What’s Behind the Evolution of Neanderthal Portraits

NEANDERTHALS’ FIRST PORTRAITS

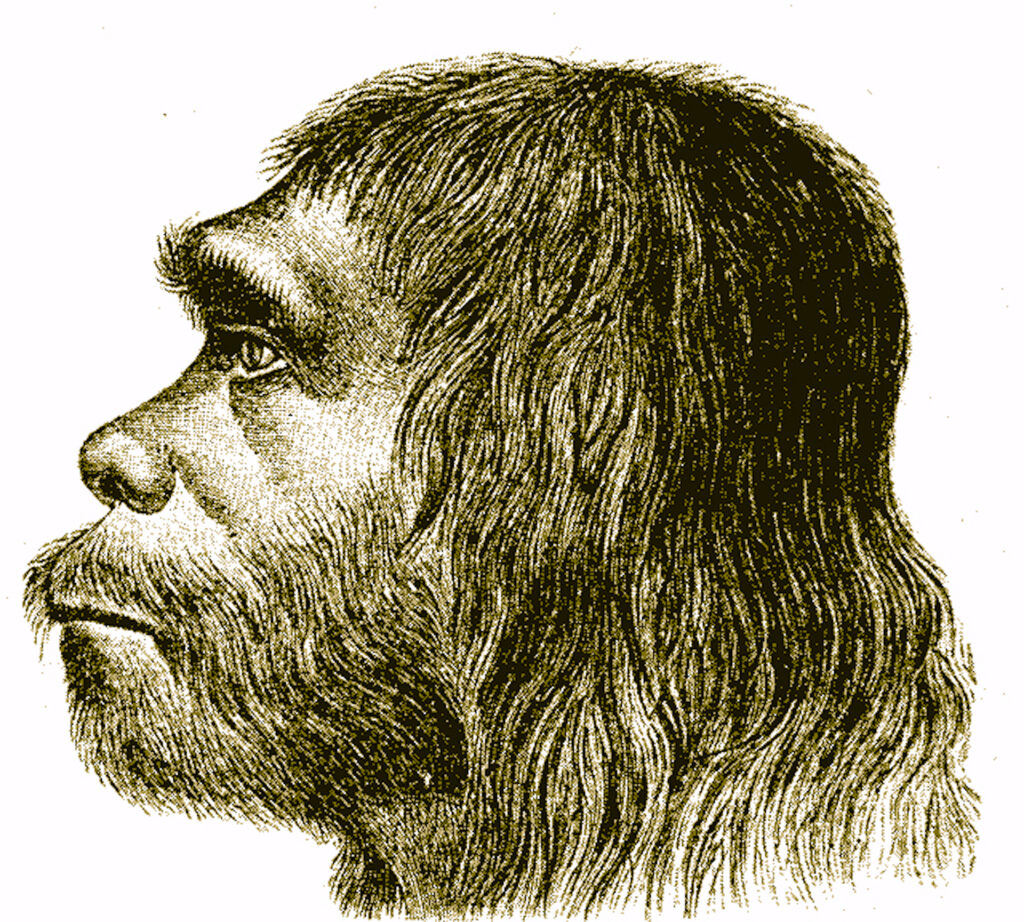

In 1888, a few decades after the first scientifically named Homo neanderthalensis fossil surfaced, anthropologist and anatomist Hermann Schaaffhausen made a portrait of what that Neanderthal might have looked like in life.

Found in Germany’s Neander Valley, the actual fossil was just the top of a skull—a teardrop-shaped dome fronted by big brows—without the facial bones below. But Schaafhausen filled in the blanks and sketched a Neanderthal visage in profile: a hairy, husky fellow with a protruding jaw.

Eighteen years earlier, scientist Louis Figuier published an illustration that depicted the Neander Valley individual as a biologically modern, fur-clad European. From the same fossil, two contemporaries drew diametrically opposed images.

Why did this happen?

As a social Darwinist, Schaaffhasuen believed various races represented different stages in a linear progression of human evolution. To him, Neanderthals belonged to a primitive stage of cave dwellers. Gorilla-like and uncivilized, Schaaffhausen’s Neanderthal begged for physical and moral betterment. Figuier, a creationist, viewed Neanderthals as humans like us—manifested by a Biblical God on the sixth day of creation. He envisioned Neanderthals as biologically modern, but—like babies—needing to learn the ways of civilization.

