Learning From Snapshots of Lost Fossils

Please note that this article includes images of human remains.

ANOTHER SET OF TEETH

“These teeth don’t belong to Egbert!”

In a museum basement, we huddled over a black-and-white photograph showing pieces of a lower jawbone and its loose teeth. The photo captured evidence of a missing child—one who had been buried 40,000 years ago, only to be discovered and then lost by archaeologists.

This long-lost child, represented only by a lower jaw, was referred to as Ksâr ‘Akil 4 because it was the fourth human fossil discovered at the site of Ksâr ‘Akil in Lebanon, on the Eastern Mediterranean coast.

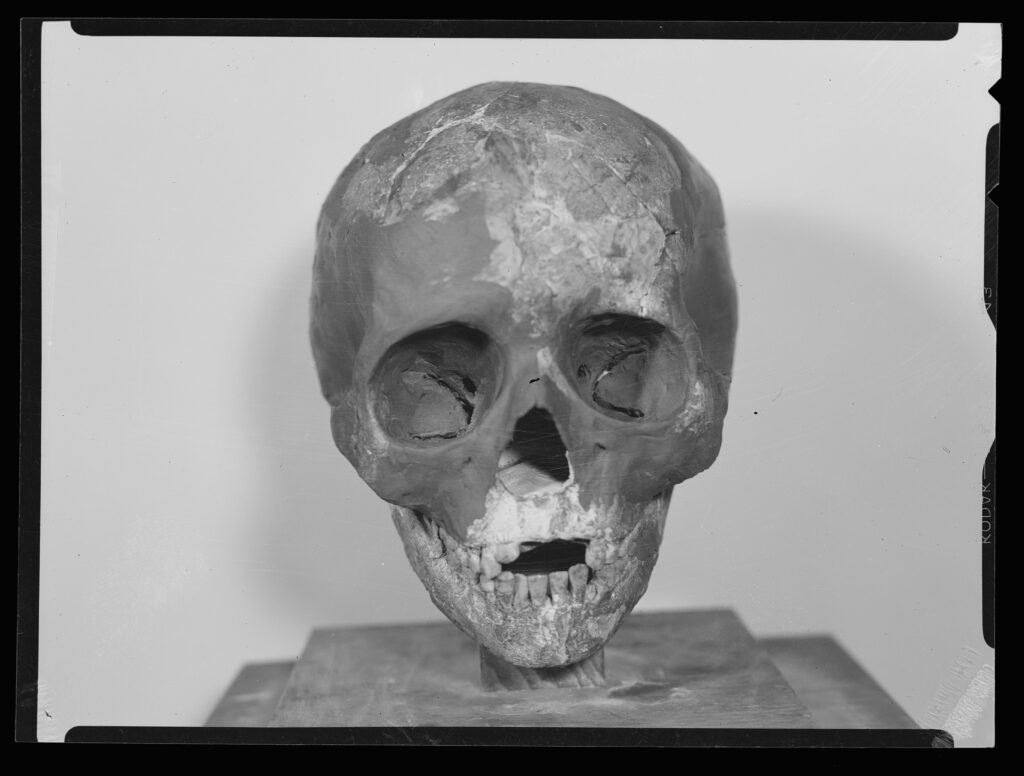

Archaeologists found the remains alongside another fossil called Ksâr ‘Akil 1, which included parts of a skull. Perhaps because this other skull was more complete, this individual was given a nickname: “Egbert.” Like Ksâr ‘Akil 4, Egbert, too, was a now-missing, fossil child. The two children belonged to a population of early Homo sapiens that spread into Eurasia around the time Neanderthals went extinct. Their remains and the artifacts found with them shed light on this major turning point in human evolution.

Before Egbert went missing, scientists cast a copy of the child’s skull, allowing future researchers to study it. No such cast was made of Ksâr ‘Akil 4. Its existence was merely noted as “another set of teeth” found next to Egbert in early publications.

