Impossible Choices at the Crossroads of Motherhood and Fieldwork

Many women in science who must navigate motherhood and fieldwork will one day write an email like this:

Dear colleagues,

We have a big season ahead of us. We also have some happy news. I am pregnant. We will be starting the season as I begin my second trimester. We hope for the best, but we do want to make sure precautions are in place, should we need them. Can you advise us on the closest obstetrics clinic to the site and the name of a good doctor if you know of one?

I (Jamie) sent this message while preparing to do paleoanthropological fieldwork in a cave in northwestern Italy. Conducting fieldwork as a pregnant woman or new mother means planning for a complex set of situations, including potential miscarriage, pregnancy complications, breastfeeding, and child care. [1] [1] The use of the word “woman” or “women” in this essay includes trans women. In addition, many of the experiences of pregnancy and parenthood discussed in this essay are shared by some trans men and nonbinary people, though the prejudices and judgments individuals experience regarding parenthood in professional settings vary and may be different from those experienced by cisgender women. If we are fortunate to work in places with a strong health care system, that planning can be straightforward. If we are not, we might find ourselves writing another kind of message, as I (Jessica) did when embarking on fieldwork in Ethiopia:

I found out last Friday that I’m pregnant—welcome news, but bad timing for this trip. I’ve been madly doing research on what the major hazards would be for being pregnant in a malarial area. None of the doctors … can give me any decent advice. All they say is “Don’t go,” which to me is not an option.

Both of us wonder whether these challenges—which often leave women feeling isolated and unsupported—are discouraging them from entering a fieldwork-based career or becoming leaders of field-based projects. Along with the gender gap that plagues scientific publishing and grant applications, this could be limiting the diverse perspectives that are crucial to conducting the most innovative research. And as anthropologists who investigate the behaviors that allowed early humans to thrive, we recognize that the culture surrounding families in many professional settings runs directly contrary to how human societies evolved.

Our ancestors were able to spread across the Earth because we lived in cohesive groups that shared the responsibilities of breastfeeding and raising families. Reproduction and child care were at the core of their lives. Yet in many industrialized nations today, reproduction is seen as an inconvenience to our economic system and professional environment. This attitude is far removed from what made our species successful.

We believe there are ways to change this situation: to include more women and families in fieldwork, and to welcome the valuable perspective of mothers in scientific endeavors.

DIFFICULT DECISIONS ABOUT MOTHERHOOD AND FIELDWORK

Jessica’s story: I experienced the first glimpses of two of my babies while traveling for fieldwork. The first was an ultrasound during a pregnancy-related emergency hospital visit between flights to Ethiopia. The other was as a frowning doctor who said all was well but wrote a large, cautionary “40” at the top of the intake sheet after checking my age. As the field season progressed, more than one friend and colleague near that age had a heartbreaking pregnancy exam result. I wondered every day if I was next.

Female academics building a career feel keenly that two clocks tick simultaneously. Many find that their pre-tenure work and the most critical and vulnerable years of their career-building overlap with their biologically optimal reproductive years. Some may feel pressured to finish their degrees before starting a family. Others sense the urgency to gain tenure first. Still others feel cornered into not having children at all.

Being pregnant in graduate school and the early career phase can come with a lack of social and financial support, limited access to health care, and judgment about how seriously you take your profession. But people who bear children later in life increase their risk factors, and becoming pregnant can be more difficult and expensive, fundamentally changing long-held plans for how many children to have. There are no ideal options.

For those invested in disciplines involving extended fieldwork, deciding whether or when to have children is a weighty dilemma involving extra considerations: Can you interrupt fertility treatment, if needed, to do fieldwork? How might your health be impacted if you’re pregnant far from medical care? How might the recommended vaccines or disease prophylaxis for travel affect the health of your unborn baby?

The process of planning, experiencing, and recovering from a pregnancy takes, at bare minimum, more than a year. Breastfeeding can add additional years of care in which frequent mother-infant contact is essential. Developing a field project takes a similar time investment to conceptualize, establish connections, seek funding, and obtain permissions. Once brought to fruition, it often requires annual field seasons to maintain momentum.

