What a Cow’s Horn Reveals About Khoisan Medicine

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished with Creative Commons.

A SURPRISE INSIGHT INTO KHOISAN MEDICINE

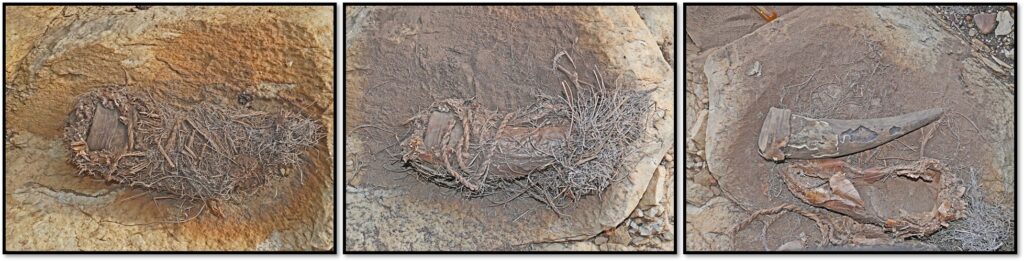

In 2020, a chance discovery near the small South African hamlet of Misgund in the Eastern Cape unearthed an unusual parcel—a gift to science. The parcel turned out to be a 500-year-old cow horn, capped with a leather lid and carefully wrapped in grass and the leafy scales of a Bushman poison bulb (Boophane disticha). Inside the horn were the solidified remnants of a once-liquid substance.

Thanks to chemical analyses, we now know that the horn was a medicine container. It is the earliest-known object of its kind from anywhere in Southern Africa and offers the first insights into precolonial medicines in this part of the world.

My colleagues and I conducted chemical analyses of the contents. We identified several secondary plant metabolites, the most abundant of which were mono-methyl inositol and lupeol. Both of these compounds, and indeed all of those identified, have known medicinal properties.

This remarkable find is the oldest example in Southern Africa, of which we are aware, of two or more plant ingredients being purposefully combined into a container to form a medicinal recipe. Several museums in South Africa house examples of medicine horns collected during the 19th and 20th centuries—but none has ever been found in an archaeological context.

VARIOUS PLANT USES

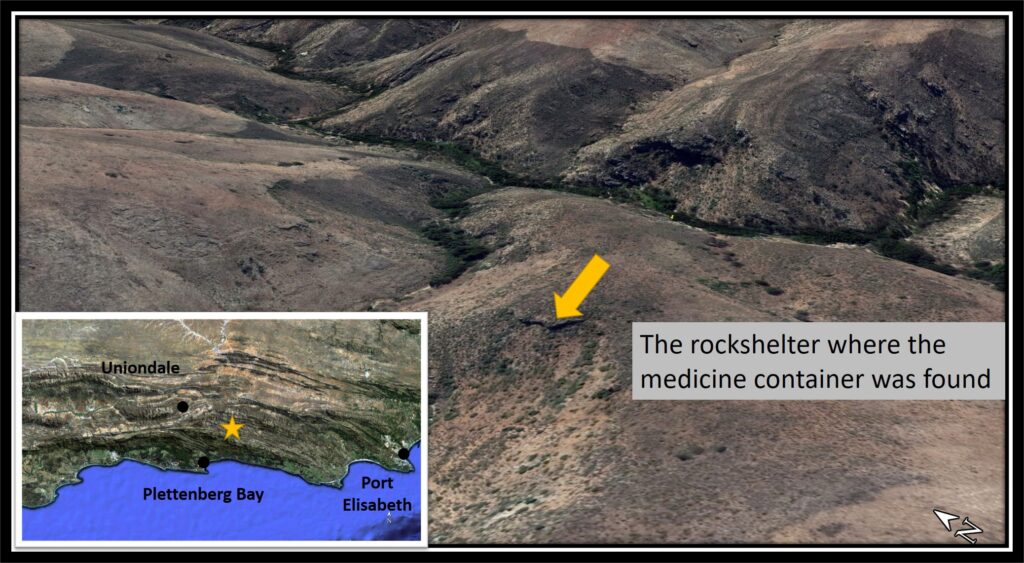

The medicine container was found in a painted rock shelter. A radiocarbon date of the horn container places the parcel at around A.D. 1461–1630. Although the rock shelter contains several San paintings, we do not know if they are the same age as the horn container. At this time, the area was occupied by both San hunter-gatherers and Khoi pastoralists. Both believed in a mythical animal, resembling a domestic cow, whose horns were considered to have medicinal attributes.

