Can the Hunt for Skeletons Help Heal a Nation’s Wounds?

Please note that this article includes images of human remains.

The abandoned Nicosia airport in Cyprus is a strange place for an anthropology lab. But there I was—at the end of a humid spring day in 2017—looking at about 30 skeletons carefully laid out on rows of wooden tables. Clothes and personal effects, sealed in transparent bags, dispelled any notion that the bodies might be ancient. The plastic sandals retained their shape. The bright orange, blue, and yellow hues felt so specific to the 1970s. There were tattered high heels, neon buttons from children’s shirts, and shreds of paisley fabric with rust-colored stains.

The remains had been exhumed in 2016 from a mass grave near the port city of Famagusta, also known by its Turkish name Mağusa. In August 1974, Greek Cypriot paramilitary fighters killed more than 100 Turkish Cypriots, many of them women and children, in the villages of Maratha (Turkish name: Muratağa), Sandalaris (Sandallar), and Aloa (Atlılar). When U.N. security forces were able to enter the area a couple weeks later, they made a Sisyphean attempt to identify, count, and re-bury the dead whose remains had been left at a dump. The Associated Press at the time described a horrifying scene where bodies “were so battered and decomposed that they crumbled to pieces when soldiers lifted them from the garbage with shovels.”

Cyprus, an island nation in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, has been divided by a U.N. buffer zone ever since 1974. After centuries of living under foreign rulers—from the Egyptians and Assyrians to the Ottomans and the British—the island gained independence in 1960 with a power-sharing arrangement between the Greek Cypriot majority and the Turkish Cypriot minority. But long-simmering disputes between the two communities erupted in violence from late 1963 into 1964. Then, in 1974, after a short-lived Greece-backed coup, Turkey invaded Cyprus. By the end of that especially bloody summer, Turkish troops occupied the northern third of the island.

When I visited the island last May, few people I spoke with were hopeful for an imminent reunification. The latest round of peace talks was floundering, and the effort ultimately collapsed in July 2017 over several of the usual sticking points, including sovereignty, property, and the presence of Turkish troops. The unresolved issue of missing persons used to be a major point of contention as well, one that personally affected many families on the small island, which has a population of just over 1 million.

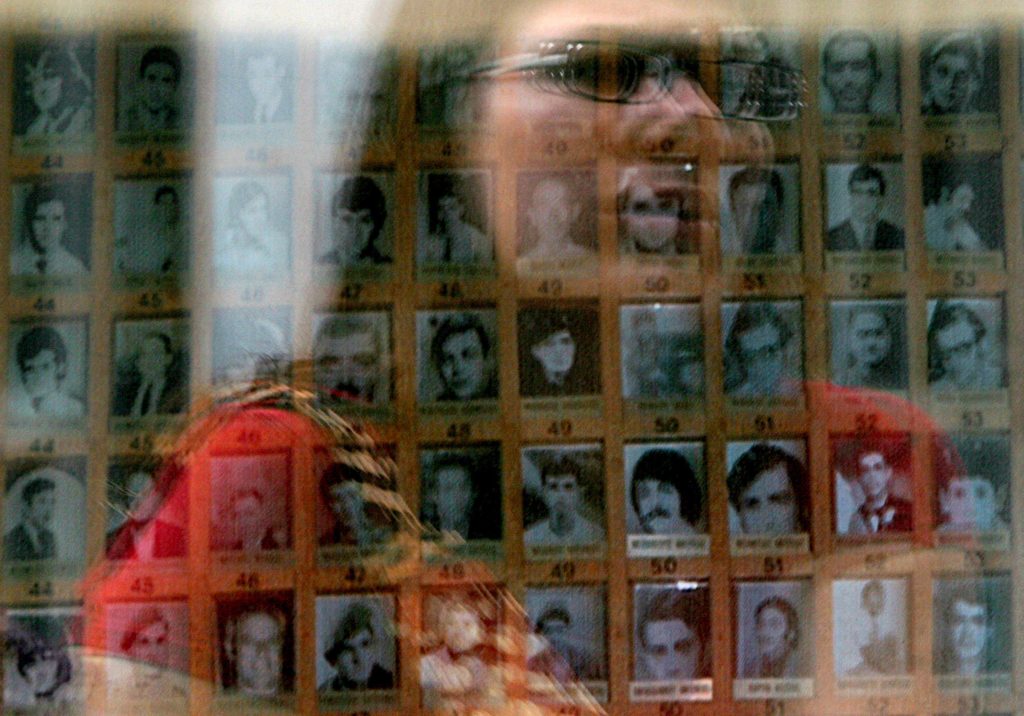

About 500 Turkish Cypriots and 1,500 Greek Cypriots disappeared during the two periods of violence. Some victims were taken from their homes; others were executed during military operations. Bodies were dumped in wells, shallow pits, and mass graves across the island. Many families never got a chance to properly bury their relatives. Others were left totally in the dark as to what had happened to their loved ones.

