Archaeological Tropes That Perpetuate Colonialism

Empty lands. Abandoned. Up for grabs.

That’s the logical—but mythical and false—thinking of settler colonialism, or the replacement of one set of peoples with another, in what is today the United States. The idea that Indigenous peoples had previously “abandoned” their lands meant those places could be occupied by settlers. The lands could then be mined, “scientifically” excavated, made into federally run parks or forests, or otherwise used at will by the U.S. government.

Starting in the 19th century, archaeologists helped create a recurrent theme, or trope, about social collapse and abandonment that was figurative and metaphorical, not literal or based in Indigenous truths. As Indigenous archaeologists ourselves from Tribal communities in the U.S. Southwest—Laluk is Ndee (White Mountain Apache), and Aguilar is San Ildefonso Pueblo (Tewa)—we’re all too familiar with how these tropes still carry weight. These narratives implicate archaeology in the dispossession of Indigenous peoples from our lands, resources, cultural patrimony, and histories. Ultimately, some of the ideas that come from archaeology have been used to justify the basic practices of settler colonialism.

The dispossession of Indigenous peoples from our lands is much more complicated, of course. Nonetheless, one of the real-world consequences of this mindset for contemporary Indigenous peoples is that we have few legal rights to have a voice in the care and disposition of much of our ancestral lands and places. These landscapes are still vulnerable to the tendencies of settler colonialism.

We confront these mindsets by offering new perspectives on archaeology informed by Indigenous ways of thinking that can begin to rewrite the narrative and shift theories and methods within archaeology and beyond.

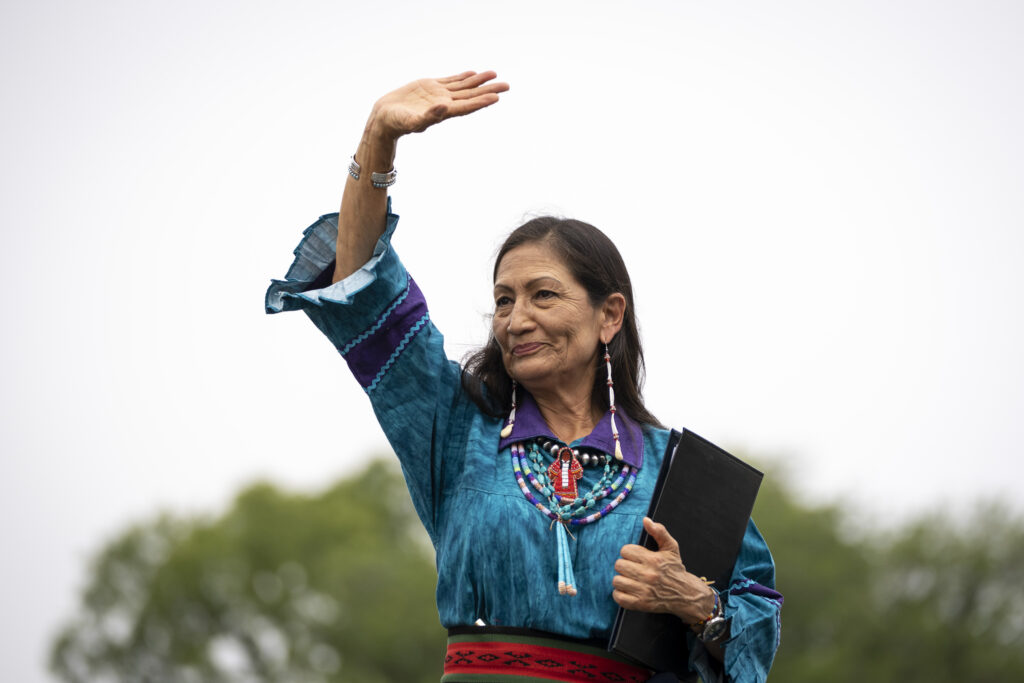

Today, with the appointment of Secretary Deborah Haaland, a member of Laguna Pueblo (a federally recognized tribe), as head of the U.S. Department of the Interior, the stories and laws might be changing within certain contexts. However, false interpretations of history still perpetuate the harms of colonialist practices. These flawed chronicles undermine Indigenous peoples’ knowledge about their own histories on specific landscapes. They also continue the erasure and misrepresentation of American Indian pasts in public narratives.