Since this early set of illustrations, plenty of ink and paint has been spilled over the interpretation and depiction of Neanderthals. These images must be situated within their historical contexts. When looking at Neanderthal reconstructions—and scientific illustrations at large—it is important to unpack how social and political views color the rendering of evidence.

Interpretations sometimes say more about their makers than their subjects.

UNCANNY COUSINS

Neanderthals, our evolutionary cousins, diverged from our lineage around 600,000 years ago. They roamed Eurasia for hundreds of thousands of years until they went extinct around 40,000 years ago. In many ways, they resembled our Paleolithic ancestors: Both used stone tools, cooperated, and took care of their kind. But distinctions stand out. Stockier and endowed with massive brows, Neanderthals survived some of Eurasia’s coldest conditions where no Homo sapiens ventured during those cold spells.

What Neanderthals looked like has always mattered. More than just accompanying artwork, Neanderthal visualizations represent a touchstone for what it means to be human.

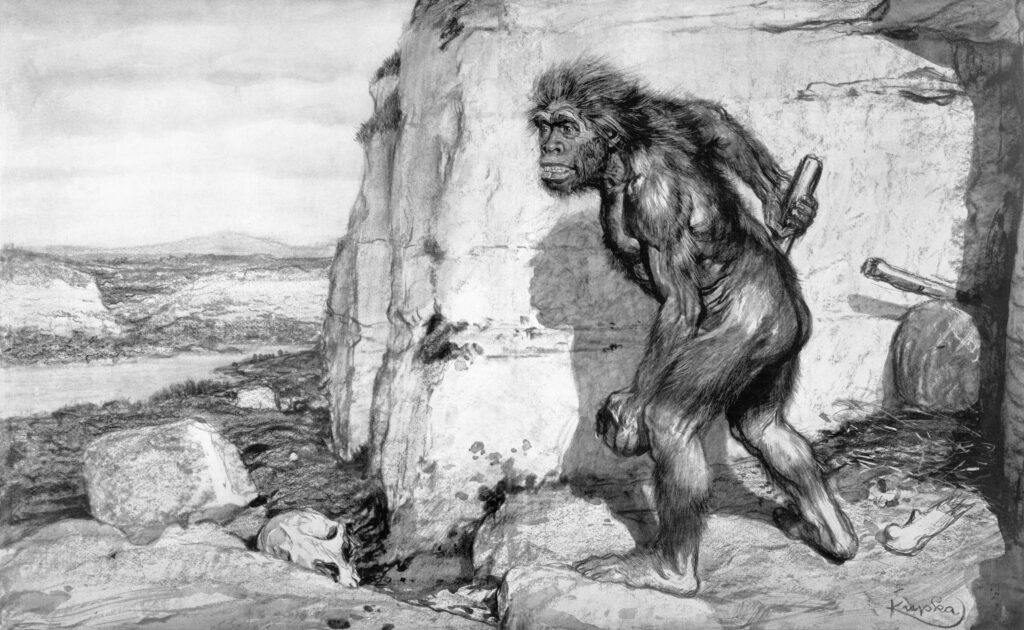

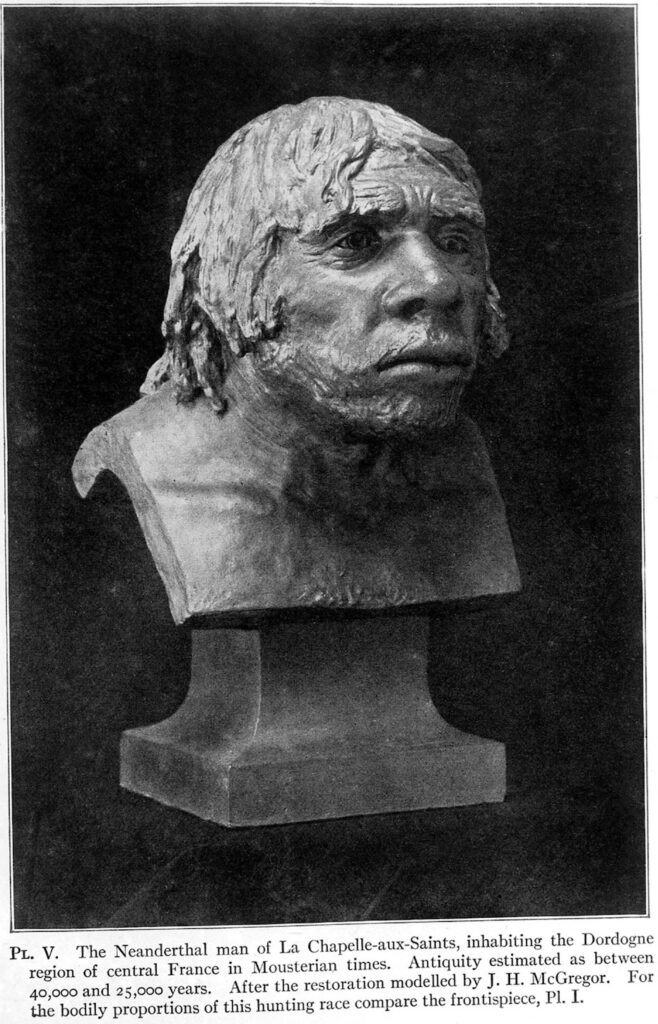

Before the 20th century, only scattered bones of Neanderthals had been discovered. The first nearly complete skeleton was found at the French site of La Chapelle-aux-Saints in 1908. The French paleoanthropologist Marcellin Boule analyzed the fossils and placed Neanderthals closer to monkeys and apes than humans. An image, based on his conclusions, showed a hairy, stooped ape-like figure holding a club and stone.

In contrast, British anatomist Arthur Keith thought that Neanderthals belonged to the European lineage. This was not a gesture of inclusivity: Keith, a proponent of scientific racism, believed that humankind originated in Europe. He worked with an artist to produce a Neanderthal illustration that, just like Figuier’s, looked like a European man. The figure sat by a fire making stone tools while wearing fur clothes and a necklace.