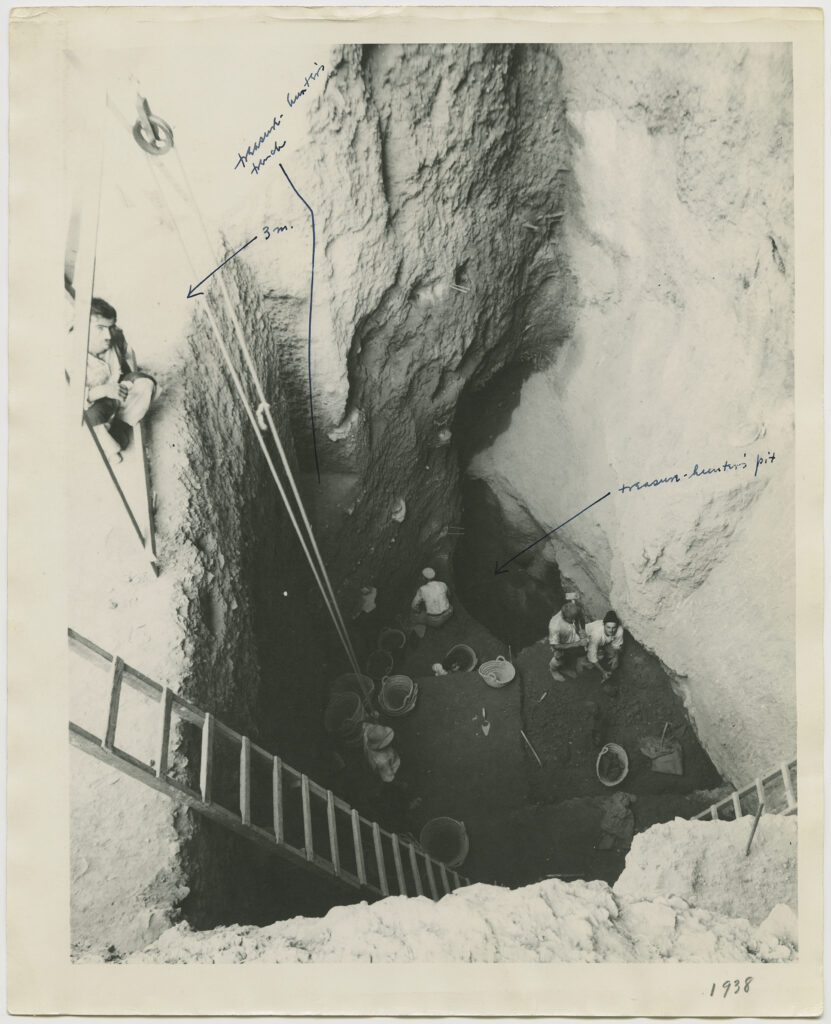

Photos from the Peabody Museum show aspects of the Ksâr ‘Akil research, including excavation trenches and the removal of fossils in cement.

Gift of Nancy Movius, 1998. Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 998-27-40/14628.1.30.