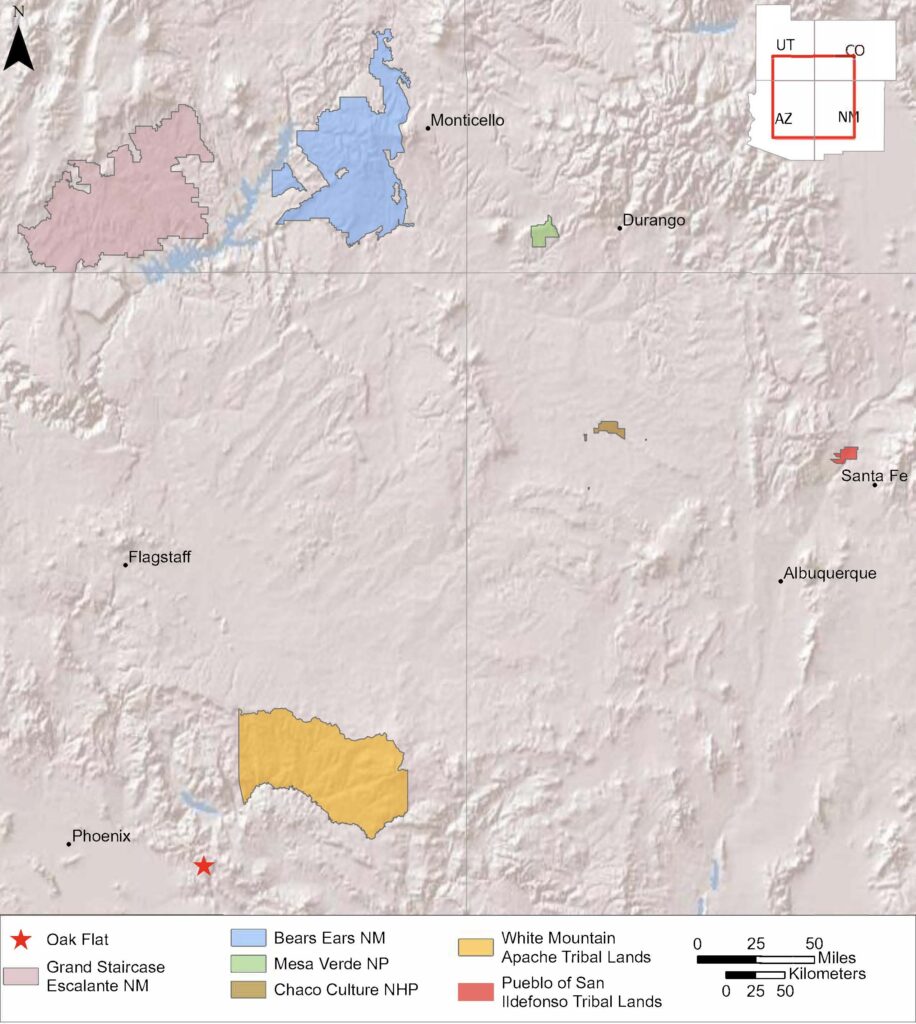

Yet with the increasing presence of Indigenous people in positions of leadership and within archaeology, issues and places that are important to Indigenous communities are being elevated. They can no longer be ignored. For example, U.S. President Joseph Biden recently approved a 20-year ban on oil and gas drilling in Chaco Canyon and surrounding areas in northwestern New Mexico. In 2021, he restored the boundaries of Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments in southern Utah.

But many more places are at risk. Chi Ch’il Biłdagoteel, or Oak Flat, in Arizona, continues to be threatened by exploitation and desecration by the international mining company Resolution Copper.

Many protective actions are a result of the advocacy of Indigenous people and the reassertions of Original claims and affiliations to these places. This is not a reversal of the past harms inflicted on these areas by any means. But these protections have certainly elevated the discourse surrounding these places in particular and Indigenous ancestral lands and places more generally.

To further elevate the discourse, we suggest that public views—and those within Southwest archaeology more specifically, where we live and work—need to shift the focus from abandonment to persistence. We need to start with presence rather than absence. How did Indigenous communities survive, persist, and come to live at the places where they are today? How do Indigenous people conceptualize and engage with the places of their Ancestors? What stories do they share with their grandchildren?

Through a critique of the misaligned views of archaeological thought and practice, and by centering Indigenous communities’ knowledge and practices, we can begin to move toward a more complete telling of the past. Such a narrative resituates Indigenous peoples with and within our ancestral places, which is critical to our survivance.

