Excavating My Dad’s Life

In 2019, I lost my dad.

Not long after, we decided to sell the old, grand house I grew up in—a home my dad fell in love with in the 1990s and bought before my mom had even stepped inside. As our family organized the house to put it on the market, I decided to excavate my father’s study as if I were an archaeologist surveying a site that would soon be lost to development.

I felt compelled to embark on this deeply intimate project because there were, and still are, elements of my dad I do not understand. He was opinionated, a voracious reader, an elaborate storyteller, and someone who battled with alcoholism and secrets. When he died, we hadn’t spoken in months. I saw this exercise as a chance to get to know details about him that might not be recoverable after we sold the house.

Of course, I was familiar with many of my dad’s objects and the home’s idiosyncrasies. I had learned by heart the choreography required to avoid the creaky floorboards and which bookshelves provided footholds for optimal free climbs. But I knew that using the methods of archaeology would reveal new insights.

As an archaeologist, I pay attention to context. A coin by itself might be a unit of ancient currency, but if found at the bottom of a well, it’s a wish.

Using this approach allowed me to recover the invisible relationships among my father’s possessions. I found unknown layers of who he was, including his pride, his fears, and his desires.

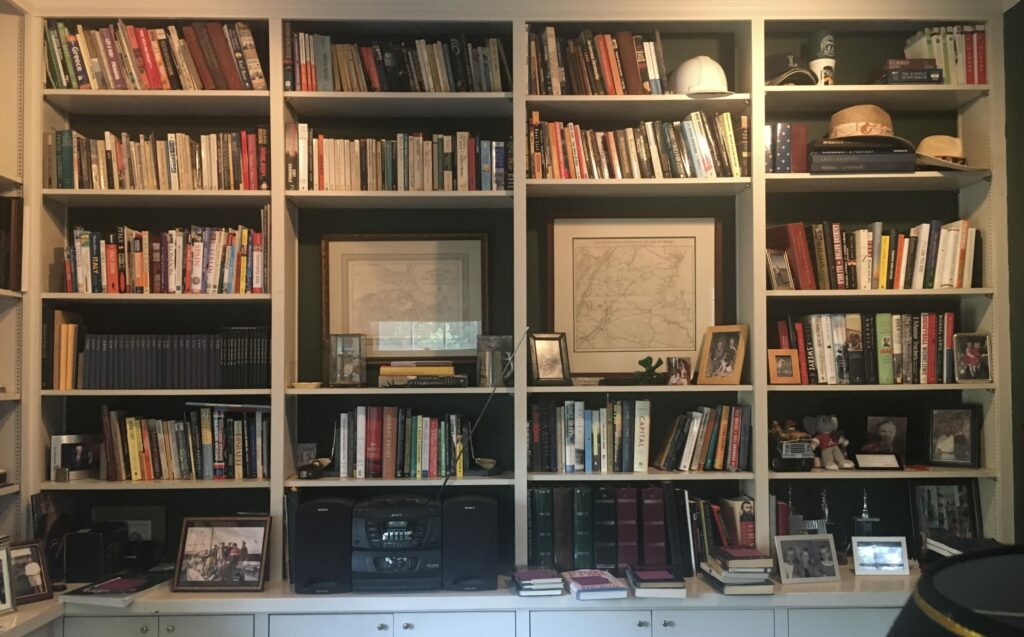

Archaeologists use many techniques to understand past and present. Often, we first decide on the scope of study. In this case, I used the four walls of my dad’s office as the boundaries of my excavation square. I created a “site plan,” in which I drew a blueprint of his furniture and the room.

Archaeologists then excavate soil layer by layer. Sometimes there are clear indications that objects go together, like a hearth and cooking utensils united by soot. These are often called “loci,” in which a locus relates to a certain moment or action in time. So, I assigned each of my dad’s bookshelves, which he had arranged in deliberate themes at different moments in time, their own “locus numbers.”

I understand this arrangement of objects to be a sort of performance.

A general rule in archaeology is that the deeper the objects are, the older they are. In the case of my dad’s bookshelves, the stratigraphic sequence was reversed. The higher shelves represented the oldest moments in time. Only accessible with a stool, they remained little altered from the 1990s, when my dad first moved in and arranged his possessions.