Boule’s ape-like man met an evolutionary dead end. Keith’s nearly European Neanderthal figured into human history.

Despite differing stances about Neanderthals’ place in human evolution, both perspectives were influenced by imperialism and the popularity of “race science.” According to this now debunked and denounced view, races were seen as biologically distinct groups that could be organized into a hierarchy. Neanderthals became a tool to further this ideology.

The horrors of World War II shifted perspectives on race and imperialism in public and academic spheres worldwide. Scientific racism retreated in the face of widespread criticism of the notion that certain living populations could be deemed biologically, intellectually, and culturally inferior.

In this post-war era, William Straus Jr. and Alexander Cave re-examined Boule’s original analysis of the La Chapelle-aux-Saints Neanderthal. In 1957, they detailed inaccuracies of the early interpretation. The work led them to believe that if a shaved, bathed, and well-dressed Neanderthal rode a New York City subway, “it is doubtful whether he would attract any more attention than some of its other denizens.”

With a push toward a more united perspective on humanity, Neanderthals were welcomed into the fold.

FLOWERS AND FEMALES

A major shift in Neanderthal perceptions occurred in 1971 when archaeologist Ralph Solecki reported on excavations in Shanidar Cave, Iraq. His work suggested Neanderthals cared for ailing kin and buried their dead with flowers based on the presence of pollen. He famously commented on Neanderthals that “although the body was archaic, the spirit was modern.” Although more recent research has shown the pollen likely came from burrowing rodents, Solecki’s report had a profound impact on perceptions of Neanderthals at the time.

Later that year, an illustrated nonfiction book for the public brought the Neanderthal flower people to life. In the book, Neanderthals held feasts and funerals. This updated, more human-like Neanderthal garnered the backing of scientists and increasing public sympathy.

