The Macabre and Magical Human-Canine Story

On a dusty plain, east of the Tigris River in Iraqi-Kurdistan, lies the ancient settlement of Tell Surezha. This excavation site is a remnant of a period and place where the world’s first known urbanized civilization took shape as humans transitioned from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age around 7,000 years ago.

Archaeologists have been digging at Surezha since 2013, uncovering insights into early human behavior and the evolution of society. In 2019, Max Price was studying bones collected from the site by colleagues from the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute. One particular building, with burned mud-brick walls, featured a collection of artifacts, including ancient stamp seals, a tortoise-shaped vessel, a stone mortar and pestle, and a large deposit of animal bones.

The Oriental Institute scholars had sent Price some of these bones because he is a zooarchaeologist, an archaeologist who specializes in studying animal remains, at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Among the collection of bones from sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs, what caught his attention was the quantity of dog and wolf bones. Cut marks and burns on the bones suggested people butchered and ate these animals—including the dogs.

Examining the bones, Price—whose work has explored the use of pigs in the ancient Middle East—began to wonder about dogs in the context of other domesticated animals. How important were dogs as a food source in the past? He embarked on a dig through the academic literature, searching for examples of cynophagy: humans eating dogs.

While there were some discussions, he found dogs to be generally ignored as a major source of protein. “Eating dogs, or possibly using them for skins, is a part of human behavior that we don’t like to talk about,” he says. “I think that that’s been colored by extant taboos in the West.”

Price’s research comes at a moment when a growing number of archaeological finds and genetic analyses of ancient animal remains are adding layers of nuance to the story of domestication and partnership. Canines and humans, through their dynamic interactions, have formed one of the most unique, complex, and mutually beneficial relationships in history.

“There’s a million things a dog can do for you kind of all at once,” says zooarchaeologist Angela Perri, of the University of Durham in England. “That’s why dogs are unlike any other domesticated animal that we have,” she adds.

Though much is still unknown, it is increasingly clear that this bond formed in the distant past not only shaped dogs into the animals we know today—but also helped drive the cultural progression of human society. Dogs’ many, varied roles may therefore offer insight into changes in human communities.

“The story that a lot of readers in the West want to hear is that dogs were domesticated to be human’s best friend,” Price says. “The reality is—as any archaeologist could tell you—that the relationship is more complex.”

Long before humans brought the cow, the pig, or the plant in from the wild, Neolithic hunter-gatherers tamed an ancient, now extinct species of wolf. That the dog was the first domesticated species is perhaps the only part of the story all researchers agree on.

The exact region, timing, and methods of canine domestication are all under debate. The partnership between human and wolf likely started more than 15,000 years ago. Scholars have proposed domestication originating in Europe, East Asia, or the Middle East. It’s also possible that the domestication of wolves into dogs happened more than once, in separate locations.

Much of the literature points to the coldest part of the last ice age, between 27,000 and 19,000 years ago, as a crucial period. This overlaps with the Last Glacial Maximum, a time of climatic instability, when ice sheets expanded and temperatures dropped. Humans were living in hunter-gatherer-fisher groups at this time. They exploited a range of refuges, moved around to find water and resources, and fished and hunted game, including, in some regions, mammoths and ungulates (hooved animals, such as ibex and deer).

For example, in a study published this year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Perri and her colleagues compared the genetic records of dogs and humans from the late Pleistocene, when the earth was covered extensively by ice, to seek clues about the ways both species dispersed throughout the world.

Their findings suggested that by around 23,000 years ago, humans had already domesticated dogs in Siberia—and that the first people to arrive in North America from Siberia brought their canines.

Food scraps, offered to wolves, could have been a bridge between two worlds.

In the harsh climate of the Last Glacial Maximum, Perri and her colleagues argue, Beringia in Northeastern Siberia provided a relatively warm yet isolated haven. On this exposed landmass, the ecological niches of humans and wolves came together for thousands of years, a potential driver for domestication. “We know that it’s a really nasty time period climatically. And that they’ve essentially found this kind of refugium,” Perri says.

And a cold climate could explain other aspects of the human-wolf connection. These species shared territory and prey, meaning potentially lethal competition for food. But a study out this year offers a hypothesis that could resolve this problem: In harsh winters, humans would have been eating a heavily animal-based, high-protein diet—one their bodies were not adapted to consume.

As a result, people likely had food left over. These scraps, if fed to the wolves, would have been a bridge between the two worlds.

Indeed, food plays a central role in understanding how canine domestication happened. The dominant theory suggests wolves scavenged food—and perhaps feces—from early forager settlements. Over time, humans welcomed animals that showed less fear and aggression.