In archaeological contexts, the term abandonment has often been used to mean the absolute desertion of places. Following this view, people are thought to abandon a place when their cultural systems fail to adapt to the local environment, causing a “collapse” during which residents migrate without any intention of returning.

This view fails to consider Indigenous conceptions of movement and perceptions of place. Viewed from an Indigenous perspective, abandonment is a fallacy and overlooks the nuanced ways in which Indigenous peoples maintain relationships with their landscapes.

For example, archaeologists have asserted that people abandoned Chaco Canyon, located in modern-day New Mexico, in A.D. 1150 due to environmental stress and social strife. In the well-known cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde to the north, the desertion supposedly occurred around A.D. 1300 for similar reasons.

But from the viewpoint of the descendants of Ancestral Pueblo People, people moved. Such movement from one place to the next was common and, in some cases, a spiritually preordained process. In the case of Pueblo People, they traveled to different areas seeking their middle place. This is the center of their particular communities’ physical home on the cosmological landscape. Far from having abandoned Chaco or Mesa Verde, Pueblo Ancestors made the choice to keep moving. But future communities stayed connected to those places both literally (through pilgrimages) and conceptually (through prayers and Oral Traditions).

The archaeological myths about collapse and abandonment deny how contemporary Indigenous peoples maintain continuity or association with ancestral places. Such concepts have been and continue to be part of a broader project of naming and categorizing that Western interests have used to exert power and control resources.

As the archaeologist David Hurst Thomas wrote, “The power to name reflect[s] an underlying power to control the land, its Indigenous people, and its history.” Archaeologist and Choctaw Indian Joe Watkins explains that although “American Indian tribes have separate status as sovereign nations, the control of heritage and cultural property extends only to lands owned by the tribe or the U.S. government.”

So, after hundreds of years, the question remains: Who controls the narrative?

Western perceptions within archaeology continue to control the narrative about Indigenous people—dominating methods, theory, and practice. Efforts to decolonize and Indigenize archaeology are being made. However, the structural components of past Western dominance remain deeply embedded in both the discipline and how a broader public understands Indigenous histories.

To shift the current popular narrative, we aim to create Tribally driven, community-based research. In our work, we ask: How do the communities themselves who have direct and ongoing ties to the areas/places archaeologists are interpreting and speculating on define what their Ancestors did there? How do we foreground Indigenous knowledge and cultural resources best management practices as primary interpretive and methodological tools?

We also ask the bigger question: Is archaeology trying to force us to abandon ourselves?

Between the two of us, we are in frequent dialogue about the structural and systemic issues of archaeology as a discipline. Our discussions often focus on our positionality—meaning, our status and relationship to others as Indigenous scholars—as some of the few Indigenous students to have gone through anthropology graduate programs. Other conversations center on being viewed by non-Indigenous archaeologists as the sole “experts” on our own cultures.

This collective introspection has led to a healthy critique of the discipline from our own standpoints. We have worked to tease out the embedded stereotypical and paternalistic understandings about Indigenous communities that we confront on a daily basis.

For example, as an archaeologist working within and adjacent to my (Aguilar) own community of San Ildefonso Pueblo, a Tewa-speaking community in New Mexico, I regularly witness how outside archaeologists have a skewed perception of Pueblo pasts and presents. This is because their archaeological training and practice have largely been devoid of Pueblo perspectives. Conversely, my community has a justifiably skeptical view of archaeology that is grounded in a legacy of extractive practices. I continually work to remedy the legacy of archaeology in my community while asserting Native sensibilities into the discipline at large.

Meanwhile, archaeologists such as Stephen Lekson and Catherine Cameron have brought a deeper awareness to these myths and the powerful narrative behind them. They argue that the word “abandonment” is inaccurate to describe how people moved into and out of Chaco Canyon in the past. The term is further inappropriate for both Chaco and Mesa Verde in the present. “Ancient Pueblo places—buildings and villages archaeologically abandoned—continue to influence the lives of Pueblo people,” they emphasize.

Yet as more scholars appreciate the complexity of cultural and historical processes, many continue to ignore the long-standing ties and use-histories that link ancestral sites with contemporary communities, say archaeologists Chip Colwell and T.J. Ferguson. This disregard is critical to unveil because the idea that Indigenous peoples left behind their ancestral places, with no plan to return, persists in news articles, magazines, and educational materials that continue to shape public perceptions.

