Navigating the Ethics of Ancient DNA Research

This article was originally published at Knowable Magazine and has been republished with Creative Commons.

THE 2022 NOBEL PRIZE in physiology and medicine has brought fresh attention to paleogenomics, the sequencing of DNA of ancient specimens. Swedish geneticist Svante Pääbo won the coveted prize “for his discoveries concerning the genomes of extinct hominins and human evolution.” In addition to sequencing the Neanderthal genome and identifying a previously unknown early human called Denisova, Pääbo also found that genetic material of these now extinct hominins had mixed with those of our own Homo sapiens after some of our ancestors migrated from Africa around 70,000 years ago.

The study of ancient DNA has also shed light on other migrations, as well as the evolution of genes involved in regulating our immune system and the origin of our tolerance to lactose, among many other things. The research has also ignited ethical questions. Clinical research on living people requires the informed consent of participants and compliance with federal and institutional rules.

But what do you do when you’re studying the DNA of people who died a long time ago? That gets complicated, says anthropologist Alyssa Bader, a co-author of an article about ethics in human paleogenomics in the 2022 Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics.

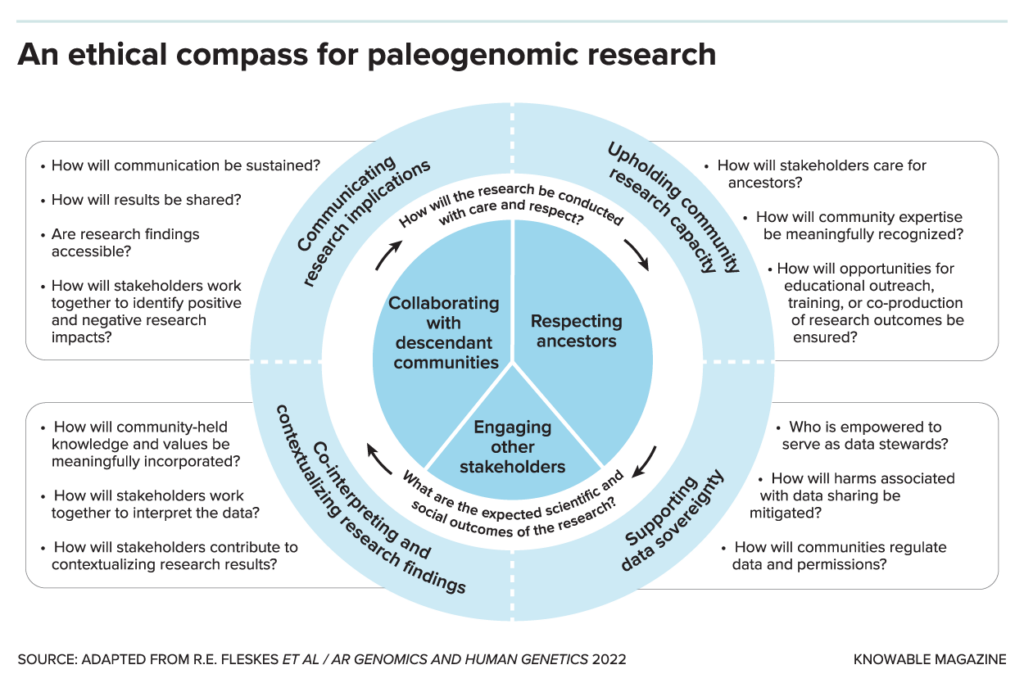

“Consent takes on new meaning” when participants are no longer around to make their voices heard, Bader and colleagues write. Scientists instead must regulate themselves and navigate the sometimes contradictory guidelines—some of which prioritize research outcomes; others, the wishes of descendants, even very distant ones, and local communities. There are no clear-cut, ironclad rules, says Bader, now at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, “We don’t necessarily have one unified field standard for ethics.”

