Diamond Mine Threatens Stone Age Artifacts

Researchers are panicking as a Stone Age archaeological site in South Africa called Canteen Kopje is facing demolition by diamond mining. Miners have already started to clear the site, which is about 10 acres in size. “For us that would take years to explore; but for the miners with their huge diggers it’s an afternoon’s work,” says Michael Chazan, an anthropologist at the University of Toronto who does research at the site and is involved with a local field school there.

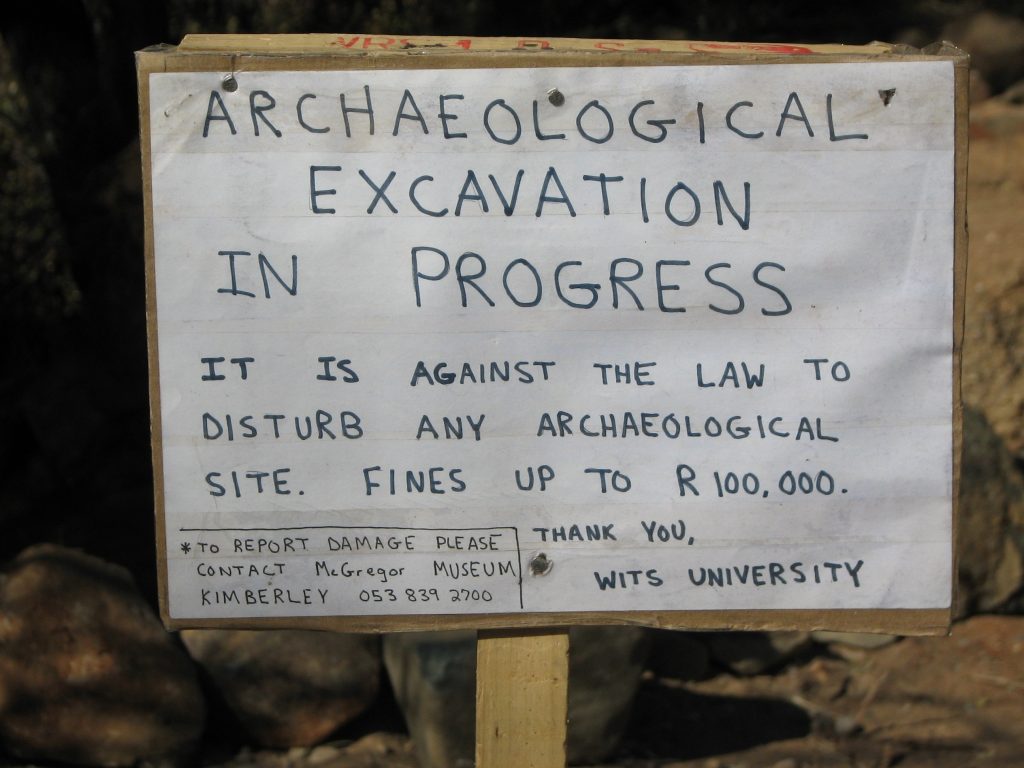

The area has been protected as a South African heritage site since 1948. The local McGregor Museum notes that miners tried to take over the area in the 1990s as well, but the site was preserved. Today’s threat appears to be more acute.

David Morris, head of archaeology at that museum and a professor at nearby Sol Plaatje University in Kimberley, says miners dug an 80-meter by 80-meter hole, up to 6 meters deep, on March 18. “It’s like someone has torn pages out of the history book,” he says. “In the wake of the machines, artifacts are strewn across the surface.” Archaeologists managed to get an interim court interdict declaring the mining illegal as of March 19, and for the moment mining work has stopped. That should last until early April, says Morris, who adds that a small team of lawyers is working on a more permanent solution.

“It’s horrifying. This is a major, known, documented resource and it will be lost forever [if mining resumes],” says Chazan.

Canteen Kopje is a small hill outside the town of Barkly West in the Northern Cape province of South Africa, thought to have once been an island of the Vaal River. “It was probably rich with animals and attracted a lot of people,” says Chazan, who says there are tens of millions of artifacts in the hill dating back to the Earlier Stone Age some 2.3 million years ago.

These include examples of the oldest known tools—simple chipped river cobblestones called Oldowan tools. The most famous find from Canteen Kopje is a skull, discovered in 1929, that was interpreted at the time to be a large-brained early ancestor of modern humans (it was later reclassified as a more modern skull). Unpublished work has also found evidence of glittery iron ores being transported more than 100 kilometers to the site some 300,000–500,000 years ago, perhaps for use as make-up pigments during ritual dances. Ironically, the site is also historically significant as part of South Africa’s diamond rush. In 1869, European miners flocked to the Vaal River looking for gems—the famous 83.5 carat Star of South Africa was found close to this river’s banks. It was a diamond prospector who discovered the 1929 skull.

Today’s heritage site represents about 20 percent of the original archaeologically rich site. “The rest has been mined away,” says Morris. Only a small fraction of the remaining protected site has been systematically investigated, he says.

There are other early Stone Age sites in South Africa, notes Chazan. But, he says, “What’s under attack is not just the place. It’s horrific that research from a South African university is being stepped on.” He notes that at least two active, local research projects won’t be able to proceed if the mining continues.

Other South African archaeological sites have been threatened before. Development of the iron-mining town of Kathu threatened an early Stone Age site. “There we were able to reach a working arrangement,” says Chazan. And a coal-mining operation was planned near the boundary of Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape in South Africa, a United Nations World Heritage Site with rock art up to 10,000 years old. “Mining is becoming a significant threat of heritage sites, not just in South Africa, but throughout the world,” says the Association of Southern African Professional Archaeologists, which has joined forces to help preserve Canteen Kopje.

“We’re a pretty realistic group of people. We know that development happens. We know that mining happens. And we benefit from mining—it exposes the sites,” says Chazan. “But in this case there have been no serious consultations. We’re basically getting steamrolled.” Chazan and colleagues in South Africa are encouraging archaeologists and anyone else concerned to write to the minister of arts and culture in protest. “If known, registered sites can be overwhelmed by mining it basically puts all South African heritage sites in danger.”

Editors’ Note:

As of the time of publication, the organization responsible for protecting the site, the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA), could not be reached for comment.