So, it’s nearly impossible to hit “pause” on fieldwork for a year or to juggle project management with aspects of pregnancy and early motherhood that can’t be scheduled.

The authors are conducting a study on carer duties and career choices in the field sciences. If you are any person in the field sciences, with or without carer duties, and would like to participate in the study by completing a survey, please click here.

PREGNANCY AND CHILD CARE IN THE FIELD

Jessica’s story: Weeks before the field season was set to begin in a remote desert area of Ethiopia, I packed and repacked my clothing and supplies, trying to get it all to fit. But I was going in my first trimester, and there was an extra possibility of miscarriage. I needed a lot of pads to potentially deal with blood loss, which can last for two weeks. I removed an extra pair of field pants, noting that no man ever had to make that decision.

After I arrived, a complication did arise, and I needed medical advice. I climbed a large outcrop and waved my phone in the air at a particular time in the evening to get a signal. I was then able to text my partner so he could check with a nurse. If I was lucky, I might have a reply the next evening when I tried again.

Being pregnant in the field comes with a load of precautions, responsibilities, and concerns. Once your child is born, another set of dilemmas arises. Will you have to stop breastfeeding early to conduct fieldwork? As your children grow, will they—or you—suffer a lasting emotional toll because of your extended absences and lack of communication options if you can’t bring them with you? If you do bring your children, how can you ensure their safety and emotional well-being? Will it compromise your ability to do the job? And how can you possibly afford it?

“My perspective as a pregnant woman and mother brought detail to the past and allowed for a more informed and deeper interpretation of our findings.”

Jessica’s story: My son was 1 1/2 years old when I first left him to embark on my first project as a field director. We were at the airport, and he was in a stroller with my parents, who would care for him while I was working in Malawi. I wouldn’t have network connection there. And can you even call a 1 1/2-year-old? How do you let him know his mother is thinking of him? I fell onto my knees and embraced the stroller with him in it, because I knew if I picked him up and he struggled to go back into the stroller, I wouldn’t have been able to bear leaving him.

That moment was a crossroads in my career: Would I be able to leave him and be a field director or not? Later my ex-husband argued to a court that I had abandoned my son to do this research necessary for my job. But how many men leave their kids with wives or grandparents to travel for work?

Intergenerational and extended family care is practiced in cultures around the world. But in many countries that fund the majority of field research, mothers are typically not routinely supported by a large family group or community. In some of these places, community-derived and shared child care—which is common in many traditional societies—is nonexistent, while private child care and child care centers are extremely expensive, and most workplaces and professional meetings do not offer child care. Few research-granting agencies allow primary investigators to request funds for child care or family travel. Single-parent families feel this burden especially keenly.

Any family with working parents understands the crushing tension between being able to do your job and having the fortitude and financial ability to leave your child in the care of others. While this affects all genders of parents, women carry the weight of child-rearing in different ways. Biological constraints such as pregnancy and breastfeeding further complicate what is already a more fraught social landscape for female-identifying people. Speaking about these constraints may be discouraged in the workplace, silencing those who want to advocate for the care they need to continue doing their jobs well.

Jamie’s story: I began the field season in Italy at the beginning of my second trimester. I wanted to run the season the way I always had, hiking to the site in the morning and returning to the lab in the afternoon. That season the hike made me feel awful. Despite having strong collaborators and my husband to support me, I didn’t know how to talk about the physiological toll I was feeling. Some people run marathons while pregnant. Was I just terrible at being pregnant? Everyone was working so hard that I felt some guilt, and I knew no one could really understand what I meant when I said, “I feel wiped out by the hike. My head feels heavy, and I feel disoriented.” Nevertheless, I shifted to working in the lab and visiting the cave once a week.

