When Life Imitates Art in Ukraine

On February 24, 2022, the Russian Federation invaded Ukraine. Counter to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s apparent intentions, the Russian army did not achieve quick victory. Ukrainian wherewithal, fortitude, and bravery, and a great deal of outside support, have instead ushered a surprising string of Russian defeats. As the invasion’s first anniversary approaches, it seems increasingly likely that combatants are facing a long and bloody stalemate.

Almost a month later, on March 17, coverage of the war struck me, in the comfort of my Denver home, in an unexpected way. That day, major Western media outlets covered the funeral of Ukrainian Officer Ivan Skrypnyk, who was killed during an airstrike on the Yavoriv military complex in western Ukraine, near the Polish border. U.S. news outlets flashed photographs of Skrypnyk’s grieving mother, draped over his casket.

I felt a strong shiver of déjà vu. I’d seen a similarly bereaved mother before, but not in photographs. Her earlier apparition was carved in gemstones.

To explain my déjà vu, I need to share my research on Soviet artist and gem carver Vasily Konovalenko (1929–1989), whose work I have been studying for more than a decade. The Denver Museum of Nature & Science, where I work, has on display 20 Konovalenko gem carvings. They depict classic scenes in Russian and Ukrainian folk life, all uniquely shaped out of malachite, amethyst, jade, obsidian, jasper, quartz, and a host of other gemstones. Reminiscent of sculptures from the workshop of the great Peter Carl Fabergé (creator of Fabergé eggs), Konovalenko gem carvings stand unrivaled in their dynamism, their use of color and texture, and their evocative whimsy and passion.

In 2016, I published Stories in Stone, the first and only comprehensive English-language book on Konovalenko and his work. While conducting research for the book, I had the pleasure of traveling several times to Moscow and St. Petersburg to examine and photograph Konovalenko’s remarkable sculptures, which have been kept in museums and repositories for national treasures.

One museum, Muzey Samotsvety, or the State Gems Museum, holds an exquisite collection of Konovalenko gem carvings—20 on public display and four more in storage. Located on a major throughfare in Moscow, the museum constitutes the first floor of a nondescript Soviet-era apartment. From the drab façade, you might expect the space to house a poorly funded CrossFit gym or a community meeting space. Inside, the objects and specimens sit in dark casework, and the carpet sorely needs replacement. The lackluster space hardly befits the wondrous objects curated there.

Konovalenko carved the sculptures on display at Samotsvety between 1956 and 1981, spanning across his career. Like the Denver pieces, most of the Samotsvety gem carvings depict pleasant scenes of people chatting, having tea, foraging mushrooms, fishing, and otherwise enjoying themselves. One sculpture, however, is sullen, morose, and deliberately unenjoyable. Until last March, it was also one of my favorite Konovalenko gem carvings.