Take, for example, research at Pueblo Bonito, a massive stone great house in Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, where a community thrived from A.D. 828 to A.D. 1126 under the rule of Ancestral Puebloan peoples. In the late 1800s, archaeologists from the American Museum of Natural History started excavations there, unearthing more than 50,000 tools, ritual objects, and other belongings—and the remains of 14 people. These human bones remained stored in boxes and drawers, allowing non-Indigenous researchers to study them. Recently, a research team extracted and analyzed their DNA. The study, published in 2017, suggested an exciting finding: The remains found in Pueblo Bonito once belonged to members of a matrilineal dynasty, and leadership at Chaco Canyon was likely passed through a female line that persisted for hundreds of years until the society collapsed.

But the research sparked fierce ethical discussions. Several anthropologists and geneticists, Bader included, criticized the study for its lack of tribal consultation—the Puebloan and Diné communities, who still live in the area, were not asked for permission to carry out the research. The critics also cited the dehumanizing language (such as “cranium 8” or “burial 14”) that authors used to describe the Pueblo ancestors and warned that the controversy would exacerbate feelings of distrust toward scientists.

Bader spoke with Knowable Magazine about what we can learn from research on ancient DNA and why considering the ethics around it is such an urgent task for the field. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What is ancient DNA? And where can we find it?

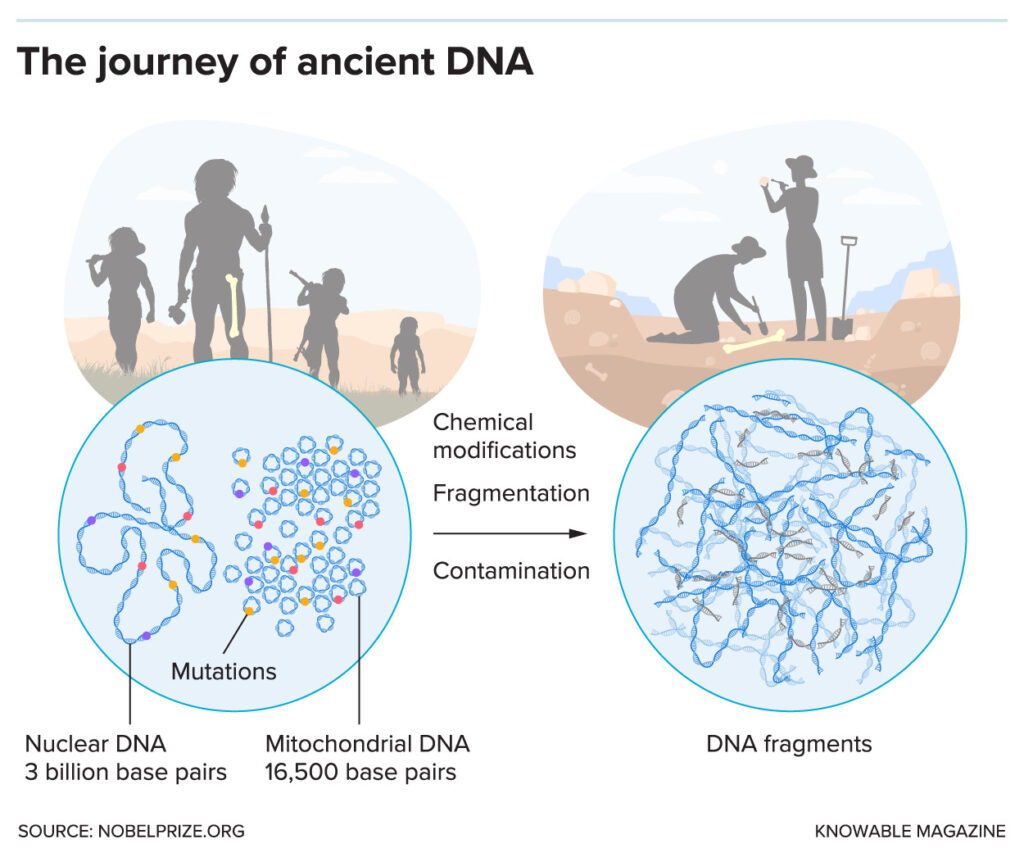

Well, ancient DNA is the DNA that’s been preserved over hundreds or thousands of years. And it can be from humans, from animals, from plants, from microbes, viruses, bacteria.