Only through valuing other knowledge-making systems can scholars and the general public begin to have a more holistic understanding of the past.

One doesn’t need a deep understanding and application of Indigenous systems of knowledge to simply acknowledge that other knowledge systems exist, that they are valid, and that they are highly valuable. Even a basic awareness of Indigenous knowledge can open up public understandings to new ways of thinking about the presence of Indigenous peoples in the past rather than their absence from it. The implications of this understanding go a long way toward breaking the implicit barrier between modern Indigenous peoples and the deep past.

As Indigenous archaeologists, we have often struggled with how our own systems of knowledge can be foregrounded as empirical fact-based knowledge from our own contexts.

To do so, we offer a set of culturally specific examples of Ndee and Tewa knowledge systems that present the complexity of the relationships between people, time, land, and place.

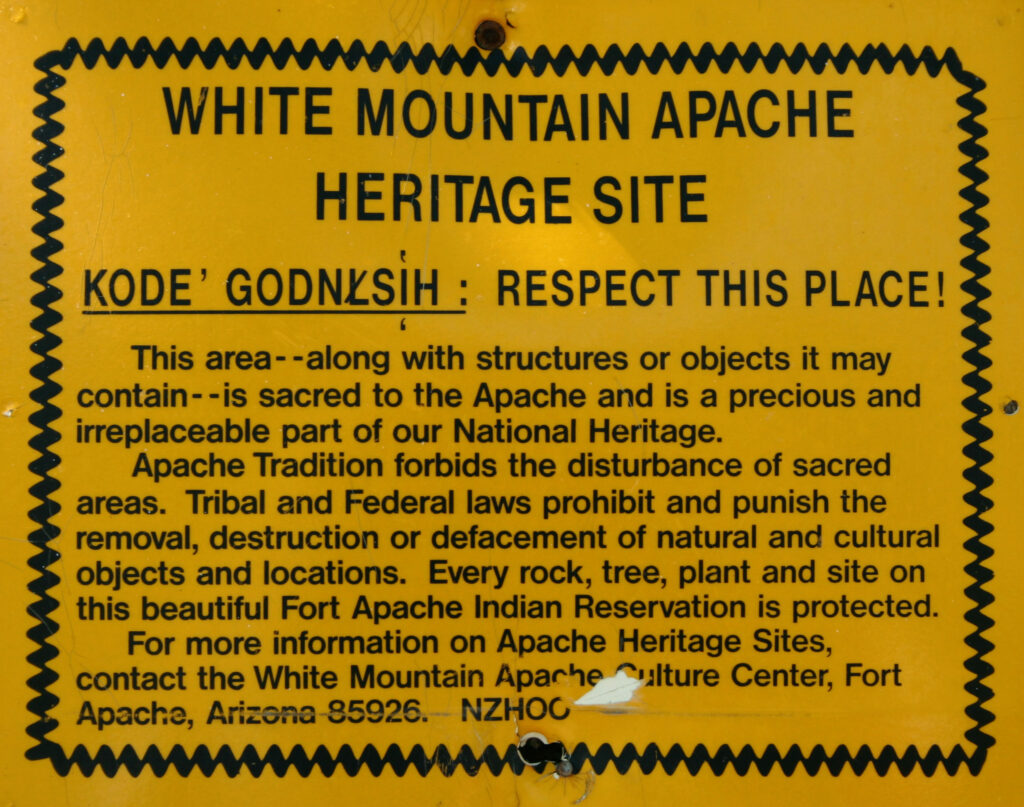

In Laluk’s community located in east-central Arizona, there is a basic tenet of “avoidance” of the past as a means of respect. To non-Ndee archaeologists, this may be something that seems to go against the fabric of archaeological practice. Archaeological excavations and other data collection methods and practices are often intrusive and destructive. Our archaeological tools as Ndee don’t include any trowels. We seek the least impactful ways of approaching heritage management.

However, if one takes time to critically reflect on such a term as avoidance—particularly how it is spoken and implemented in the community context—then other avenues of understanding and interpretation can be explored. For example, in thinking about the term abandonment and the meaning it might have to my own community, there are certain terms that could refer to various types of abandonment: hanalsa or “they took off in a group/left,” ch’inahaskai or “they left/went out,” or even doo hant’e da or “zero/nothing/empty/none.”