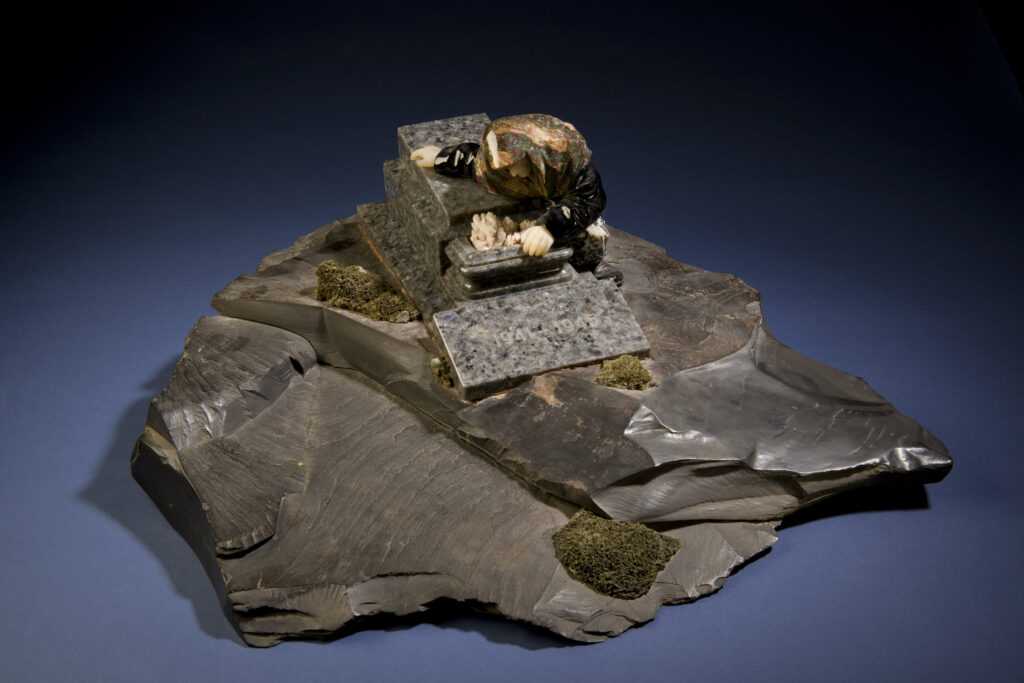

The sculpture, Bereaved Mother, portrays a woman huddled over a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, which in this case honors Soviet soldiers from World War II. The woman and tomb lie on an austere gray-black slate base that is oversized relative to mother and monument. When viewed from above, the hefty slate slab draws in and fixates our attention on the sculpture’s central scene.

A close-up of the mother and tomb reveals Konovalenko’s gem-carving genius, including his ability to select and carve diverse raw materials. The various mineral properties of the chosen gemstones infuse his work with texture, color, and vibrancy.

Chiseled from mottled jasper, her brightly colored shawl pays silent homage to Pavlosky Posad, a traditional center of colorful Russian folk textiles located two hours’ drive east of Moscow. A single piece of obsidian, or volcanic glass, forms her black coat, which Konovalenko has deftly carved to create the appearance of fabric folds at her elbows. Ghostly white calcite renders her ashen face and feeble hands. A small flaw in the calcite, not visible in most photographs, resembles a tear falling from her left eye, just above the cheekbone. On the tomb, raw, unpolished calcite looks like snow and ice, adding a sense of chill to the discomforting scene. Small epodite bushes grown opportunistically from crevices in the foundation.

According to Konovalenko’s widow, whom I’ve interviewed formally and come to know quite well over the years, the artist crafted Bereaved Mother sometime between 1973 and 1981 while working at Samotsvety; exhibit labels at the museum do not provide a conclusive date. She recalls that Communist Party officials ordered him to carve it for Victory Day, which occurs annually on May 9 and commemorates the Soviet victory against Nazi Germany.

Note the sculpture’s tomb bears the dates “1941–1945,” leading to confusion about what’s being represented. The Soviet Union entered World War II in 1939. The 1941 date may instead refer to the surprise attack Nazi Germany launched against the Soviet Union, which changed the war’s trajectory and led to tremendous hardship for Soviet soldiers and citizens. Whatever the case, Bereaved Mother alludes to massive Soviet sacrifice during the war years, when more than 20 million of the nation’s people died.

I used to like Bereaved Mother. With its somber subject, the piece stands apart from the cheery, theatrical nature that most of Konovalenko’s sculptures embody. Unfortunately, as Oscar Wilde wrote in 1889, “Life imitates art.” The photograph of Officer Skrypnyk’s mother grieving over his casket looks as if it were modeled after Konovalenko’s sculpture, and vice versa.

My oldest son is now 19, old enough to be fighting wars. As the war on Ukraine continues, and unnecessary casualties mount, thousands upon thousands more mothers, fathers, spouses, children, and friends will become bereaved. Joseph Stalin allegedly once said, “The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of millions is a statistic.” He was right in the first instance and pathologically wrong in the second.

To my eyes, Konovalenko’s Bereaved Mother is no longer merely masterful art. It now depicts a tragic reality unfolding because of Russia’s war on Ukraine. The scene is too personal, poignant, and common, even for an American scholar living half a world away.