An Archaeologist on the Railroad of Death

In retrospect, I was probably far too young to be whistling that captivating tune of resistance from the Hollywood classic The Bridge on the River Kwai, but I was enthralled. The visuals, the history, the war: I remember feeling genuinely engrossed in the film, despite being a young teenager and understanding little about the struggle portrayed on screen. As a millennial, born in 1989, I grew up with a fascination of wars past, especially movies about World War II. Nothing quite stood out like The Bridge on the River Kwai and the human experience it portrayed.

It is only now, as an anthropologist and archaeologist who has conducted research in Thailand and mainland Southeast Asia, that I recognize the intersection between this film, the history of World War II, and archaeological developments within this region.

David Lean’s 1957 Hollywood film adaptation of the 1952 novel The Bridge on the River Kwai was a hit. It won seven academy awards and was well-received by the public. The tale is loosely based around real events and people. But it alters the timeline and glosses over the truly horrific experience of prisoners of war—even though the production crew and cast did experience their own bouts of dysentery, leeches, monsoon rains, oppressive heat, and accidental deaths while filming on location in Sri Lanka. The cinematic version was still kinder than the reality.

The movie is also missing (though it very nearly captured) a fascinating archaeological sidenote to the story: the extraordinary investigations of Dutch archaeologist Hendrik Robert van Heekeren while he was a prisoner of war.

The China-Burma-India theater, or CBI, is a “forgotten” setting of World War II, less familiar to Americans than the theaters of Europe or the Pacific. The CBI was a particularly awful place to fight. Journalist Donovan Webster once wrote that “for every Allied combat casualty in the war’s CBI theater of operations, 14 more soldiers would be evacuated sick or dead from malaria, dysentery, cholera, infections, jungle rot, and a previously unknown infection called brush typhus.” By Webster’s estimate, roughly 12 POWs died per day.

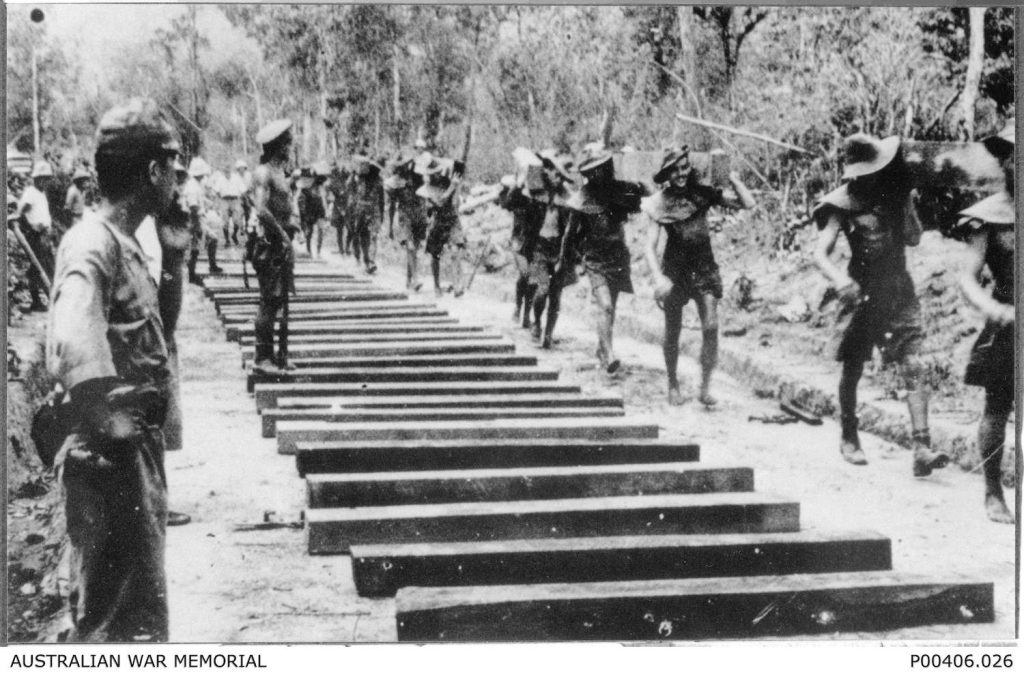

It was here that the infamous “Railroad of Death” was constructed from 1942–1943 over some 260 miles of mountainous jungles. The railway was built by at least 60,000 Allied prisoners of war, of whom about 16,000 died in the excruciating conditions, alongside almost 300,000 civilians from Thailand, Malaysia, Burma, and Indonesia, of whom over 100,000 perished. The POWs and civilian laborers were forced to lay track and build several bridges—including a large span over the Kwae Yai (River Kwai; called the Mae Klong River at the time) north of Kanchanaburi, Thailand.

One of these POWs was Hendrik Robert van Heekeren, an archaeologist born in 1902 in Semarang, Indonesia. Through financing his own research and fieldwork, van Heekeren significantly contributed to the study of ancient Indonesia prior to the outbreak of the war. But, like many of his Dutch compatriots, he was captured after the Japanese invaded Java in 1942. By February 1943, he was forced to work on the Railroad of Death.

