Coronavirus and Coping With Death

While sheltering in place in California during the COVID-19 pandemic, I have been spending a lot of time thinking about my graduation day—but not because it was particularly uplifting. On that day, I coincidentally and extraordinarily had a distressing run-in with a dead body.

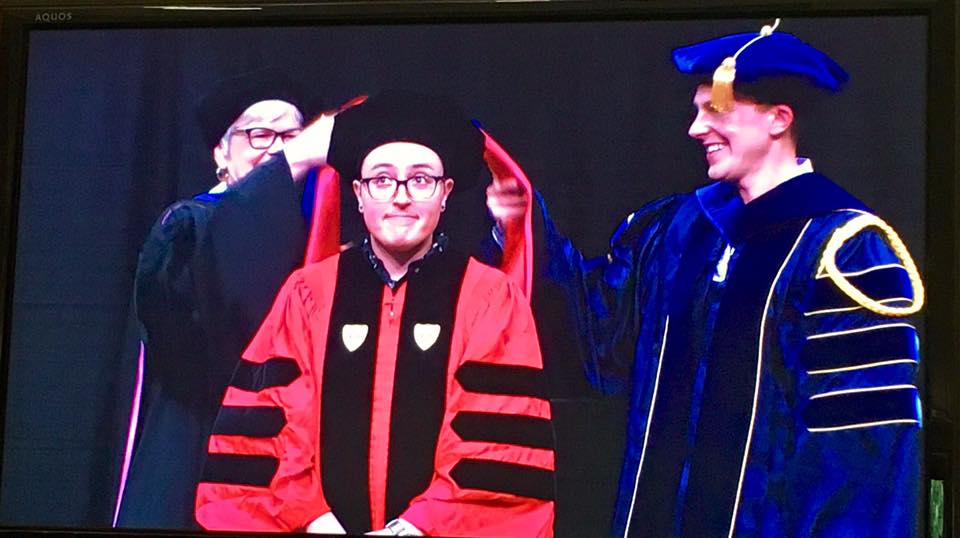

I received my Ph.D. from Boston University in May 2017. The day of the graduation ceremony, I went for an afternoon jog along the Charles River to deal with the jitters of having to walk across a stage wearing a silly floppy hat in front of hundreds of strangers. In one direction, the run was uneventful. On the way back, though, I happened to glance out over the water and stumbled to a halt. There was a human head and shoulders just visible above the surface of the water, facedown, and about 10 meters from the riverbank. I kept staring. I saw no movement. Within minutes, I was on the phone to 911 dispatch, wading chest-deep into the river to make sure this was not a living person in need of assistance. It was not.

Thankfully, Boston is a city full of hospitals and medical schools, and a pair of doctors also happened to jog by as I started calling out for help. They splashed into the water and helped me get the body to the riverbank. Together, we waited for an emergency medical team and the police to arrive. I gave my statement and then squished my way back to the university for a hurried but very thorough shower. I put on my graduation robe and the silly floppy hat, and walked across the stage.

I thought I would be traumatized by this experience. It was deeply upsetting, and a far too intimate encounter with death. But the expected trauma never came. I had no nightmares, no tears. I have always wondered if it was because I am an archaeologist, specializing in identifying, collecting, and curating animal remains. I’ve had plenty of dealings with the recently dead (though in the form of animals like deer and coyotes, not humans), and have spent a lot of time thinking about long-dead people and populations.

Can anthropologists provide others with context, comfort, or ways to cope? Does an archaeological or anthropological background change the way we think about death and crisis?

By its very nature, archaeology provides the distance of time between the living and the dead. In my research, I study people who have been dead for 50,000 years or more. In my own experience in the Charles River, the individual was a stranger, and though I was saddened by the reality of his death, I felt that same sense of academic distance.

But the unfocused grief and anxiety of a global pandemic and its deaths is a completely new experience. Seeking understanding, and perhaps a way to help others, I have turned again to anthropology. I reached out to colleagues and friends on social media, hoping for perspective. Their responses were varied, insightful, and deeply meaningful.

Not all archaeologists are the same, of course. As one friend, archaeologist Catherine Scott of Brandeis University, wrote, “The ways and contexts in which we do archaeology are so diverse that I don’t think everyone is likely to be shaped in the same way by it.” Those who study bioarchaeology confront death in a far more explicit way than those who do not study human remains, for example.

Several colleagues wrote that they, too, tend to see the lives and deaths of the people they study in the abstract. Boston University zooarchaeologist Catherine West shared with me: “Being an archaeologist has taught me very little about death. I had to experience it firsthand to understand the intimacy and power of it.” She went on to say that she hadn’t yet considered the pandemic academically because she was focused instead on getting through each day and keeping her family content.

Many of those who responded expressed a fear of what things will look like once the spread of COVID-19 has been halted. When archaeologists look back through time, we can see both the “before” and the “after.” In real time, we cannot see the “after.” I realized that this was the root of many of my own anxious thoughts, and I suspect that is true for most of us. Describing or intellectualizing this feeling provides, for me at least, some small sense of increased control.

One graduate school friend, Laura Heath-Stout, a Mesoamerican specialist at Houston’s Rice University, wrote that it helped her to know that the common narrative about the “collapse” of civilization is false. Over and over again, the archaeological record shows that through terrible upheavals, colonizations, wars, and epidemics, cultures and communities are incredibly resilient. Humans are a persistent species.

Another friend, historical archaeologist Laura Masur of The Catholic University of America, contributed the perspective that those who live in modern, developed nations or regions are privileged to expect to lead long lives because of modern sanitation and health care. Previous epidemics, like the 14th-century Black Death, or even the much more recent 1918 flu pandemic, occurred before many of the advancements that treat and prevent disease today. Now many have access to new and developing medical information that travels in the blink of an eye, and we are learning how to keep ourselves and our loved ones safe.

Anthropology, above all, is about understanding human lives. How will this experience shape the stories we tell? How will the shared experience of this pandemic stamp itself onto us, to be seen in the future by those looking into the past?

A final thought from colleague Hilary Leathem, a doctoral candidate at the University of Chicago: This event is globally inherited, something that is part of humanity’s history. As she wrote to me on Twitter: “It possesses everyone, and we possess it.”

We all share the emotional and intellectual labor of coping with a global crisis. Anthropologists can help, whether we create context from history or whether we just get through one day at a time, keeping each other safe.