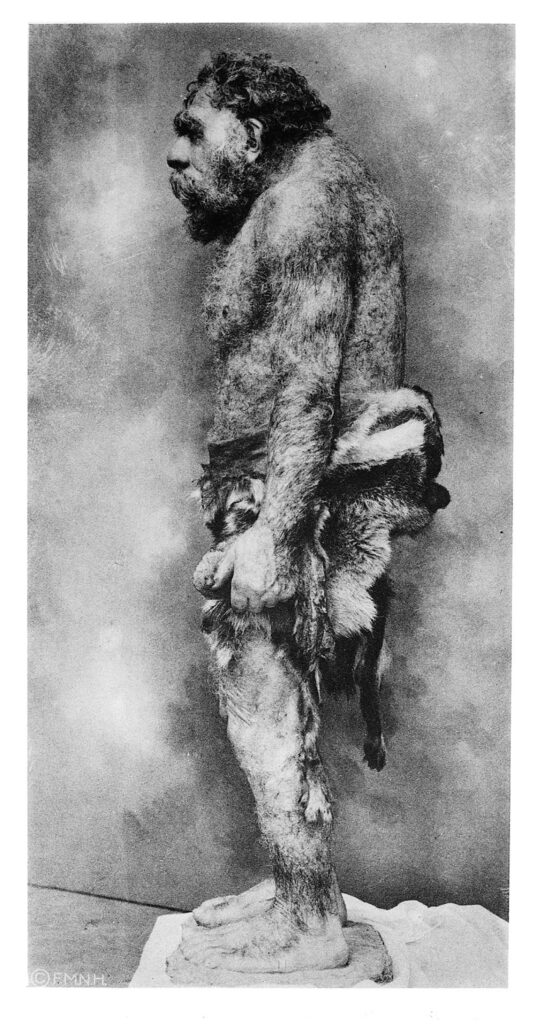

For the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, the Field Museum commissioned sculptor Frederick Blaschke to create Stone Age dioramas, which included this figure of the Neanderthal from La Chapelle-aux-Saints, looking ape-like.

Wellcome Images, CC BY 4.0/Wikimedia Commons

A 1920 mural in the American Museum of Natural History, which was created under the guidance of paleontologist Henry Fairfield Osborn, displays brutish Neanderthals with bent knees, like upright-walking apes.

