How Colonialism Invented Food Insecurity in West Africa

It’s the year 2065. West Africa’s cool seasonal rains wake Abena. She rides her bike to work, where she pushes investment in cultivating insects as renewable protein sources.

Abena reflects on the stories she learned from her grandparents. Long before, they had to survive swarms of locusts, harsh winds, and failing crops because the People Across the Sea had poisoned the Earth in pursuit of ever-newer iPhones and other disposable frivolities.

Rather than fleeing the desperate conditions, her grandparents had remained on their homelands and relied on knowledge passed down by their elders. As their ancestors had done during previous hard times, they survived on locust meat, bush leaves, and underground tubers.

Abena now thrives because of the resilience of those who came before her.

This world and character, inspired by the Afrofuturism movement, was dreamed up by archaeologists Amanda Logan and Katherine Grillo. They wrote about Abena—and Akaina, a young girl in Eastern Africa living 3,000 years from today—to help teach K–12 students about possibilities for a sustainable future. To imagine those futures, the scholars resurrected sustainable lifestyles of the past known from archaeological research and African Oral Histories.

I am an anthropologist who finds this work innovative and important. I felt compelled to share this story as an example of the power of archaeology to shift perspectives.

In West Africa, these data show that past communities in what is now Ghana, where Logan works, thrived for centuries without famine, even through one of the worst droughts in the region’s history. Yet today, Ghana has a nearly 25 percent poverty rate and over 21,000 people facing food insecurity.

Finding a past of plenty, Logan and her collaborators trace Ghana’s current food scarcity to European colonialism, especially during the 1800s. These scholars are using their research on the precolonial past to sow sustainable futures—like the worlds inhabited by Abena and Akaina.

BOTANICALS AT BANDA

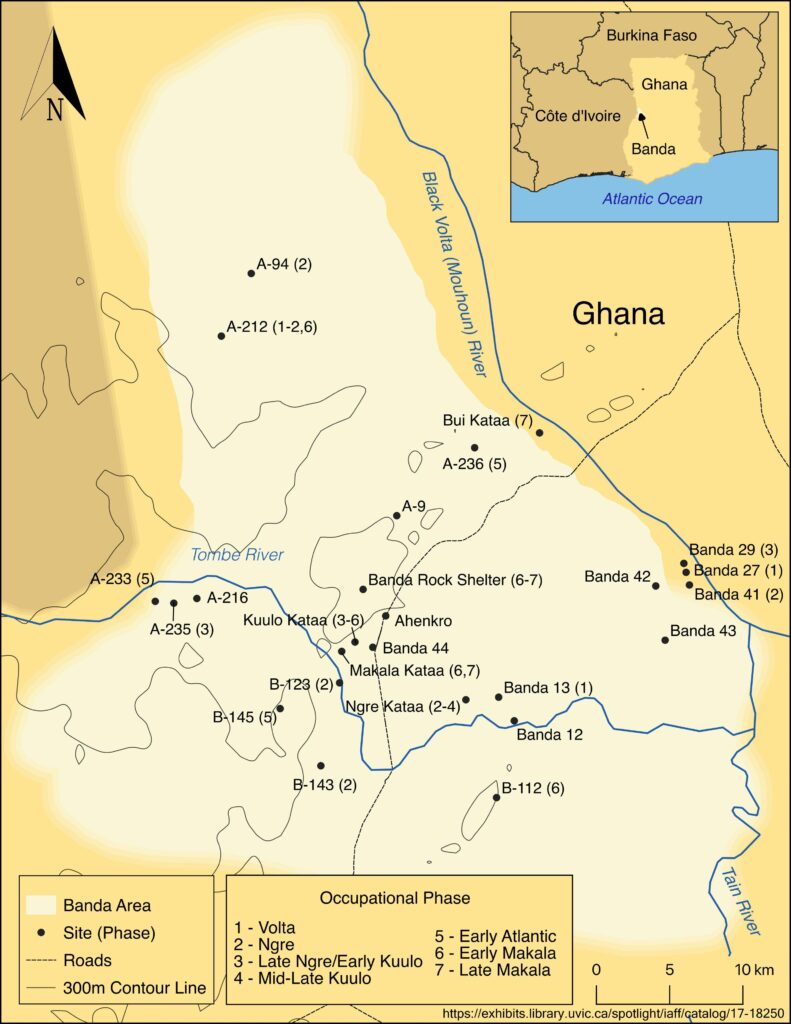

Much of this research took place at Banda, an archaeological site in western Ghana. Near the border with Côte d’Ivoire, today the site sits in a grassy savanna dotted with trees.

Six hundred years ago, across a varied landscape, balmy woodlands abutted savanna and arable farmland south of the Black Volta River. Farmers planted grains to make traditional dishes such as starchy, mild fufu and thick, warm tuo zaafi, and households stored surplus tubers in their wattle-and-daub homes to nourish them throughout the year.

Multiple languages are now spoken in the region by the Nafana, Kuulo, Ligbi, Mo, and Ewe people, whose ancestors lived there for several thousand years. Since the mid-1980s, archaeologists with the Banda Research Project and Banda Heritage Initiative have uncovered locally made objects such as stone tools, iron blades, and clay cooking pots, alongside trade items like beads and jewelry.