But over the last decade, the two sides have been working together to confront this one aspect of their shared history by finding and identifying the lost remains of their dead. As a rare example of collaboration in this sharply divided land, the Committee on Missing Persons in Cyprus (CMP) not only brings experts from both communities together but also provides much-needed hope for a unified future. Now, though, the stream of tips about where to find the remains of the missing is drying up, and people involved in the project have begun to worry that, someday in the not-too-distant future, their work may trickle to a stop.

In 2006, the CMP, which is a U.N.-backed team of investigators, archaeologists, geneticists, and anthropologists, began exhuming bodies on both sides of the island. They act on tips that range from eyewitness testimony to rumors and reports of overheard conversations. There is hardly a typical excavation for the CMP. Their archaeologists have dug inside limestone kilns, beneath new swimming pools, and in riverbeds, open fields, and wells more than a hundred feet deep. Sometimes they expect to find 80 people—and at other times, just one.

At any given time, the CMP might have eight active excavations. The group has exhumed 1,217 bodies and identified 855 people as of December 31, 2017. The CMP likely owes its success to one of its most unique and controversial features: It has no judicial mandate. Thus its work is insulated from the tense political situation. Witnesses who are suspected of being perpetrators are not turned over to prosecutors. Families who come to collect the remains of their loved ones are told neither the cause of death nor the killer, even if both are known.

“The big problem a lot of investigations have is finding incentives for people to come forward with information,” Ian Hanson told me when I called him after my trip to Cyprus. Hanson is an archaeologist at Bournemouth University in the U.K. who has worked for the International Commission on Missing Persons, and he acted as a consultant to the CMP at the outset of the investigations. When I used the word “forensic” to describe the CMP’s work, Hanson quickly corrected me. In the strictest sense of the word, he said, “forensic” means “relating to courts of law.”

In places like Bosnia and Herzegovina, investigators can use their powers of arrest and interrogation to get information about the location of human remains, Hanson says; that country’s prosecutor’s office is spearheading the search for the 8,000 people still missing since the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s. In Cyprus, confidentiality and immunity are meant to incentivize witnesses.

A Turkish Cypriot archaeologist, Müge Şevketoğlu, first told me about the CMP while I was interviewing her for a story about the difficulties of doing research in her homeland. The Turkish Cypriot–controlled northern part of the island, considered occupied territory by most of the world, is politically isolated. Her students have few professional options in the north to do archaeology, she said—unless they want to work for the CMP. Eager to learn more about this unique organization, I contacted Florian von König, the permanent secretary of the CMP, and he agreed to spend a day showing me around.

A couple months later, when the day came to meet von König, I entered the buffer zone from the Greek Cypriot side of Nicosia, also known as Lefkosia, the island’s divided capital. I showed the guards my passport at the crossing and entered Markou Drakou Street, where Cyprus’s contradictions are laid bare. This stretch of neutral territory is both cheerful and militarized. Members of both communities can have coffee or take salsa-dancing classes together at the Home for Cooperation. They can enroll in German language courses at the Goethe-Institut Zypern. The street is lined with palms and oleanders, but there is also ample barbed wire and there are signs that prohibit taking photos. Walking toward the other side of the checkpoint, I immediately noticed a billboard that delineates the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus FOREVER.” U.N. peacekeepers, whose mission has the ignominious distinction of being one of the longest of its kind, are headquartered on this street at the once-glamorous 1940s Ledra Palace Hotel.

Von König was waiting for me outside the hotel, looking relaxed in a blue polo shirt and khakis, to bring me to see two excavations in progress. He drove us out of the buffer zone in a white Jeep, past another passport check, and then east across the Mesaoria plain in the Turkish Cypriot part of the island. This fertile plain is a vast stretch of farmland, enclosed by the jagged spine of mountains that runs along the north coast. Clashes and killings took place here during the summer of 1974 after Turkish troops swept over the mountains, von König said, and, as a result, many of the CMP’s excavations have been conducted in this prairie-like expanse. “This place is littered with bodies,” he noted matter-of-factly. He pointed out the site of a former rail station where the group recently located wells, now covered by the highway, that are suspected to hold human remains.