The next season when we brought our daughter, I resumed hiking to the cave most mornings, then hiked back down and drove to the house to breastfeed, then to the lab, then back to breastfeed. My baby was young enough to require round-the-clock care. I was fortunate that my mother-in-law was willing to travel with us to provide the necessary support. We used money we had been saving to cover the costs—something a single-income family could not do.

All of these burdens can lead to an imbalance in the opportunities women have to become leaders in their arena. Many women—especially those who plan to become pregnant and potentially breastfeed—may consider field-oriented jobs to be more out of reach than lab-based research, leading to further gender disparities. But excluding childbearing people from fieldwork seems irrational when viewed through the lens of human history.

Read more from the perspective of an anthropologist who grew up traveling to field sites with her anthropologist parents: “The Gift of a Bicultural Upbringing.”

CONTRIBUTIONS OF MOTHERS AND COMMUNITIES, THEN AND NOW

Jessica’s story: My husband and I planned to bring both our kids to our fieldwork in Malawi. Since we had been trying for another child, my husband suggested, “Maybe we’ll bring all three!” In the end, we did. We had our first ultrasound during the mid-season break and saw the tiny legs drawn up to the chest. For the first time in my career, I also discovered a human burial: an infant, legs curled up in the same position as my baby’s. Later, using ancient DNA for one and DNA extracted from my blood for the other, we found out both babies were boys.

The experience of becoming a mother while studying human evolution has been revelatory to me (Jessica). That fundamental and near-universal human experience of having children and being around children—which is an important part of my research on ancient societies—was entirely alien to me until I had children. It’s the hands-on experience of living your research in a way you can’t model in a lab.

Having children showed me how much work it is just to keep them safe and alive, and how constantly they face challenges as they learn to walk, use tools and language, and understand symbolism—connections our ancestors once had to make for the first time.

Archaeologists are in a quest to learn about past people’s lives, which we must reconstruct from fragments. Any personal detail—like the parallel between a buried baby and an ultrasound image—reaches across time and makes you realize you are touching another human life. When that happened, I began thinking a lot more about the circumstances of this baby’s passing and burial. What did the child mean to their society? How did this happen, in this exact spot, so long ago? How did his mother cope with the loss?

Before becoming a mother, I would have asked those questions much more academically and clinically. After becoming a mother, I felt those moments because I could imagine them more vividly. This insight has led me to consider research questions I may not have considered before, and given me a perspective on the lives of others that makes me a better mentor to my students.

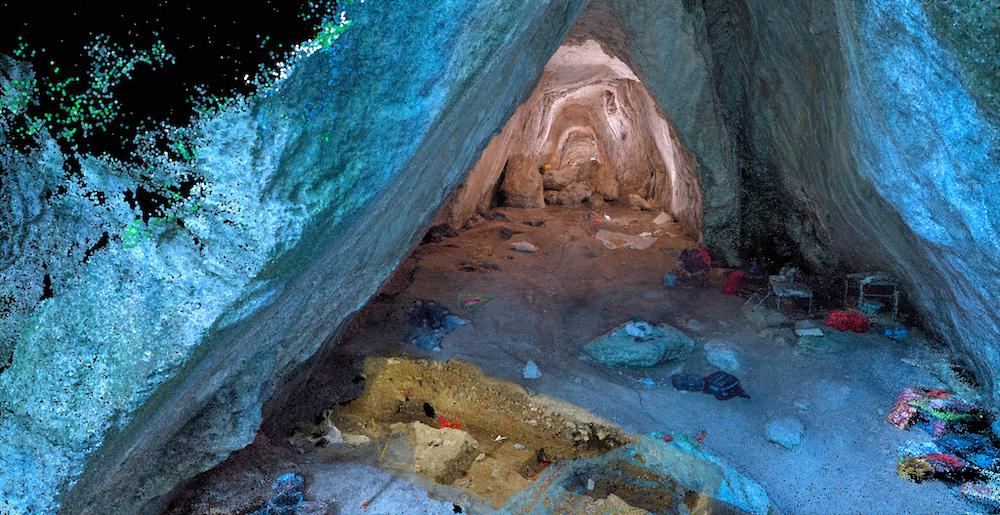

Jamie’s story: I was pregnant when my team uncovered the top of a human infant skull in the Arma Veirana Cave in Italy. Because it was the last day of the excavation, we had to cover the burial with a protective layer and wait until the following season to unearth it. When we returned, my husband and I brought our 6-month-old daughter. As we excavated the remains, we discovered the body, and later learned she was a baby girl, just a few months younger than my own. Our team named the ancient child “Neve.”