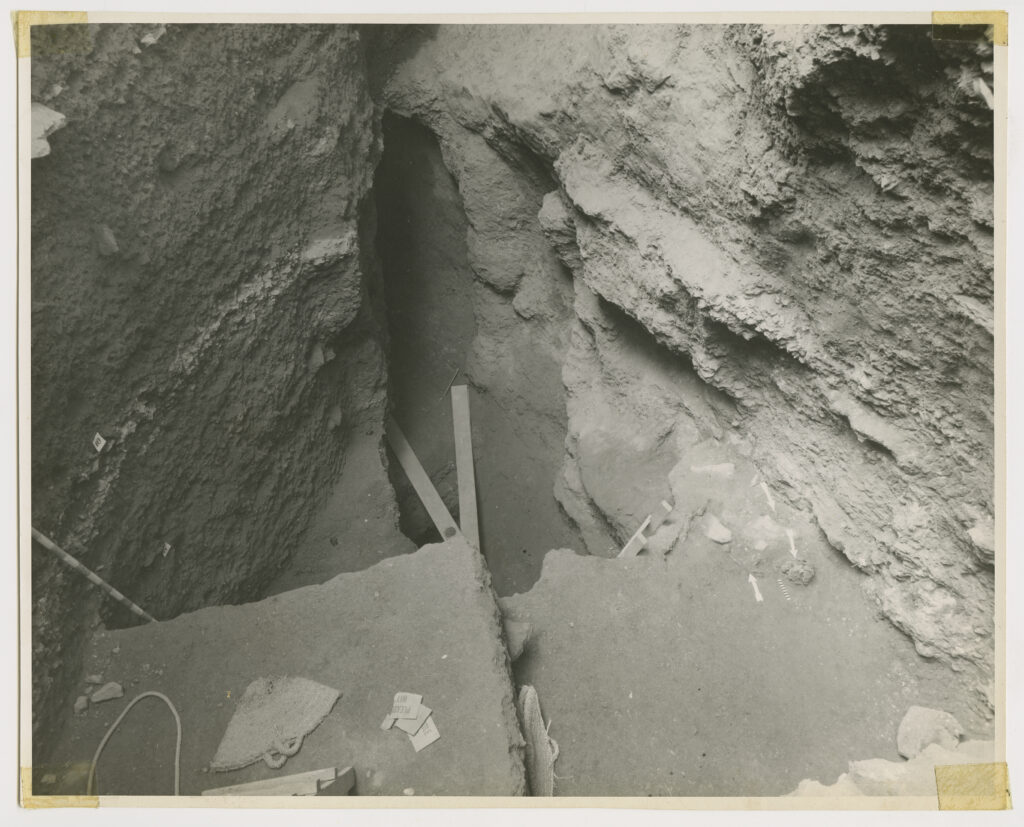

Photos from the Peabody Museum show aspects of the Ksâr ‘Akil research, including excavation trenches and the removal of fossils in cement.

Gift of Nancy Movius, 1998. Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 998-27-40/14628.1.53

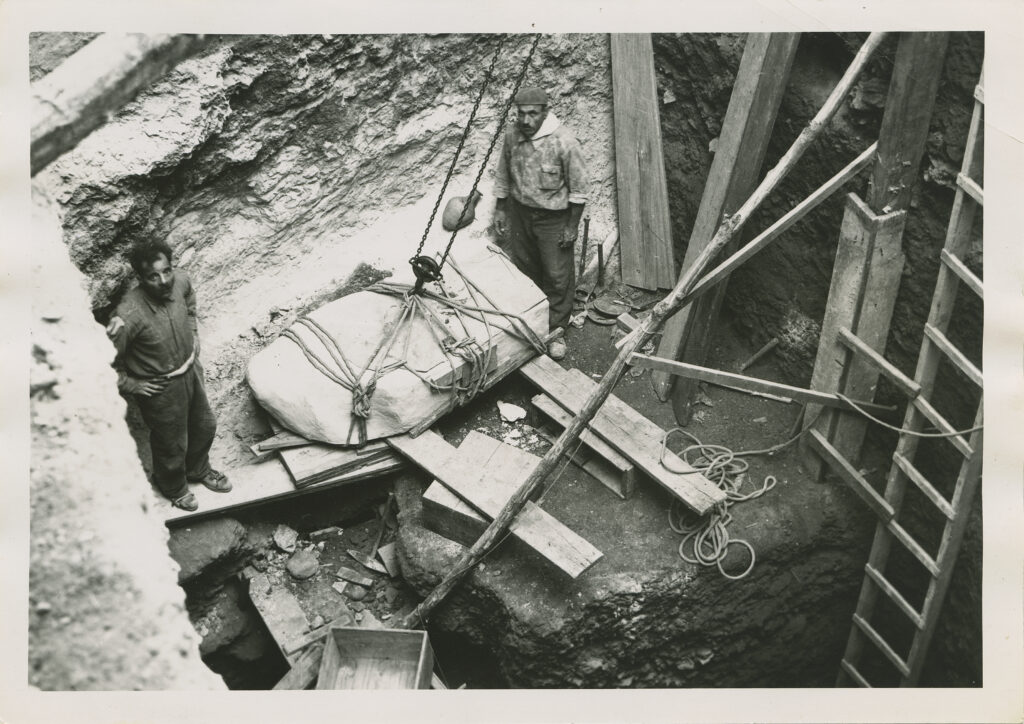

Photos from the Peabody Museum show aspects of the Ksâr ‘Akil research, including excavation trenches and the removal of fossils in cement.

Gift of Nancy Movius, 1998. Courtesy of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 998-27-40/14628.1.27.