An easy explanation would be “DNA from nonliving beings.” We have DNA from woolly mammoths, we have ancient DNA from Neanderthals, and we have DNA from more recent human ancestors. So, it’s a huge span.

If we’re talking about DNA from humans, we can get it from teeth, from bone, from hair. We find it from coprolites, which is poop. We can get it from something that someone chewed on. Any way that you would leave your DNA now as a living human could also potentially be preserved for the future as well.

With the development of next-generation sequencing technology, there has been a dramatic proliferation of research on ancient genomes from ancestral humans, from very few published before 2009 to more than 1,000 by 2017. What have we learned from peeking into the genomes of ancestral humans?

Oh, there are a lot of different types of questions that we can address by looking at the DNA from human ancestors. We can see how closely or distantly related they were across continents, across time spans. We can see population movements. We can see how humans and their environments interacted.

But all of it, I think, boils down to just understanding a little bit more about what makes humans who we are now. Ancient DNA is simply using a genomic perspective to understand what things happened in the past to shape what humans are today.

This is something that you’ve also tried to do with your own research, right?

Yes. Part of my family is Tsimshian from southeast Alaska. I grew up in Washington state. But when I was a kid, and even now, one of the things that I really enjoy doing to maintain a close relationship with my family in Alaska is to go up and spend the summer fishing. I just went fishing with my grandpa, my uncles, and my dad last summer.

That influenced the research I do now, which is thinking about how traditional foods—such as salmon, in my family—shape people’s oral microbiome, the community of bacteria that are in our mouths. And there’s been research showing those bacteria can impact our health outside of the mouth. If they get out of balance, they can cause problems in other areas of your body. They can also support your health.

My research looks at the relationship between traditional foods in Indigenous communities of the Pacific Northwest, mostly in Alaska and British Columbia, and how they can support the biological resilience and health of these communities. In short, understanding the way that our diet might be impacting our health on a microbial level.

And you’re also studying the oral microbiome of Tsimshian ancestors.

Yes, we’re comparing the microbes that we find in our ancestors’ mouths with microbes in descendant communities, and trying to answer what folks are eating now, what ancestors were eating in the past, how that stayed the same, how that’s changed through time, and then how that correlates with the microbiome.

When scientists study the DNA of living people, some sort of institutional committee reviews those projects to make sure they are carried out in an ethical manner. What happens when the people you study have been dead for a long time?

The idea of consent and what it means in the context of ancient DNA research is a big challenge in the field. Ancestors themselves don’t have a way to either consent to being part of research or to withhold their consent, the way that a living person who opts into genetic research can. We don’t have a good way to do that with ancestors.

There are a lot of different approaches that researchers take to that, though the one I advocate for, and model my own research practice after, is what we call community-collaborative research. Here, descendant communities stand in for the ancestors, and part of that is because data from ancestors can impact these modern communities.

In what way, exactly?

Well, we can’t really act as if ancestors just exist in this “prehistoric” or “historic” bubble and that understanding or learning new things about them doesn’t impact folks who are living now.

These things can tell us a lot about a specific group of ancestors, sure, but they might also be part of the history of living communities. For example, there are researchers looking at relatedness between communities, looking at population histories and migration and movements.

How do you approach your research on the field and with the communities involved?

My approach is about building the relationship with the community as research partners. So, I’m not just approaching for permission.

For example, for one of the communities that I worked with, I went out there, introduced myself, and had community meetings. I talked about my research expertise and the types of things I was interested in—but I also heard the kind of research that they were interested in. Then we were able to chat about what methods could be used to explore those mutual research interests and plan the project together. I got formal permission to go to the museum where their ancestors were, to be able to look at them and collect samples from them.