Logan, now a professor at Northwestern University, started working at Banda as a graduate student in 2007. Developing her specialization in archaeobotany—the study of plant remains—she has been interested in how food traditions changed over time, especially alongside political and environmental shifts.

She had plenty of material to work with. Excavations at Banda yielded a trove of partially burnt seeds and nut shells. Based on distinct microscopic features of these seeds and nut shells, Logan and her team identified the remains as pearl millet and sorghum, suggesting these plants were part of people’s diets beginning at least 700 years ago.

The presence of these native grains surprised the archaeologists. Historically, researchers have assumed that West African farmers replaced Indigenous crops with corn, which was introduced from Central America in the 1500s and is known to often yield bigger harvests.

While Logan’s work revealed the plants Banda residents ate, other research reconstructed the region’s broader environmental history. The Banda region usually sees seasonal monsoons from late spring through early fall. But analyses of sediments from lake cores and tree rings revealed that West Africans endured a “mega-drought” for more than three centuries between 1400 and 1750.

The cultivation of grains like pearl millet and sorghum, which are drought resistant, may have helped people survive the harsh, unpredictable climate conditions.

THE TRADE IN ENSLAVED PEOPLE AND FOOD INSECURITY

If Banda did not have food stress in the past—even during the past millennium’s worst drought on record—why is hunger a problem in West Africa today?

Food insecurity in Ghana did not become a widespread issue until the 1700s and 1800s, as shown by Logan’s archaeological evidence as well as Oral Histories. That’s when British colonizers switched their trade focus from gold to human beings, and the trade of enslaved people intensified in West Africa and across the Atlantic.

In addition, colonial economics created food shortages in Banda and across West Africa. Much less grain entered household storage or local barter systems, as most was sold in markets or directly taken by British soldiers. Local people have passed down stories about this period, recounting how their grandparents struggled to eat and turned to less-desirable foods like cassava.

“The slave trade not only rewrote what was valuable and what mattered in terms of economy, but it also removed a lot of people who [were] in their prime,” Logan told me when I interviewed her. Those people held valuable knowledge about farming and food production.

Dela Kuma, a University of Pittsburgh archaeologist who studies 19th-century Afro-European trade, noted to me in an interview that after the slave trade ended, Ghana continued to be an important global exporter of products such as palm oil. Such trade continues to siphon away resources from West Africa to the Global North, Kuma says.

HOMEGROWN SOLUTIONS

The food history from Banda sparked Logan and Kuma to think more broadly about how non-African scholars and humanitarian groups have understood food insecurity on the continent—and why outsiders’ interventions often fail.

“There’s been this long-standing argument—and this is something that comes out of the colonial narrative—that parts of Africa have just always been food insecure because their agriculture, environments, or crops are inferior,” says Logan. But, as the data show, African farmers were knowledgeable and successful for thousands of years. Outside forces uprooted that security.

Logan and Kuma began to challenge assumptions about why and how hunger became a modern problem in West Africa. As Logan wrote in a 2016 American Anthropologist article, “chronic food insecurity is a condition that was made rather than a condition that has always been.”

The botanical evidence showed that people were not desperate for the high yields that corn provided. Instead, people continued to grow and eat West African grains. But why not grow corn, which often provides more harvestable food per field?

As Logan details in her 2020 book The Scarcity Slot, West African farmers often have preferred to cultivate crops with methods developed over centuries that reduce long-term risks, rather than generating high yields in the short term. Rather than switching to an introduced grain that might be more “efficient,” communities stuck with time-tested crops that were familiar and important to local cuisine.

According to Kuma, many outsiders’ solutions for hunger are removed from Indigenous practices and foods. As an alternative approach, she seeks input from the people who reside around her current research site in the Amedeka-Akuse community in southeastern Ghana.

“My goal is to bridge the gap between academia and the local communities that we study with,” Kuma says.

UNITING PASTS AND FUTURES

Logan emphasizes that understanding the history of food in West Africa should inform how scholars, humanitarian groups, and governments approach contemporary food insecurity. Her research shows that people knew what they were doing.

Human history on the continent is full of similar stories of resilience through environmental challenges. Logan and her collaborators hope to uncover these stories as part of a new multiyear project.

Currently, Logan is working with Alemseged Beldados Aleho, an archaeobotanist at Addis Ababa University in Ethiopia, whose work with colleagues shows farmers were successfully cultivating sorghum, t’ef (a.k.a. teff)—a native African grain—and millet in Eastern Africa for millennia.

Logan is also collaborating with an international team at archaeological sites in the ancient Yoruba city of Ilé-Ifè in present-day Nigeria to determine how people fed a large population during the medieval period. Building archaeobotanical datasets from sites across the continent will help uncover the range of strategies Africans historically used to feed themselves, Logan says, and “hopefully encourage a shift in development initiatives today.”

Logan does not shy away from the political implications of her work. “If we’re really committed to solve ‘the problem of African food insecurity,’ we have to deal with the way those unequal economic systems benefit many of us in the Global North,” she says. “We’re basically siphoning off the food security of people in the Global South and have been for centuries.”

By uncovering ancestral food systems, archaeologists and local communities can work toward vibrant, sustainable worlds like those imagined for Abena and Akaina—futures rooted in African pasts.