A competing theory, which has risen in prominence in recent years, is that humans took wolf pups and raised them in their camps. Some would grow up and return to the wild, while others would remain to be fed and bred by humans.

“In a certain way, it’s a spectrum,” says Mietje Germonpré, a paleontologist and archaeozoologist at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences. “In both cases, the wolves were eating prey that was killed by humans.”

Both parties benefited as the partnership grew. Wolves had a steady supply of food, for instance. For humans, the animals offered an early hunting technology, reducing the risk and energy required to acquire food—energy that could be spent on other tasks and the general advancement of human culture.

Desirable yet dangerous prey animals, such as wild boar, would have gained prominence as a food source. Dogs could extend our species’ senses by seeking out prey or helping to track wounded animals.

This advance could have played a part in the development of certain hunting methods such as poison arrows, says James Serpell, a professor of ethics and animal welfare at the University of Pennsylvania. If a poisoned animal fled a long distance before it died, tracking it would be tricky. “If you’ve got a dog with a dog’s nose, then you’re ahead of the game,” he says.

Dogs would have helped humans to domesticate animals like sheep, or goats, with their natural herding ability too. “I think this could have been a major transitional process in the domestication of some of these ungulates,” Serpell says.

And, as a living, breathing, renewable technology, dogs have been put to use in a range of applications. Dogs are “a Swiss Army knife,” as Perri puts it. “A dog can essentially be whatever you want it to be.”

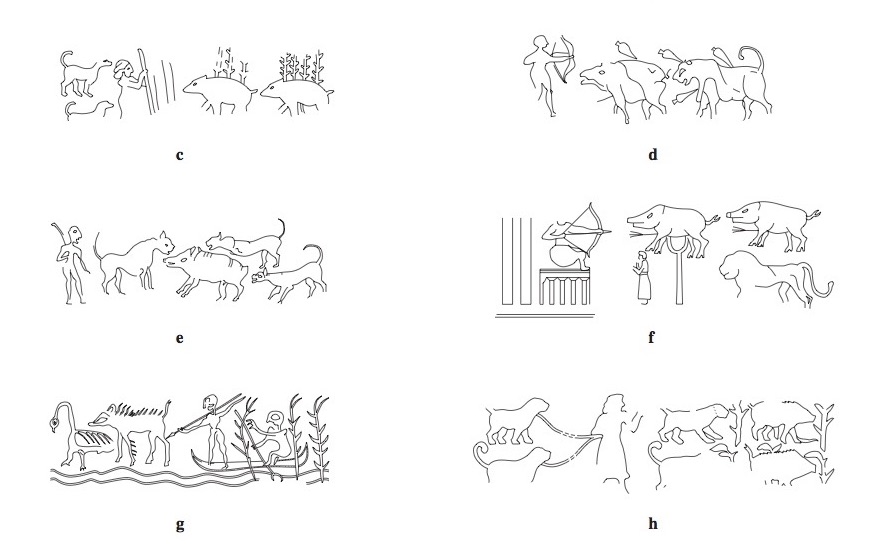

By 7,000 years ago, when ancient Mesopotamians discarded canine bones in Tell Surezha, domesticated dogs were appearing the world over. In a study published online in November of last year in the Journal of Field Archaeology, Price and his team explored extensive “canine economies” that existed in the ancient world around the Mediterranean and Near East, and the many roles dogs played, from the magical to the macabre.

Dogs began to feature in combat, for example. Ancient texts suggest that 2,400 years ago in Mesopotamia, high-status citizens and city rulers brought dogs to hunt boar. Around 2100 B.C., the third Sumerian dynasty had dedicated kennels and dog handlers, and raised and trained dogs as part of their army. By 2000 B.C., war bands on the Russian steppes ritually killed and consumed dogs as a rite of passage.

Dogs were also associated with the supernatural. The Romans, for example, believed they could transfer illness into dogs or sacrifice canines to ensure fertility.

The Hittites, who lived in modern-day Turkey between 1700 B.C. and 1200 B.C., used adult dogs as guards and hunting companions. Yet they brutally sacrificed puppies, using flesh, bone, and feces in ceremonial acts.

The dog “tends to be the most prominent animal that we find that has these multidimensional aspects to it,” says Brandi Bethke, an Oklahoma Archaeological Survey archaeologist at the University of Oklahoma. This versatility extends beyond the grave: A dog loved as a pet in life may have gained use in some ritual aspect after death, and a canine used for labor may have later become food.