Ksâr ‘Akil 4 remained unknown to researchers until 2019 when we—an archaeologist and a biological anthropologist—found a photograph of those teeth within towers of carboard boxes of documents from the Ksâr ‘Akil excavations. From the photo, we learned new details about this pivotal population—a discovery that highlights the importance of archival research and the seemingly mundane paper trail that should accompany any anthropological fieldwork.

FOUND AND LOST

In 1937, American Jesuit priests launched excavations at Ksâr ‘Akil. They dug a trench as deep as two city busses stacked end-to-end that yielded millions of artifacts and food remains. In personal letters written in November 1938, project biological anthropologist Father J. Franklin Ewing discussed a pair of child burials emerging from about halfway down the excavation.

With World War II looming, the team had to seal the remains of Egbert and Ksâr ‘Akil 4 in concrete and leave. Japanese forces intercepted Ewing on his way home to the U.S. via the Philippines. He became a prisoner of war, losing many records of those initial excavations at Ksâr ‘Akil.

After the war, Ewing retrieved the concrete-encased human burials from Lebanon and shipped them to a museum at Harvard University for careful excavation. Here the evidence from the archives is murky, but it appears that only Egbert’s skull and the teeth of Ksâr ‘Akil 4 were successfully extracted. Like the notes and photographs of the early excavations, the other fossils and artifacts once encased in the concrete block are now lost.

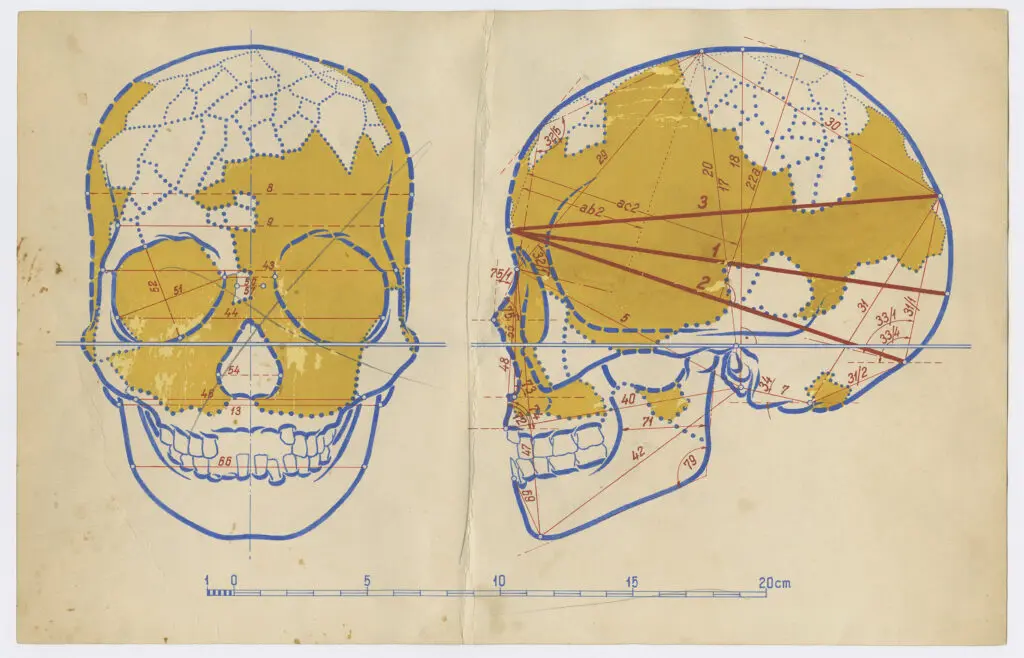

Ewing never published a detailed description of Egbert’s remains. But he was the one to craft a reconstruction of Egbert’s skull before the material was lost. He used large amounts of modeling clay to make “best guesses” about its original form. In the late 1980s, other researchers formally described Egbert’s skull based on a cast of this reconstruction, but nothing was done about the second child.

No one knows where the physical remains of either Ksâr ‘Akil child ended up. Ewing claimed he shipped the fossils back to Lebanon in the 1950s or 1960s. It’s unclear if they ever arrived.

UPPER PALEOLITHIC CHILDREN

Although just children, and only fragments of them at that, the fossils from Ksâr ‘Akil matter. The artifacts found with them attest to cultural and technological changes, known as the Upper Paleolithic, that swept through the Mediterranean region and other parts of Eurasia around 40,000 years ago, just about the time Neanderthals disappeared.