After driving for nearly an hour, and getting lost in some poorly marked streets in the outskirts of Famagusta near the coast, we reached our first stop, a dig site in a cereal field that used to be an orange grove. Here, in 1974, a woman stepped on the corpse of a Greek Cypriot in civilian clothes. His body was never recovered, but thanks to the woman’s tip, more than 40 years later, a CMP team was on site looking for his remains. The archaeologists might have been mistaken for a construction crew if not for their white, full-body forensic-style suits, typically worn only at sites that might contain hazardous waste, such as asbestos or animal carcasses.

Irini Papadopoulou, the Greek Cypriot archaeologist in charge of writing up the report for the excavation, told me that she didn’t think they were likely to find a neat grave with an articulated skeleton. If the man’s body was here, his bones were probably disturbed by now from years of the soil being churned up. In the rectangular roadside trench the crew had carved out over the last two weeks, the jumbled layers of dirt and trash were barely distinguishable. In one corner, the earth had started to yield a few teeth and very small bone fragments. At that point, the archaeologists switched to finer picks for manual excavation.

“As time passes the good information is starting to dry up, so you don’t have a chance to recover so many missing persons,” Papadopoulou said. “But I still have hope.” She said it’s difficult not to be personally moved by the cases. “If the people you are looking for had parents who were looking for them—I think that’s the thing that most affected me.” Our conversation was cut short when a member of her team found a piece of a skull. Months later when I emailed Papadopoulou, she was still waiting for the lab results to know if the mixed-up bone fragments and teeth had been identified.

In the decades between the violence of the 1960s and ’70s and the start of the excavations, the issue of missing persons was treated with silence. On the Greek Cypriot side, some believed their missing relatives were still alive in Turkish detention centers, and many were not even aware of the existence of Turkish Cypriot missing persons, political scientist Iosif Kovras wrote in his book Grassroots Activism and the Evolution of Transitional Justice: The Families of the Disappeared.

By compiling an exhaustive list of missing persons, and publishing statistics on its findings, the CMP has uncovered a history of killings on both sides of the island. Yet, for some, the mission does not go far enough in telling the truth about what happened. Truth Now, a nongovernmental Greek Cypriot organization, has been calling for the CMP to expand into a full-fledged truth commission that would shed light on the circumstances of death for the missing. “We want to know what happened so that the families’ right to know is satisfied,” says Achilleas Demetriades, a lawyer with the group. “Nobody’s taking a bold stance about it. Nobody seems to want to shake up the system.”

Families’ right to the truth and the state’s duty to investigate and prosecute political disappearances are considered core principles of human rights today. The CMP’s mandate, which contradicts those core tenets, was outlined in 1981, before those international norms were established. (The CMP was dormant for decades; the two sides were initially unable to agree on a list of the missing persons, and the state of political negotiations made it untenable to start excavations.) Paradoxically, this outdated mandate has become the key to the CMP’s success.

Kovras told me he thinks that a family of a missing person would have legal recourse in Cyprus to challenge the mandate, and to get more information if they went to a court and presented the evidence they were given from a CMP exhumation. However, families in Cyprus have not attempted to initiate criminal investigations because they don’t want to jeopardize the recovery of remains by deterring potential witnesses; they don’t want to deny other families the right to bury their loved ones, according to Kovras’ assessment. “There is a very fine balance between addressing the humanitarian needs of the victims and getting justice,” Kovras says.

Some have pursued legal options with the European Court of Human Rights. In a landmark ruling in 2014, the court ordered Turkey to pay 90 million euros to the families of those who died or went missing during the invasion of Cyprus. Turkey has refused to pay the compensation.

For now, compromise seems necessary to make progress where political standstill is the norm. The limited scope of the project, von König says, is “very simply a reflection of the political realities when the CMP was founded and the realities that continue to this day.” The conflict, though no longer violent, is ongoing, and without reunification, he adds, he couldn’t imagine prosecutions taking place.

After leaving the site in Famagusta, von König and I headed back west toward Nicosia. Just before we reached the capital’s suburbs, we pulled off the highway at Minareliköy, or Neo Chorio Kythreas. (Many towns in Cyprus have both Turkish and Greek names, which, perhaps unsurprisingly, are also subject to political controversy.) The village used to have a mixed population. After the fighting in 1963–64, the Turkish Cypriot inhabitants, like many others across the island, withdrew to the safety of ethnic enclaves. The Greek Cypriots who remained were then pushed out by the 1974 invasion—during which, a couple living in the town was killed and buried in their backyard.

