It more likely consisted of several stages of development, and while we don’t yet know when these stages occurred, each of them may have lasted for hundreds of thousands of years.

We surmise that during the first stage, our ancestors were able to interact safely with fire; in other words, instead of simply running from it, they had become familiar with how it works. To get a deeper understanding of this stage, we can look to research done on chimpanzees—our closest living relatives—by Jill Pruetz, a primatologist at Iowa State University, who has studied chimps’ interaction with wildfires in West Africa. Pruetz has found that chimps clearly understand the behavior of fire enough to have lost the fear of it that most animals typically possess. In fact, Pruetz has observed chimps monitoring the progress of a passing wildfire from a few meters away and then moving in to forage in the burned-out area. So while chimps cannot build or contain fires, they understand how fire moves across the landscape, and they use this knowledge to their benefit. It is not hard to imagine a similar scenario playing out among small groups of our own early ancestors, perhaps the australopithecines, who lived from around 4 million years ago until about 2 million years ago in East Africa. The first stage may have persisted throughout much of prehistory.

The second stage would be when people could actually control fire—meaning they could capture it, contain it, and supply it with fuel to keep it going within their living areas—but they were still obtaining it from natural sources like forest fires. It is difficult to establish when this stage occurred, for a couple of reasons. One is that some claims for very old fires were simply incorrect. For example, at the famous Chinese site Zhoukoudian, what were originally thought to be the remains of 700,000-year-old Homo erectus fires turned out to be natural sediments resembling charcoal and ash.

Second, and perhaps most crucial, is that some of the earliest fire residues have been found in open-air settings—not inside caves—and consist of isolated fragments, small scatters of burned bones, or patches of discolored sediments. While it is possible that these residues are the remains of hominin campfires, it is equally possible, if not probable, that they were produced by naturally occurring wildfires. Every year, lightning causes tens of thousands of wildfires across Africa, Asia, and Europe. In the past, some of these would have burned the remains of hominin camps, including bones, stone tools, and sediments. In such cases, the fire residues have nothing to do with hominin occupation of the sites.

During the final stage, humans learned how to make fire, but again, we are not yet sure when this happened. Starting about 400,000 years ago, we begin finding much better evidence for human-controlled fire, such as intact campfires, or “hearths,” that contain concentrations of charcoal and ash inside caves, where natural fires don’t burn. Furthermore, the number of sites with such evidence increases dramatically. So it is clear that by this time, some hominins in some regions could manage fire and thereby control it, but whether they could make it remains an open question.

Between 2000 and 2010, our research team—made up of three Paleolithic archaeologists who focus on stone tool technology and two geoarchaeologists who study how archaeological sites form—excavated two Middle Paleolithic sites, Pech de l’Azé IV and Roc de Marsal, in the Périgord region of southwestern France. Pech IV and Roc de Marsal are caves that were regularly used as campsites by small groups of Neanderthals from 100,000 to 40,000 years ago, which is about when Homo sapiens, modern humans, arrived in Europe.

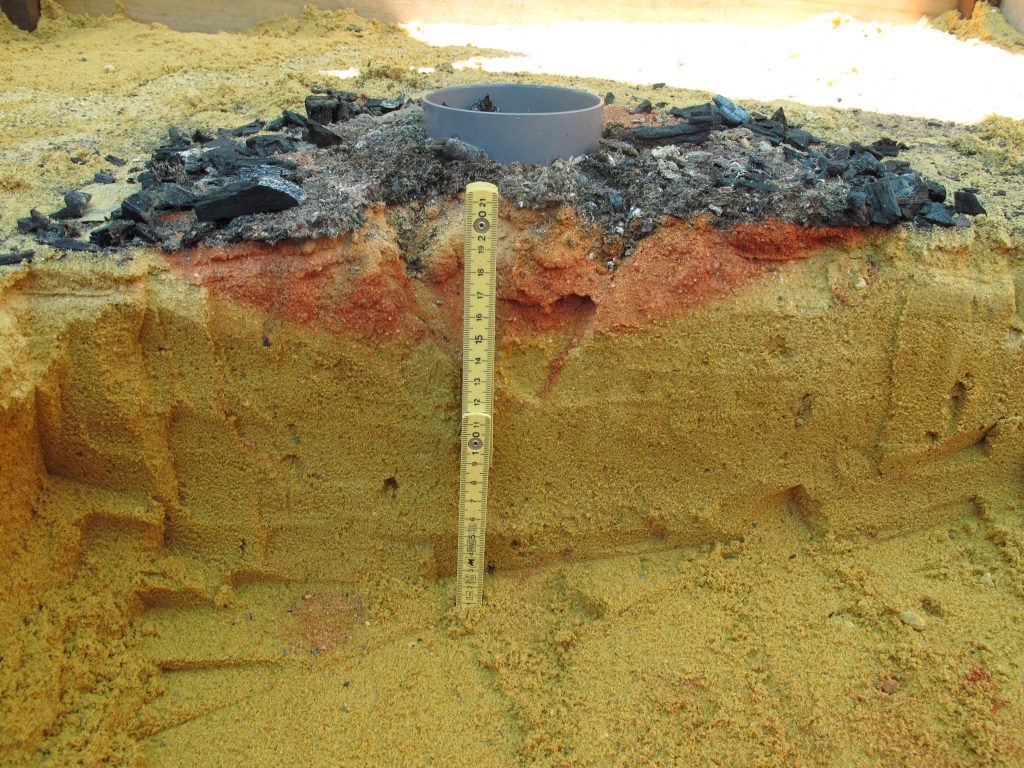

One of the more interesting discoveries we made during our years of excavating Pech IV was strikingly abundant evidence of fire use. In the lowermost deposits, those resting directly on the cave’s bedrock floor, we found a 40-centimeter-thick layer full of charcoal, ash, and burned artifacts marking where individual campfires had been built 100,000 years ago. There were also thousands of stone tools, many of which had been incidentally burned by nearby fires. (Paleolithic people were producing, using, and discarding stone tools on a daily basis, so their occupation sites are full of these artifacts—along with bone fragments from their prey animals—which were eventually buried under sediments that accumulated over time. Later people who used the sites could not help but build their fires on top of concentrations of discarded tools and bones.)