What we consume is often an artifact of culture. Specific practices that may be taboo in some communities can be linked to the spiritual realm in others, with diverse, complex meanings for different societies. “In some cases, [dogs] being an unusual food is part of the reason that rituals were powerful,” explains Nerissa Russell, a zooarchaeologist at Cornell University.

Understanding that dogs may have been used in several ways, even within one society, is allowing archaeologists to have more subtle and diverse interpretations. “Being able to bring in all these different points of research is really helping us better interpret dogs,” Bethke says, referring to Price’s study as an example.

The building at Tell Surezha containing the bones Price analyzed was possibly a site of ritual feasting and ceremony. An emerging higher social class may have eaten dogs and wolves in that space to draw on the canine’s magical associations, reaffirming the standing of these new elites in the social hierarchy. Or young soldiers may have feasted on the animals before heading to battle.

Price documented several other examples of cynophagy. At Acemhöyük, a major urban center in Bronze Age Turkey, researchers found 461 bone specimens from dogs close to the city center. The evidence suggests humans regularly skinned, butchered, and ate dogs. And in Mycenae in Greece, the cuts on dog bones from around 1300 B.C. suggest butchery and decapitation, which may be linked to both ritual and everyday consumption.

Commenting on this work, Russell notes that “dogs have fulfilled just about every possible human-animal relationship.” She suspects people outside of zooarchaeology sometimes overlook this point because they are accustomed to categorizing species into specific roles—often informed by their own cultural norms. “So, dogs for us are only pets,” she says, thinking in a Western framework. “And it’s not always true.”

Price adds that it’s important to get past this bias to better understand the past. “I think taking it more seriously will allow us to have a more complicated, but maybe more sober, analysis of this fascinating relationship between dogs and humans,” he says.

The arrival of agriculture, for example, was a pivotal moment for canine-human interactions. Perri’s research has revealed that in hunter-gatherer societies, dogs received elaborate burials akin to humans, with some even buried with grave goods.

But with the general shift to farming, when hunting assistance became less critical, burial evidence suggests canines were no longer highly valued as group members. They were increasingly seen as pests, begging for scraps of food and picking fights with small children.

“And then you start seeing dogs being used in all sorts of ways,” Perri says, including widespread ritual sacrifice in cultures around the world. “Once we have ethnographic and historic records coming in, we do see over and over across the board that dogs seem to be very closely tied into ideas of cleanliness, purity, death.”

“There’s a million things a dog can do for you … unlike any other domesticated animal,” says zooarchaeologist Angela Perri.

As scientists look more deeply into changes written in dogs’ genomes, they can better understand shifts in human societies too. Last year, a study published in Science analyzed 27 ancient dog genomes to try to pin down the gene flow between dogs and wolves. By 11,000 years ago, the authors concluded, dogs had diversified wildly and established five major genetic lines.

When the researchers cross-checked the genomes of humans and dogs living in similar time periods and cultures, they found certain shifts in the dog genomes closely mirrored historical human events. For example, after the arrival of Neolithic farmers from the Levant, a region along the Eastern Mediterranean, into Europe some 8,000 years ago, dogs started to show increasing copies of a gene involved with the digestion of starch.

Not every notable genetic change lined up with human activities, though. During the Bronze Age, nomadic herders from the steppes of modern-day Russia and Ukraine expanded into Europe and Asia, leaving a strong signature in human genomes.

But the researchers found no equivalent major change in dogs from this period. This example suggests three possibilities: Some humans traveled without canines, dogs migrated independently of humans, or disparate human cultures had started to use dogs for cultural and economic exchange—trading these animals.

Humanity’s relationship with canines has likely been multifaceted from the very beginning. Wolves, after all, have long been seen as dangerous competitors and predators.

At Předmostí in the Czech Republic, remains indicate that humans modified wolf skulls about 30,000 years ago in a way that “could be interpreted as the consequence of rituals,” Germonpré says. Cut marks on wolf bones suggest people also ate wolf meat, alongside mammoth, she adds.

And when wolves joined the human pack in the icy winds of Siberia, for instance, they likely helped with transport, as alarm systems for roving predators, to clean up camps of spare food, and, when times were lean, to become it.

But humans probably also used canines as bed warmers, Perri notes, and—as many dog owners would attest is perhaps the most fundamental, enduring role—for companionship.

Correction: July 6, 2021

Previously, the article suggested that hundreds of dog bones at the Mycenae site had cuts that showed butchery and decapitation. Though hundreds of dog bones were indeed present, only a fraction had such markings.