Charles Knight/American Museum of Natural History/Wikimedia Commons

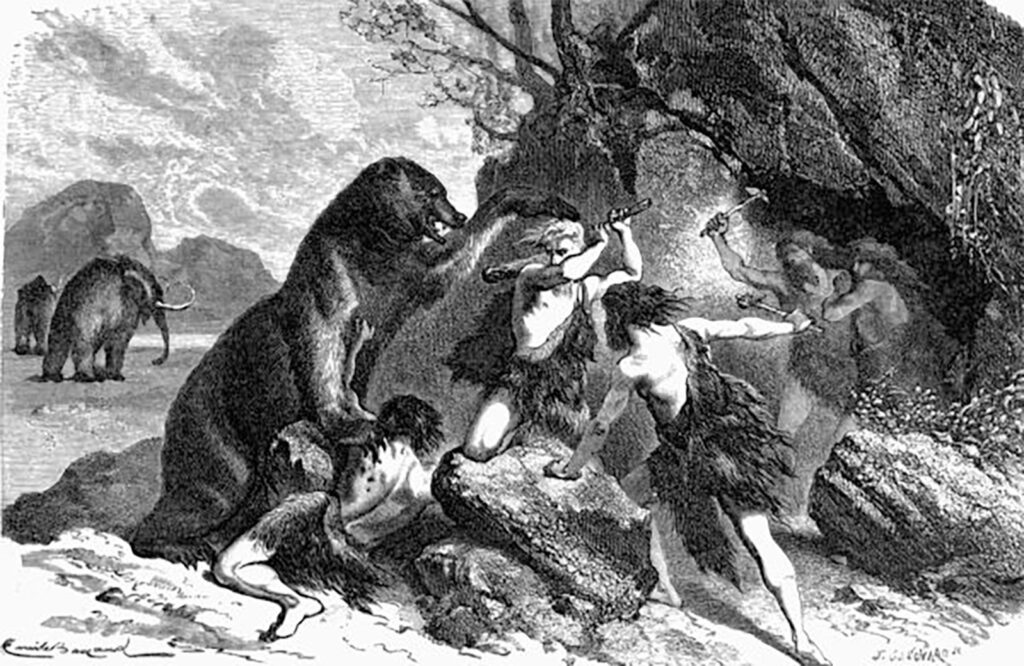

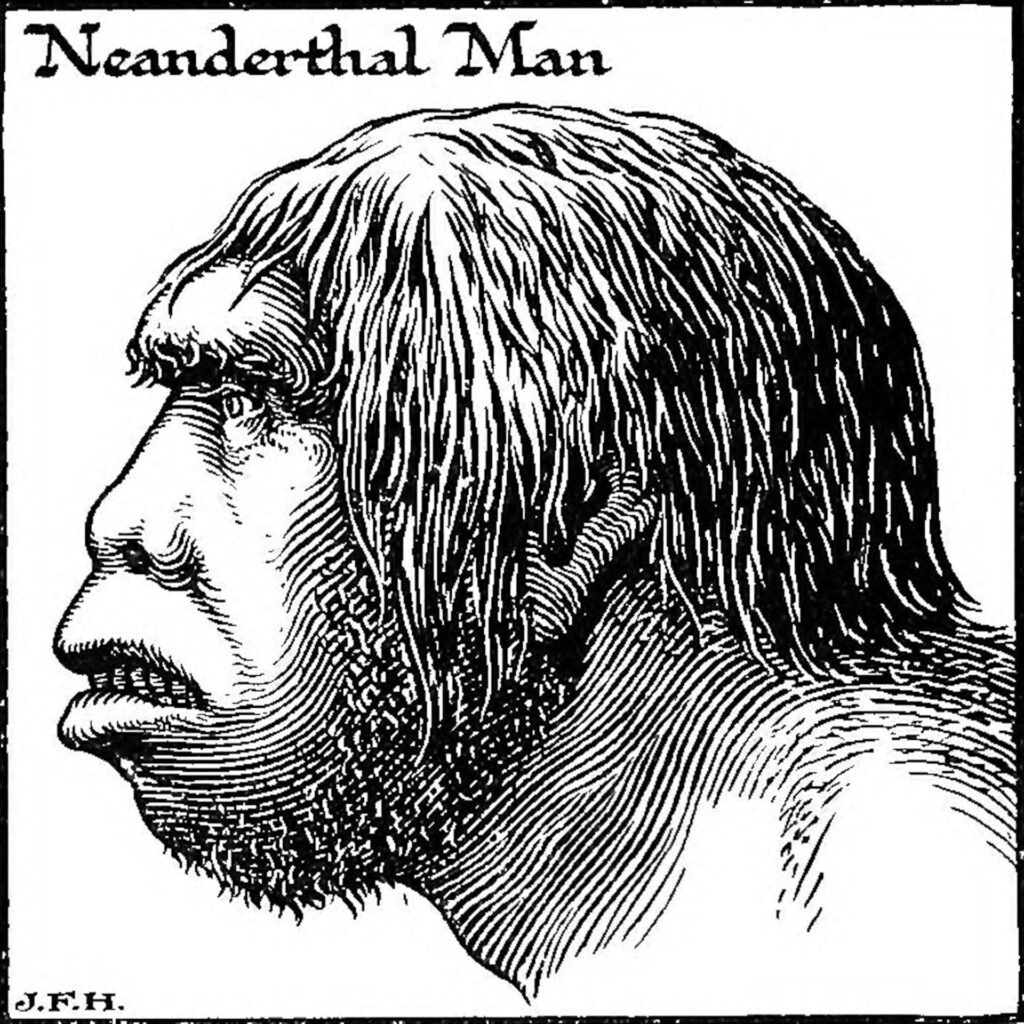

Appearing in H.G. Wells’ 1920 book The Outline of History: Being a Plain History of Life and Mankind, an illustration by J.F. Horrabin reinforced the perception of Neanderthals as violent creatures.