We found similar evidence at Roc de Marsal, which also has a thick sequence of successive layers containing tens of thousands of stone tools and the bones of butchered animals. Just as at Pech IV, the oldest layers at Roc de Marsal contained abundant evidence of fire, including dozens of intact hearths so well-preserved that they looked like they could have been abandoned just days before.

We were not surprised to find signs of fire at these two sites, since other, even older sites also offered good evidence of fire. And given the prevailing notion of a spark—that once fire-making was “discovered” it quickly became part of everyday life—we simply assumed that the Neanderthals at Pech IV and Roc de Marsal knew how to make fire.

However, other evidence from these sites soon led us to question that notion. For one, neither site showed signs of fire in its upper layers. At first, we speculated that since Paleolithic people tended to live right at the mouths of caves, wind or water had removed the fires’ ephemeral traces, like charcoal and ash. At the same time, however, almost none of the thousands of stone tools and animal bones we found in these upper layers were burned. If fire had been present, these objects would have been altered by the heat. Erosional processes like wind and water, after all, cannot selectively remove burned objects and leave behind unburned ones. It was clear, then, that fire had almost never been used at these sites in the later periods.

This seemed strange, especially because the older layers dated to a warm climatic period, while the more recent layers—the ones without fire—were deposited between 70,000 and 40,000 years ago, a time of increasing cold as glaciers again spread across much of Europe. This raised some really interesting questions: Why did Neanderthals stop using fire during cold periods, when the need for warmth would be most important? And if they were using fire only in the warm periods, what were they using it for? Cooking would be one possibility, but then why did they not cook their food during the colder periods?

Having fires in warm periods and not in cold periods made little sense. It’s not just a question of having fuel available. While trees are much more common during warmer periods, animal bone, which is also an effective fuel (and was used for the fires at Pech IV), is abundant during both warm and cold periods. This leaves one possible explanation: The Neanderthals at this time were still in the second stage of interacting with fire—they were collecting naturally occurring fire when it was available but did not yet have the technology to start fires themselves.

It is well-known today that natural fires from lightning strikes occur much more frequently in warm conditions—whether in more temperate places or during warmer parts of the year. Similarly, lightning would have been much more prevalent during the warmer phases of the Pleistocene Epoch (which lasted from roughly 2.6 million years ago to around 10,000 years ago) than during the colder periods. If the Neanderthals lacked the ability to start fire themselves and could thus only obtain it from natural fires, then we would expect to find much more evidence of hearths during warmer periods and less during colder ones. Which is why it is likely that Neanderthals had not yet entered the third stage of interacting with fire. That technological development occurred either elsewhere or at a later time.

The evidence from Pech IV and Roc de Marsal clearly shows that the Neanderthals at these sites lived without fire not only for long periods but also during the coldest periods. This alone raises even more questions about how they were able to survive. There is no clear evidence that they could make clothing (although some researchers today seem to think Neanderthals were likely making some articles of clothing, even if they were very crude), so perhaps an old theory about Neanderthals—that they were really hairy—is correct. (This notion, from the early 1900s, was discarded in later decades because it was seen as dehumanizing Neanderthals.) It might also mean that they relied more on food—especially meat—that did not need to be cooked.

So while we are obligate fire users today—we could not survive without fire in some form—Neanderthals, according to our research, had no such dependence. Perhaps fire dependency arose later, in the Upper Paleolithic (40,000 to 10,000 years ago), and it is almost certain to have existed by the time agriculture developed at the beginning of the Neolithic period (roughly 10,000 years ago in the Middle East). But there is still much we do not know.

If chimpanzees can effectively interact with wildfires, can we assume that the same was true for some of the earliest hominins, such as Australopithecus afarensis? When did our hominin ancestors first start to collect burning material and carry it back to their campsites, as portrayed in Quest for Fire and as probably practiced by Neanderthals? And, of course, when did humans first learn how to make fire? These are just a few of the mysteries that remain unsolved.

The ability to take advantage of the properties of fire is one of the most important technological advances in our evolutionary past. What we are realizing now, however, is that it was not the result of a single accident or stroke of genius. It was, instead, a process that likely unfolded over hundreds of thousands of years. And for the Neanderthals, the process was punctuated by periods of intense cold in which, when the benefits of fire would have been greatest, they simply had to make do without it.

Toward the end of Quest for Fire, a young Homo sapiens woman teaches a small group of Neanderthals how to start a fire by using the hand-drill technique to create an ember. While it is certainly possible that modern humans developed fire-making technology before arriving in Europe, and perhaps even shared it with Neanderthals, such a scenario remains, at this point, pure speculation.

What has become clear, however, is that before Homo sapiens arrived in Europe, our Paleolithic cousins didn’t just spend a few months or years in a cold land without fire—they spent entire lifetimes, many generations even, without the warm glow of a hearth to take the chill off their toes, cook their meat, and lift their spirits.

This article was republished at The Atlantic.