In his explanation of Ndee experiences visiting places with community members, anthropologist Keith Basso states, “For whenever the members of a community speak about their landscape—whenever they name it, or classify it, or tell stories about it—they unthinkingly represent it in ways that are compatible with shared understandings of how … they know themselves to occupy it.” In this understanding, Basso foregrounds occupation as presence beyond Western notions of physical human presence that might not reach the core of Indigenous rationalizations from past, present, and future.

Similarly, a basic understanding of the practical and sacred dimensions of movement in Tewa knowledge systems in Aguilar’s community illuminate a complex relationship between people, space, and time. Movement is an element that is present in nearly all aspects of Pueblo life. For example, Origin Traditions, migration, defensive strategies, farming, hunting, dancing—even the movement of animals and natural phenomena like clouds and rain—all feature movement as a core element.

In contrast, a common trope in Southwestern archaeology characterizes Pueblo People as sedentary. They are peaceful farmers who, once established in permanent masonry or adobe constructed homes, stayed put. But what described Ancestral Pueblo People for centuries was their consistent movement across the landscape. The physical Pueblo landscape—including hills, mesas, mountains, lakes, and springs—is overlayed by a highly ordered cosmological landscape on which people exist.

Archaeologists’ focus on the seemingly sedentary nature of Pueblo People has led to a depreciation of the full range and meanings of Pueblo movement across the complexity of space and time. Important to understanding Pueblo movement is the deliberate, both literally and conceptually, return to ancestral places. The ongoing and intentional return to ancestral places speaks to the special reverence and relationship that Pueblo People have with place that challenges presumptions of irreverence and disassociation that are embedded in terms like abandonment.

With this basic understanding of Ndee and Tewa traditional customs of “avoidance” and returning to ancestral places, the public, non-Indigenous archaeologists, and others can reorient their thinking as it relates to Indigenous peoples’ concepts of movement and place. A deeper understanding of these relationships may not be achievable by non-Ndee or non-Tewa people. Yet simply acknowledging these knowledge systems and respecting the sanctity and value of them would go a long way toward bridging Indigenous and Western knowledge systems.

Such Tribally based understandings powerfully exert sovereignty and the ongoing persistence of our peoples from the past to the present and into the future. Appropriate terms and concepts also provide better explanatory power in describing past social dynamics, including community behavior. When Tribal-specific terms are used in appropriate land-based affiliation contexts, they can help bridge the gap between the past and present in ways that a term like “abandonment” cannot.

Following the lead of Indigenous communities, archaeologists and the larger public need to adhere to the cultural protocols and understandings of Tribal nations to better situate cultural and behavioral components of the past and present.

As Indigenous archaeologists, we feel terms like “abandonment” are a prime example of an ongoing lack of social and political justice. Such terms reveal the perpetuation of the settler colonial groundings of the archaeological discipline and subsequent public understandings about the past.

Archaeological terminology, tropes, and designations have the power to shape perceptions that can negatively impact the land. They contribute to continued Western capitalist notions of value, significance, and ultimately what is considered “alive” in the world. This, in turn, contributes to the ongoing lack of real-time action and commitment to effectively change the legal limitations of cultural resource management law, policy, and practice that impact Indigenous ancestral sites and present-day communities.

As the mining threat to Chi Ch’il Biłdagoteel (Oak Flat) shows, this lack of protection has significant repercussions. Indigenous leaders and community activists are fighting to defend this vital place of ancestral and contemporary significance: “You cannot turn your back on a place that is going to be murdered,” said Apache Stronghold leader Wendsler Nosie at the 2021 National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers Sacred Sites Summit.

But even as Biden has paused the process to consult with tribes about the future of Chi Ch’il Biłdagoteel, long-term legal protections need to be put in place so this and other places are protected in perpetuity rather than temporarily or not at all.

Archaeology, as taught and practiced in universities or field settings, can be rather mundane and routine; the impacts of that work may not be immediately felt. However, many within the field do not realize the reach that archaeology has in influencing perceptions of Indigenous peoples—and consequently, how Indigenous peoples are treated in the past and the present.

A trope like abandonment may seem trivial or inconsequential. However, a deeper understanding of the use of such terms can reveal what words represent—human prejudices, morals, beliefs. The utter power of the words we speak and write affect the world around us.

For Indigenous peoples, those effects are all too real. If we can guide the language that is used to describe us and our pasts, we can change other people’s perceptions of us and the places, histories, and issues that we value.