I provided updates about where we were in the research process. This was before COVID-19, so I went out every summer to provide updates. And then, when we started to get data from these analyses, I was interpreting that data with the community. Instead of me presenting it as, you know, “These are the results; this is what the science says,” I was like, “This is the data, this is how we generated it, this is how it’s often interpreted. How should we think about it in the context of community history and community-held knowledge?” That enhances the scientific outcomes.

Did it help that you’re Tsimshian and were familiar with community values, culture, and traditions?

I think that the biggest influence that has had is that it’s shaped how I hold myself accountable to my community research partners. So, when I’m doing the work and talking to people, I think: “If someone was approaching my family, how would I want them to be treated?” That has a big impact on the way I construct my research collaborations and also on the way I have turned away from, or pushed away, some of the extractive processes where communities aren’t consulted or are treated as a resource, as something researchers use as they need.

You also mentioned that researchers may follow different approaches to these kinds of ethical issues. Can you talk about this apparent lack of consensus?

The thing about ethics is that they’re culturally constructed. Two different people might have different ideas of what is or is not ethical. And those ideas can also change over time. I think we see a little bit of that with research.

In the review article, we talk about there being some tension. Some folks really orient the research around stakeholders like local and descendant communities, and how it impacts them. You can also take the approach that research is done for the sake of knowledge, regardless of how or who it impacts.

So, depending on how you orient yourself around these perspectives, you might shift your research practices in a specific way. But we don’t have one set of rules or something that everyone is held accountable to. There are no formal consequences if you don’t abide by one of the ethical guidelines, some of which even conflict with one another.

I think there are benefits to there not being one concrete thing, because that means you can adapt to different situations. If you write one set of rules, that also creates limitations. But it also means that it’s difficult for folks to sometimes figure out what they should be doing.

What kinds of mistakes have been made?

Particularly in the context of North America, the remains of Indigenous human ancestors have been taken from their communities and used as a resource for researchers. Sometimes communities knew about it and objected. Sometimes communities didn’t even know where their ancestors were or what they were being used for.

These remains have been collected in museums, displayed in ways that communities didn’t approve of or felt were disrespectful. And in a museum context like that, non-Indigenous scientists didn’t necessarily have to go to a descendant community and ask for permission to do their research. This just continued a history of violence, harm, and exploitation.

As ancient DNA came along, then those ancestors’ bones and remains became a source for genomic research. But we don’t want these harms, which came out of archaeological research more broadly, to continue to proliferate in genomic research. We want them to stop.

How can this community-centered approach you advocate for facilitate more collaborative research?

Genomic data is just one form of information, right? If you think about what makes you as a person, your genes that come from your family and ancestry are one part of what makes you who you are. And I think the same is true for paleogenomic research. The genomes that we study using ancient DNA are one part of a really big story.

When you collaborate with communities and you include community-held knowledge or histories, that improves the narratives that we’re able to tell using genomic information. It can only improve things, because we have more depth, more perspective on the story that we’re trying to tell through genomes.

In my view, the people who should have the most voice in research are the people who potentially bear the most risk from research. Researchers can cause harm by taking samples from ancestors, excluding communities from giving permission, or excluding them from being involved in the research process.

In a deeply collaborative approach, communities are our partners. They’re not only giving consent for samples from ancestors to be taken, but also helping to shape the research questions. Maybe the methods. They are involved in interpreting the data. Or preparing results for publication. Of course, that all depends on how deeply a community does or does not want to be involved in the process.

For you, what does it mean to think ethically about ancient DNA research?

When I think about what may or may not be ethical, I try to think about the way that harm has happened in the past.

So, when I think about how I want to do my research now, I hold myself accountable to communities when I do my work. I don’t think about research as being just a value-neutral thing. I try to think about how my research will impact other people: who will benefit from it and how I can prevent harms in doing it.

It’s this kind of restorative-justice approach where you say, “Folks were excluded in the past, and we want to include them as much as possible now to heal that harm.” To me, that can be achieved by finding new ways to break down the barriers between who is being researched and who is doing the research.