Raiding Graves—Not to Rob but to Remember

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

From the collapse of Roman power to the spread of Christianity, most of what we know about the lives of people across Europe comes from traces of their deaths. This is because written sources are limited, and in many areas, archaeologists have only found a few farmsteads and villages. But thousands of grave fields have been excavated, adding up to tens of thousands of burials.

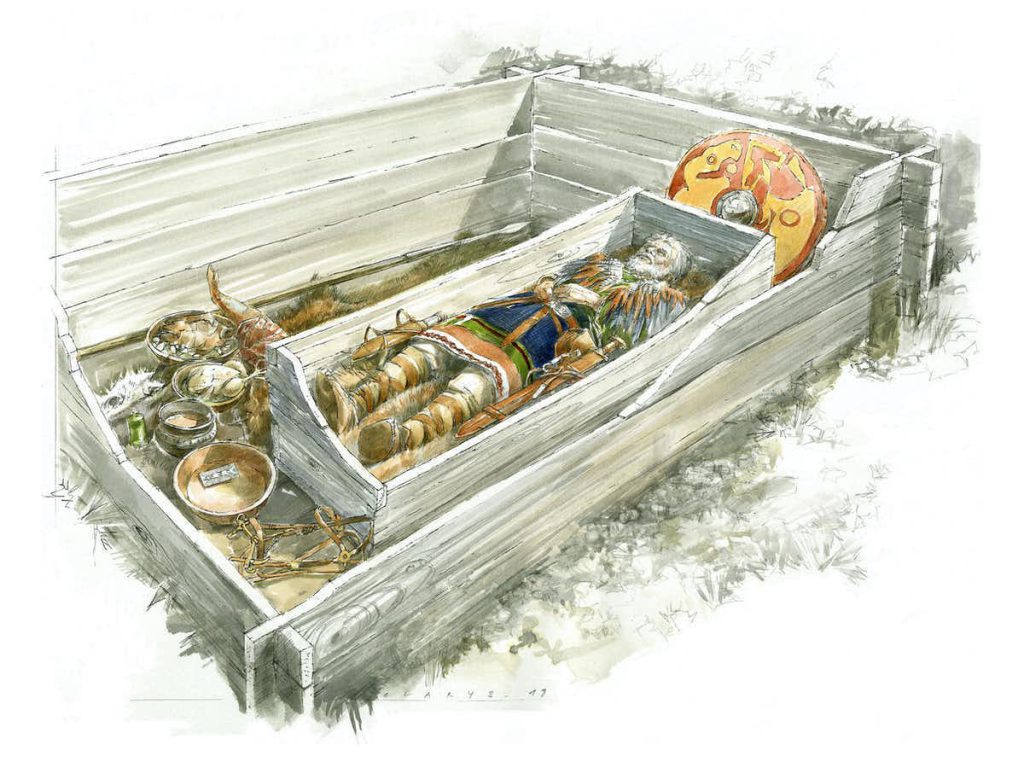

Buried along with the human remains, traces of costumes and often possessions, including knives, swords, shields, spears, and ornate brooches of bronze and silver, have been found by archaeologists. There are glass beads strung as necklaces, as well as glass and ceramic vessels. From time to time, they even find wooden boxes, buckets, chairs, and beds.

Yet since the investigations of these cemeteries began in the 19th century, archaeologists have recognized that they have not always been the first to reenter the tombs. At least a few graves in most cemeteries are found in a disturbed state, their contents jumbled and valuables missing. Sometimes this happened before the buried bodies were fully decomposed. In some areas, whole cemeteries are found in this state.

The disturbance has been termed grave robbery and lamented as a loss for archaeology in the removal of hoped-for finds and data. For example, the digger’s reaction to the discovery of one disturbed burial recorded in excavation notes in Kent, England, in the 1970s is typical: “The big event—and disappointment of the day.”

But our research shows that robbing is not the right label for what happened to these graves—in fact, something else was going on.

DISAPPOINTING DISCOVERIES

Our new research has reexamined evidence from sites in different areas of Europe and shown that the grave disturbance phenomenon is far more widespread than previously recognized. From Transylvania to Southeast England, communities started to adopt customs of reentering burials and removing certain objects in the later sixth century. The practices peaked in the early seventh century.

In some areas, frequent discoveries of ransacked graves created an image of pillage and violation of the dead, which came to be seen as typical of the post-Roman power vacuum across Europe. In some cases, the violations were not even attributed to strangers: Earlier 20th-century French archaeologists believed that reopened graves reflected the barbaric nature of the Germanic tribes then thought to have used the cemeteries and to have robbed their own relatives.

However, over the decades, many excavators in different countries pointed out that there were signs that this was not straightforward robbery. For one thing, it was highly selective, with particular objects taken and others left behind—sometimes even gold coins.

Such observations were not connected, because the discussions were mainly only of single cemeteries and divided by language barriers, so no one could see the extent of the evidence.

In our research, we collected and reassessed thousands of records of disturbed burials in several countries to understand when graves were reentered and what exactly was done to their contents. We show that the reopening practices have similarities across Europe, especially the careful selection of artifacts.

In one case in Southern England, a complete necklace with 78 beads and six pendants, variously of silver, silver-gilt, glass, and garnet, was no longer lying around the neck of the deceased, and all the remains had been moved about. The necklace seemed to have been lifted and moved but still left in the grave.

In many tombs, we can tell other objects had been removed since metal staining, rust marks, and few fragments of these objects were left in the graves. Such residues suggest that these items were in poor condition when they were taken, as these are signs that the materials had degraded. The level of such metal staining, rust staining, and fragments present suggest that the items were in such a degraded state that it was unlikely they could have been used or exchanged.

CONNECTION THROUGH BELONGINGS

Swords and brooches are most consistently missing from disturbed burials across Europe. The choice of swords and brooches, out of all the valuables left with the dead, seems to be related to their roles as heirlooms—possessions used to connect people across generations.

Typically, we found that bones and objects were moved around within coffins that had not broken down yet. This suggests that reopening happened after a few years had passed, even when the soft tissue holding together skeletons had rotted. More recent graves were mainly chosen, even though older burials in the same cemeteries were usually much richer. This would suggest that theft of valuable items was not the intention of opening the graves. Rather, the aim was to retrieve special belongings with close connections to remembered individuals and their families.

We know from archaeological and ethnographic records all over the world that it is common for people to revisit the remains of their relatives, sometimes transferring them to new resting places—and famously in Madagascar, even dancing with decomposing corpses. The customs in early medieval Europe are unusual since they focus on belongings rather than bodies. But they show how laden with meaning and emotion the possessions placed with the dead were in how people thought about life and its end.