The technological innovations include long-range weapons like the bow and arrow, and expanded diets that could have fed larger populations. Cultural changes at Ksâr ‘Akil and other Upper Paleolithic sites show that these humans also used innovative forms of visual expression. They painted with red and yellow ochre, crafted beads from animal teeth and seashells, and at Ksâr ‘Akil accessed exotic stones from up to 700 kilometers away in what is today central Turkey.

Although just children, and only fragments of them at that, the fossils from Ksâr ‘Akil matter.

These changes associated with Upper Paleolithic cultures likely accrued piecemeal from behaviors gradually developed in Africa or Arabia. Their seemingly sudden appearance as a package in Europe and the Mediterranean could be the result of newcomers with the technologies migrating to the regions. Or perhaps these novel ideas spread among societies already in place.

But most Paleolithic sites only yield stone tools and other artifacts. No fossils to indicate who made the items.

Exceptionally, Ksâr ‘Akil is one of few sites in the Mediterranean in which early Upper Paleolithic artifacts have been found with human remains. Such sites are critical in demonstrating that, whatever the mechanism of their spread, the people responsible for these Upper Paleolithic technologies were H. sapiens—not Neanderthals or some other extinct hominin group.

PHOTOS OF MISSING PEOPLE

The finds from Ksâr ‘Akil interested us both. Bailey is a dental anthropologist who pioneered methods of distinguishing the teeth of H. sapiens and Neanderthals. Tryon, a Paleolithic archaeologist, studies artifacts and sediments from ancient human sites.

Tens of thousands of stone tools from Ksâr ‘Akil had been sitting for decades, mostly unstudied, in wooden boxes in Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography. Tryon was eager to start analyzing the stone tools with colleague Laure Metz (who correctly suspected some of the tiniest ones were used as arrow tips). But first, he decided to inspect the notes, papers, letters, and photographs that documented the site.

Among those papers, Tryon found a series of photographs and X-ray images of human remains and reached out to Bailey to help make sense of them. Some of the photos showed pieces of jaws held together with clay; others showed various fragments apart. We assumed the photographs were of the same teeth—Egbert’s teeth—before and after reconstruction with clay.

Looking closer, Bailey noticed discrepancies between the subtle ridges and valleys of the isolated teeth and those in the clay-fortified jaws.

“These teeth don’t belong to Egbert!” she exclaimed. Although the jaws with clay were Egbert, the isolated teeth must have come from Ksâr ‘Akil 4.

The images allowed us to provide the first scientific description of Ksâr ‘Akil 4. Among other insights, we determined the child was around 8 years old. From the photos and X-rays, we also learned more about Egbert. We confirmed the kid was also around 8 and made a detailed study of the shape of Egbert’s teeth, which had been impossible from the casts alone.

Why the two lost children were buried we will never know. But from the details of their teeth observed from photographs taken more than 70 years ago, we can identify both as belonging to our species, H. sapiens.

At the same time, they exhibit some unusual dental details. Nearly all fossil and most living people have five cusps on their lower first permanent molars (a.k.a. “school teeth” because they emerge around 6 years of age). But only four cusps graced the molars of the lost children from Ksâr ‘Akil.

These sorts of dental differences may be markers of a particular ancient population. Scholars trace these physical markers in people’s bodies across time and space like a trail of breadcrumbs left by ancient groups on the move. Knowing this cusp marker may aid future research on folks some 40,000 years ago—as populations migrated out of Africa, into Africa, or across Eurasia.

EXCAVATIONS IN THE ARCHIVES

Beyond what we learned about the Ksâr ‘Akil youngsters, our experience demonstrates the importance of archival research. It highlights the value of a careful second look at documents, photographs, and materials from excavations that took place decades ago, and the important role museums and archivists play in conserving these records.

Surveys in sun-dappled landscapes and subterranean digs done by lamplight can be thrilling. Naturally, they capture our imaginations. But field research unfortunately tends to favor people with certain degrees of wealth, privilege, and ability. Archival research can be more accessible—and just as illuminating. We have much to learn from the papers left by yesterday’s scholars.