J.F. Horrabin/H.G. Wells/Wikimedia Commons

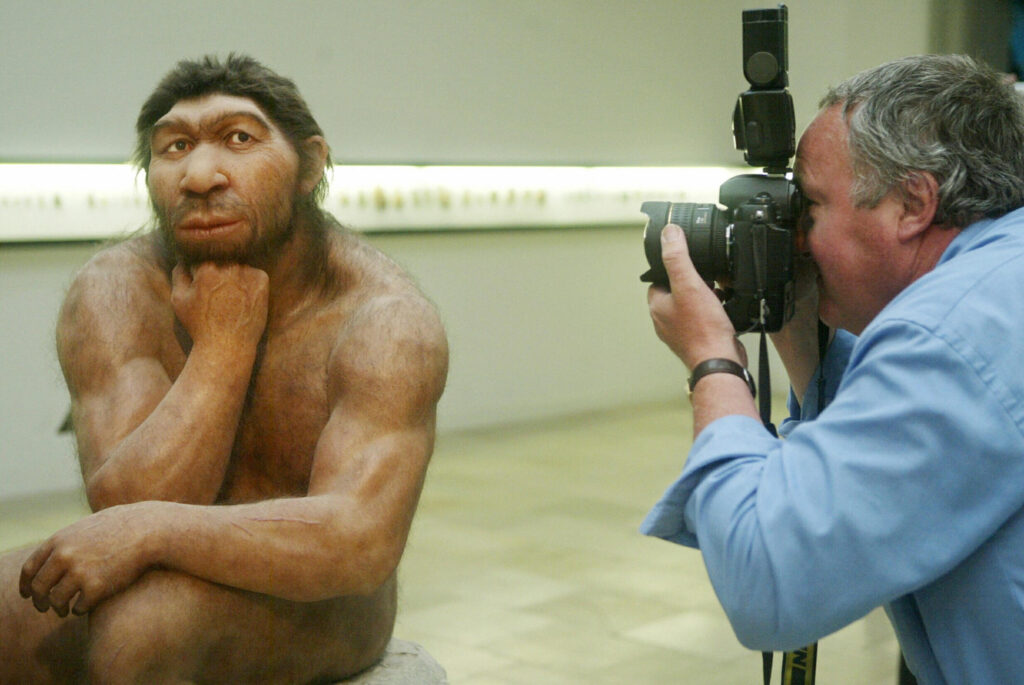

Thoughtful, smiling, and named “Mr. N.,” this contemporary reconstruction in Germany’s Neanderthal Museum is a far cry from the scowling Neanderthals visualized 100 years prior.

Neanderthal Museum, Mettmann/Wikimedia Commons

A present-day reconstruction of a male Neanderthal by Élisabeth Daynès stands at the Jeongok Prehistory Museum in Yeoncheon-gun, South Korea.

Elisabeth Haynes/Google Arts & Culture

In their 2008 depiction, Adrie and Alfons Kennis included information from ancient DNA studies that provided clues about Neanderthal eye, skin, and hair color.

Joe McNally/Getty Images

Similarly, a 1985 National Geographic illustration depicted Neanderthals communicating and cooperating while butchering an ibex and crafting tools. Notably, the females are the focus. They butcher, gather, and converse. Male Neanderthals, on the other hand, stand largely in the background.

The depiction of female Neanderthals as central characters challenged portrayals of Paleolithic women—usually shown tending infants on the periphery while men hunted and fashioned stone tools. Reflecting the Women’s Liberation Movement, this cartoon visualized feminist critiques of male-centric approaches to research.

NEANDERTHAL SUPREMACISTS

Still today, social and political forces bias interpretations of Neanderthals.

Contemporary depictions of Neanderthals at museums and in pop culture tend to have light skin as a result of genetics research in the early to mid-2000s. However, later studies examining more Neanderthal DNA concluded that at least some individuals had darker skin, brown eyes, and deep red hair.

How well can scientists glean skin tone from genomes? Another study considered both Neanderthals and well-known living people such as Henry Louis Gates Jr., a professor at Harvard University and the host of Finding Your Roots. Using gene markers, the authors predicted lighter or darker skin pigmentation with about 60 percent accuracy for the living folks—little over the random chance of a coin flip.

Still, the image of the “white” Neanderthal has persisted. White supremacists have latched onto the idea that harboring Neanderthal genes represents a marker of European purity—despite the fact that populations worldwide have traces of Neanderthal DNA, including, contrary to first reports, some African genomes.

Since their discovery, Neanderthals have occupied a precarious space as our uncanny cousins. Neanderthal images, rendered by researchers or artists, convey not only scientific hypotheses. They also express social movements and notions of humanness.

So, when looking at a Neanderthal image or any scientific illustration, consider what else it may depict: Science braided with sociopolitics.