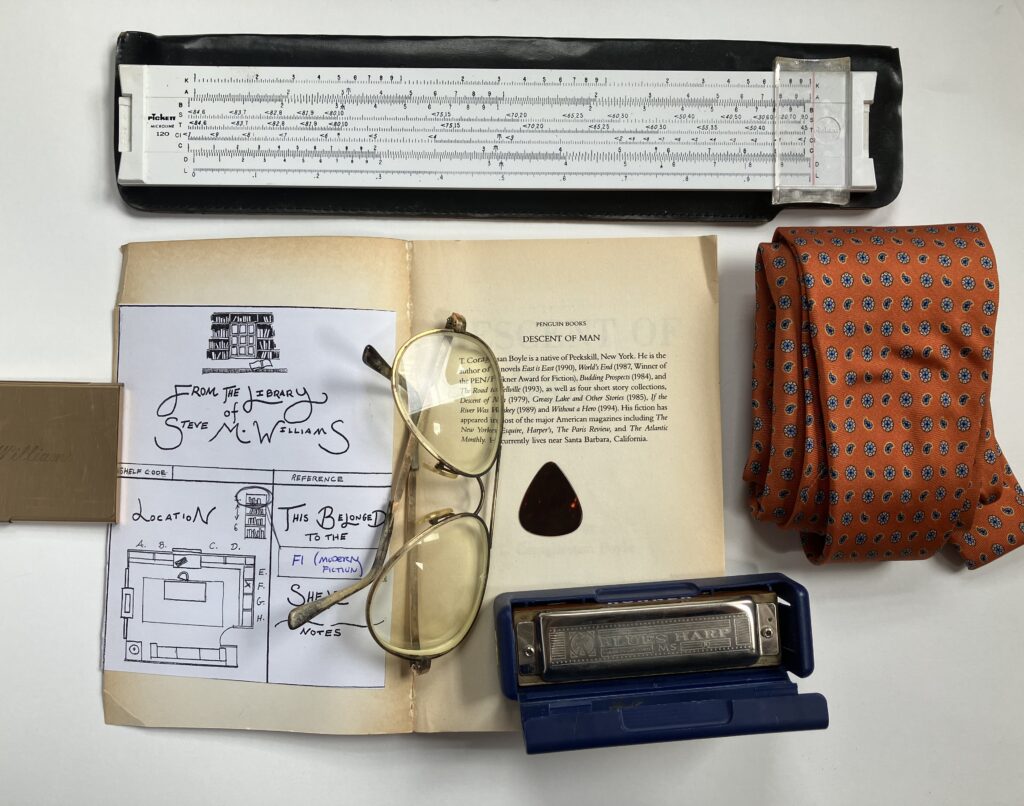

Archaeologists label everything, so I labeled his books. For the ones we gave away to loved ones, I included a sticker featuring the blueprint of his study, with an X marking the spot where the book had been located. I have many books from F3, the locus of historical fiction and essays. These books are well-worn, with creases and yellowed pages—the paperbacks wrinkled from being stuffed in briefcases in the 1980s.

On the top shelves, just within his reach, I located the era when my dad was close to my current age. He had displayed his college degree alongside old book collections bought as sets, their spines unbroken. On the eye-level shelves, I found the things that moved around a lot—the paperbacks and CDs he touched, reached for, and re-arranged.

I understand this arrangement to be a sort of performance. In archaeology, objects that show little use are sometimes interpreted as being mainly for ceremony or special occasions. For my dad, the leatherbound books were meant to convey the intellect of someone who reads the canon. He was trying to fashion the kind of distinguished gentleman he imagined to be the only person worthy of occupying such a room. But his T.C. Boyle novels—satirical and popular, their chapters filled with misguided male heroes, humor, and addiction, and their covers marred with coffee stains and wrinkles—were clearly the ones he actually went back to.

On the bottommost shelves and cabinets, I found the hidden things.

Self-help books were discreetly tucked in a back corner, but nevertheless impeccably organized. Their arrangement conveyed to me his acknowledgment of the gravity of his illness, while their obscure placement suggested a level of discomfort.

In the very far back of his desk drawer, I found his sobriety tokens—plastic coins given by Alcoholics Anonymous to mark the length of time someone has remained sober. They were within reach but still hidden, even if the drawer was completely pulled out. I imagine this position allowed him to hold the weight of the tokens in his hand without ever having to bring them into the light—a tactile but discreet reassurance.

In one cabinet, I found a file of every assignment he had ever written for college, stored next to piles of tax documents. This juxtaposition conveys to me that, for him, the two elicited the same anxiety to keep impeccable physical evidence, as if someone would question his degree and audit him in the same stroke.

Similarly, I found his short stories and poems next to law school acceptance letters—a file of potential lives unrealized, shelved in the same realm of possibility.

By paying close attention and creating a personal archaeological record, I preserved the intangible moments of arrangements and decisions my dad had made. It’s the context of the room itself I will miss most, the thing that makes all of these items have meaning. I will miss the way he arranged his world.

Despite the loss of our family’s archaeological assemblages, there are moments we continue to find them. A year after we sold our house, I brought my dad’s guitar back to Philadelphia. It comfortably lived snug in its case for months (an unrealized pandemic project) before I released it into the new habitat of my home.

In the outermost pocket of the case, along with several guitar picks, were sheets of folded and crumpled paper. When I opened them, I saw they were the lyrics of the last piece my father was trying to learn: the Loudon Wainwright III song “Daughter.”