While he was a prisoner, suffering from long days of laborious work, van Heekeren intentionally set out to conduct archaeological research. This included examining piles of dirt from the excavations for the railroad—during what must have been precious, short breaks—for artifacts and other finds. He kept copious notes of his research and managed to keep a small collection of artifacts with him at the camp.

The Japanese were quick to confiscate his collections and notes, and punish him, but van Heekeren continued to collect whenever possible. In a journal article that speaks to his dedication to archaeology, van Heekeren wrote, “on only a very few occasions were we allowed to swim across [the Meklong River] and to make hasty, albeit fruitless, investigations on the opposite shore.”

Hendrik Robert van Heekeren’s situation worsened in 1944 when he and other prisoners were transferred from Thailand to POW camps in Japan. For those of you who have read the 2010 book, or seen the 2014 film Unbroken, which depicted the horrific conditions of Japanese POW camps, you can appreciate that van Heekeren’s move was not ideal. Conditions in these POW camps rivaled those of the CBI—illness, malnutrition, and abuse were commonplace.

When van Heekeren was transferred, Japanese soldiers confiscated his entire collection of artifacts. But a friend somehow saved and returned the collection to him after they arrived in Japan. The details are unclear on how this transpired. Then van Heekeren found a way to keep these artifacts safe until the end of the war. Eventually, a portion of these collections, stone tools, specifically, ended up in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Astonishingly, van Heekeren wasn’t the only POW to, presumably, keep his sanity by making collections and practicing hobbies. The Illustrated London News noted, shortly after the war ended, that various prisoners kept ornithological notes and collected butterflies, and in at least one case, a prisoner named Charles Thrale traded food for paper, collected roots (to crush for paint), and used his own hair as a brush to paint and draw scenes from time in the camps.

The most surprising thing about van Heekeren’s story is that after the war, he intentionally returned to Kanchanaburi, to the sites he located while suffering as a POW, and he conducted groundbreaking archaeological research.

The most surprising thing about van Heekeren’s story is that he intentionally returned to the sites where he suffered as a POW.

Hendrik Robert van Heekeren ultimately excavated and published on several significant sites in the region. This included the recovery and excavation of one of the first, if not the first, Mesolithic human burials, likely dating to around 10,000 years ago. He recorded the presence of small seashells and large mussel shells associated with the burials, which has proven quite significant in modern archaeological understanding of past human burial and subsistence practices. Several decades of archaeological research in mainland Southeast Asia have confirmed the dominant role of mollusks in past lifeways for food, ornamentation, burial, and likely much more. Van Heekeren’s early observations helped set the stage for this understanding.

Were it not for van Heekeren’s amateur interest in archaeology growing up in Indonesia, his work before the war, his capture and transfer to the railroad in Thailand, his experience as a POW, his transfer to Japan, and his release and liberation, we may not have the foundational archaeological record in Thailand that we have today.

I often thought of van Heekeren and his experience while my colleagues and I conducted a National Geographic Society–funded survey in northern Thailand to better understand the diversity and distribution of mollusks in relation to archaeological sites. We trekked through rivers and streams, and around limestone karsts, searching underneath rocks, leaves, and other vegetation for bivalves and gastropods. We felt the heat, bug bites, mutual disappoint, and excitement when either failing to find mollusks or finding too many to count and identify. We shared and were inspired by the same overarching question: How did past peoples exploit this environment?

But unlike Hendrik Robert van Heekeren, we could return to our guest house every evening, enjoy a warm, delicious northern Thai meal, and plan out our next days’ surveys.

The movie The Bridge on the River Kwai very nearly captured a small piece of van Heekeren’s story. In 1956, an archaeology graduate student from Harvard, Karl Heider, was apparently hired by the production to play the part of van Heekeren. There was a planned scene of him collecting ancient stone tools along the railroad—a scene that never made it into the final cut.

When I watch The Bridge on the River Kwai now, I am still struck by its vivid representation of this violent and tragic period of history. In many ways, it’s not surprising that Hollywood chose to take on the CBI in film. The 1946 nonfiction book Thunder Out of China itself reads like a Hollywood script:

“It [the CBI] had everything—maharajas, dancing girls, warlords, headhunters, jungles, deserts, racketeers, secret agents. American pilots strafed enemy elephants from P-40s. The Chinese Gestapo ferreted out beautiful enemy spies in our own headquarters, and Japanese agents knifed an American intelligence officer in the streets of Calcutta. Chinese warlords introduced American army officers to the delights of the opium pipe; American engineers doctored sick work elephants with opium and paid native laborers with opium, too. Leopards and tigers killed American soldiers, and GIs hunted them down with Garands. Birds built their nests in the exhaust vents of B-17s in India while China howled for air power.”

Ironically, that description was prefaced with the claim: “No Hollywood producer would dare film the mad, unhappy grotesquerie of the CBI.” The authors clearly underestimated Hollywood’s daring.

Hollywood likes archaeology—just consider its obsession with the Indiana Jones series, which doesn’t seem to be ending anytime soon, or the recent Netflix hit The Dig. Maybe someday Hollywood will remake the story of the railroad of death, and we’ll finally get to see that cut scene: Hendrik Robert van Heekeren, a POW and an archaeologist, endlessly searching the riverbank terraces for ancient tools, seems an excellent candidate for a Hollywood hero.