People have exploited the pharmacological properties of plants for at least the last 200,000 years. During the Middle Stone Age (which started about 300,000 years ago and ended between 50,000 and 20,000 years ago), people burnt certain aromatic leaves to fumigate their sleeping areas. Plant extracts also seem to have been the main component of glues and adhesives and hunting poisons around this time.

But not much is known about traditional medicines from the precolonial era of Southern Africa. What information there is derives mainly from early traveler accounts and modern ethnographic studies. The horn offered us a chance to learn a little more about the Traditional Knowledge of medicine and pharmacology during this early period.

The descendants of these communities still live in Southern Africa today.

MEDICAL AND SPIRITUAL APPLICATIONS

The main compounds present in the container, mono-methyl inositol and lupeol, are still found today in a variety of known medicinal plants in the Eastern Cape. They have a wide range of recorded medicinal applications, including the control of blood sugar and cholesterol levels, and treatment of fevers, inflammation, and urinary tract infections. They can also be applied topically to treat infections—rubbing ointment into cuts in the skin is one of the ways the San are known to have administered certain medicines.

Both mono-methyl inositol and lupeol are pharmacologically safe compounds. This means that they can be ingested without the risk of overdose. Both compounds stimulate the production of dopamine in the brain; mono-methyl inositol is used to treat anxiety, and plants containing lupeol are used as aphrodisiacs.

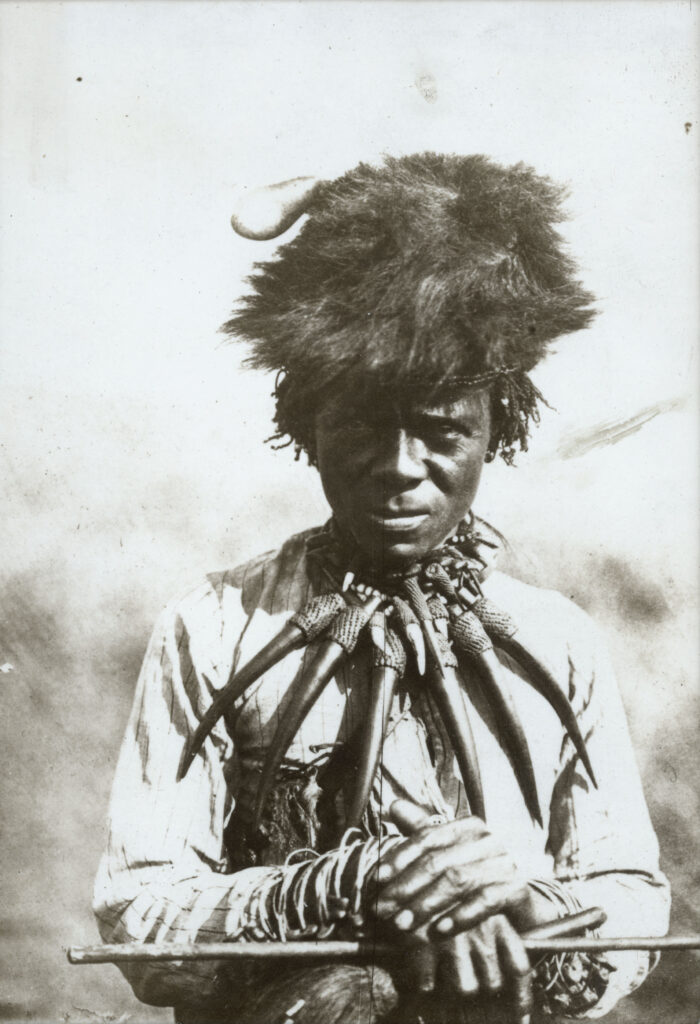

For the Khoi and San people, not all medicines were meant to treat physiological illnesses. Healers were specialized individuals whose task was to treat both physical and spiritual ailments. Indeed, one of the principal functions of traditional medicine, both in the past and today, is to treat supernatural bewitchment. Medicine and culture remain intimately entwined and traditional medicine, which is highly adaptive, continues to play an important role in much of Africa as a primary health service.

A TREASURED POSSESSION

We cannot know exactly what the medicine stored in the horn was used for, how it was administered or who precisely used it. But it was clearly a treasured possession, judging by the way it was carefully wrapped and deposited in the rock shelter. Its owner evidently intended to retrieve it but never returned.

The absence of any evidence of long-term occupation of the shelter means that the medicine horn is an isolated, chance discovery. Nevertheless, this is a find that sheds new light on traditional medicines used in the Eastern Cape 500 years ago.