Though they were born 10,000 years apart, Neve and my daughter are intimately connected in my mind, having emerged in my life at nearly the same time. As I recovered Neve’s tiny bones, I cried, understanding some of her mother’s pain, since I had experienced a miscarriage not long before.

As one of the project directors of the Arma Veirana dig, my perspective and presence as a pregnant woman and mother brought detail to the past and allowed for a more informed and deeper interpretation of our findings. In fact, I am proud we were able to tell a small part of the story of the infant’s mother. Isotopes from the infant’s teeth revealed clues about the mother’s eating habits, and stress lines in the baby’s teeth suggested the mother endured stress during her pregnancy.

After finding Neve and having my daughter, I will never see the widespread movement away from hunter-gatherer life in the same way. Work like this can provide details about the experiences of females in the past.

The perspectives of women, mothers, and people from diverse backgrounds and gender identities benefit field projects. But inclusivity can be hard to achieve in professional cultures that assume parents can or should leave their children at home when participating in field projects. It is also difficult to accomplish under institutions that consider the costs of child care and family travel to fall outside the purview of the scientific endeavor. It is ironic to devote a professional life to understanding the economic aspects central to the evolution of human societies—including gestation, lactation, and child care—while pretending we are somehow exempt from these same conditions.

One of the most fascinating puzzles in human evolution is how dependent humans have been on alloparenting—aid from other community members in raising children. Some anthropologists have proposed this is why humans have such long lifespans, since grandparents contribute to the ongoing well-being of the family.

As both anthropologists and mothers, the image that emerges for us from the archaeological record is that ancient hunter-gatherers appear to have thrived, living in groups and taking care of their communities. The way many people in industrialized societies live today seems so unnatural, so removed from how we evolved.

MORE INCLUSIVE SOLUTIONS FOR FAMILIES

So, let us imagine a different way to bridge motherhood and fieldwork in societies where this gap exists—a way that situates women, children, and families within the research mission. Let us view scientists as whole people who are parts of families and communities, not isolated in their careers. Then let’s reconstruct the duty of institutions and granting agencies to provide support for the whole scientific endeavor.

Consider a scenario in which any field researcher with grant money can apply for a special fund to bring a health care worker onto their team. Perhaps early career or retired nurses or doctors would find value in spending a few months with research teams—with travel, room, and board provided—to work in places that capture so much public interest. Funding for this would support a whole team. Pregnant people and individuals who feel excluded because of health conditions would no longer need to feel so alone or afraid.

This reframes at least part of the issue as an economic problem, solvable via economic means. But we must also collectively flip the script and consider the benefits we all gain in field science by making mothers feel included. When a woman informs colleagues she is pregnant, the small voice that responds, “She’s not serious about the work,” or, “This is a problem” should be replaced with the sense that something new and exciting has been added to the way the research can unfold.

We need the immediate reaction to be: “How can we best support this?”

Brilliant early career field scientists are currently making impossible and often hidden decisions that will shape the next generation of research. It is time to talk about this issue, and to fix it. Normalizing “women’s issues” so they become “community issues” and offering equitable access to health care, family travel, and child care for people traveling for fieldwork would be revolutionary moves toward diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Using funds to support the humanity of scientists would allow them to concentrate fully on their mission, and it would broaden the diversity of perspectives in research. By bringing the process of motherhood and fieldwork back to our human roots, we can make the science both better and more relatable to the world.