We drove past a vandalized Greek Orthodox cemetery and stopped at the site of the Greek Cypriot couple’s house, now an olive grove that lies adjacent to a Turkish military installation. There were just two archaeologists on site—the minimum number of team members required per excavation, as each CMP dig must include archaeologists from both sides of the island. They were watching for signs of a grave in the dirt as they directed a workman to scoop trenches between the trees with a mini-excavator. One wore a balaclava, decorated with a skull, to keep the rising brown dust out of his mouth.

In 2015, the CMP, working with witness tips, uncovered the foundation of the deceased couple’s house. They even found a piece of marble that the son of the slain couple recognized from the home’s décor. But there were no bodies. A new witness tipoff indicated that the archaeologists should start digging farther south in the backyard, so this year they expanded their work.

The Turkish Cypriot team leader here, Güliz Bürüncük, showed me the place where they found the body of the man in front of a tree in a manually dug grave just a foot and a half below the soil’s surface. They had assumed that the couple was buried together, but the woman was still nowhere to be found, and the archaeologists were nearing the end of their planned excavation area. “I’m worried about where his wife is,” Bürüncük said. “How will we say we found this guy but we didn’t find his wife?”

Living witnesses are the best sources of information on hidden graves across Cyprus—but as time passes, fewer are available to give testimony. As the group exhausts its most reliable tips, the number of individuals exhumed per year is going down significantly, von König said. A recent spike was due only to excavations of the mass grave near Famagusta. “There are probably sites that nobody knows about anymore.”

Von König said it would be premature to talk about the end of the CMP, though the long-term outlook of the project is clear: “It requires more and more effort to find the next set of remains, and then it becomes a question of resources: How long do you have to invest more and more money into less and less results?” On the other hand, can Cypriots ever declare the project finished if the number of missing never shrinks to zero? He imagined the effort to recover the missing could remain open-ended, somewhat like the U.S. military’s program to account for its missing war dead overseas.

The prospect of the CMP’s work dwindling, with no political solution for the island in sight, weighs heavily on those involved for another reason as well. It’s rare for Greek and Turkish Cypriots in any field to work together in an official capacity. The CMP is praised across Cyprus—by archaeologists, politicians, and laypeople alike—as a model of bicommunal collaboration. (Perhaps its only rival is Nicosia’s common sewage system.) “Virtually all Greek Cypriots missing are located in the north, and a large majority of Turkish are in the south,” von König said, reflecting on the project’s success when we got in the car to head back to Nicosia. “There’s a built-in reciprocity. One of the reasons it has worked is that they each have to look for the other’s missing.”

After a short drive, we ended up, like everything the CMP finds in the field, at the Nicosia airport. U.N. soldiers with blue berets saluted as we drove through a maze of concrete barriers at the guarded entrance. The complex, which has been occupied by the U.N. since they took it over in 1974, is a rare oasis in the middle of Nicosia’s untidy sprawl. With a golf course and an Olympic-size swimming pool, this part of the buffer zone would almost feel like a country club for diplomats were it not for the hangars and other airport facilities with old signs and broken windows, frozen in time.

In the anthropology lab, among the skeletons from the mass grave, I wandered over to Theodora Eleftheriou, an anthropologist with a white coat and a clipboard. She was reviewing a colleague’s analysis of a skeleton. She lifted the skull so that I could see the back of it, shattered by a bullet. A photograph showed how the body had been found, facedown.

Eleftheriou and her colleagues have learned how to walk a delicate line between giving families useful information and following the CMP’s mandate. The anthropologists can show the family injuries and signs of trauma on the bones, but they cannot officially speculate on the cause of death. They cannot say if the person suffered or was tortured. They cannot say how investigators were led to the body.

“The difficult part is to make them trust you,” Eleftheriou said. “You need to trust yourself that you’re sure about what you’re saying. You need to find a way to present yourself. So the family, from one point of view, can see you as a scientist so they can trust you. But from the other point of view, they can see this person who understands and shares their feelings. The whole situation is complicated.” With little other information, sometimes seeing the mark of a gunshot, perhaps an indicator of a quick death, can be a comfort for family members, Eleftheriou said.

Just steps from the lab is the room where families come to collect their loved ones’ remains. The team just had a viewing earlier that day. “When you have a natural death, all the stages of grief are more automatic,” says Lisa Zamba, one of the CMP’s full-time trauma psychologists. “When you lose someone and you actually see the dead body, it’s more easy to understand.” In contrast, the families of missing persons have to restart this process after 40 years. They only take home a lightweight box of bones. “They have to do a lot of work with themselves to accept the situation.”

Some don’t fare so well in this unnatural grief process. Others eventually find acceptance, says Zamba. A few even want to get to know victims’ families from the other community, and the psychologists are happy to arrange meetings. “We try to bring them together to understand that the pain is the same.”