Why the Camp Grant Massacre Matters Today

Before dawn broke on April 30, 1871, a vigilante posse began killing Apache people.

The victims were members of the Aravaipa and Pinal bands who were peacefully settled under the protection of the U.S. Army. But ongoing raiding by Chiricahua Apaches across the Arizona Territory had inflamed Tucson’s leaders. The Tucsonans gathered a force, with support from Tohono O’odham allies. The vigilantes marched through the desert night. By sunrise, more than 100 Apaches—mostly women, children, and the elderly—were slaughtered. The attackers took some 30 Apache children as slaves.

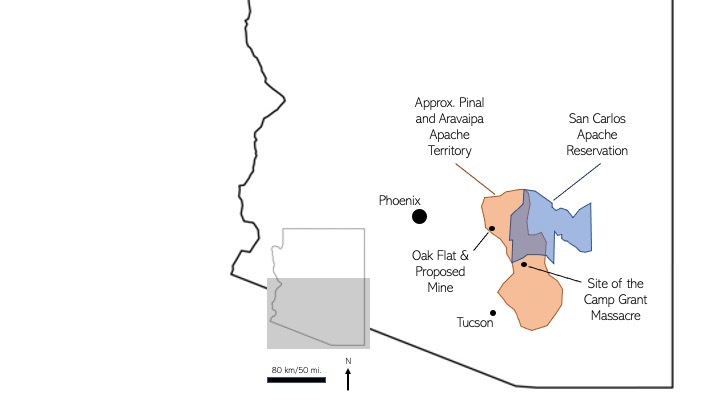

That massacre unfolded 150 years ago today. It is nearly forgotten as a collective memory—rarely memorialized and barely known. Yet, the massacre’s aftereffects are entirely present. Because of this violence, Pinal and Aravaipa people fled their homeland and retreated to lands later designated as the San Carlos Apache Reservation. A vital piece of their historic territory is now threatened by the proposed development of a gigantic copper mine.

The Camp Grant Massacre is a phantom in Tucson’s history, with both a haunting presence and absence.

I was born and raised in Tucson, yet I never learned about the Camp Grant Massacre. I only came across these horrifying events while participating in a 2001 research project on the region’s history as a professional anthropologist.

As I dug deeper into this story, I learned that mementos of the massacre dotted the landscape of my childhood. My elementary school and the streets that surrounded it, along with my favorite hiking spot, were all named after the massacre’s ringleaders. I came to see the massacre as a phantom in Tucson’s history, with both a haunting presence and absence.

Even Apaches can be reluctant to speak of the Camp Grant Massacre. This is partly due to cultural prohibitions against talking about the dead. It is also partly a mechanism for survival—to not dwell on such horrors.

But during my research, Apache elders did speak. I think they felt that to forget would be an injustice to the victims and an acquittal of the perpetrators. More importantly, they understood that the lives of their people were still being undone by the massacre.

The ongoing impact of that massacre is now centered on the battle over the fate of Oak Flat—an area larger than 7 square miles, now in the Tonto National Forest, about 65 miles east of Phoenix and a critical part of Apache traditional territory—that might be turned into one of the world’s largest copper mines.

Following the massacre, the Aravaipa and Pinal Apache survivors regrouped on what would become the San Carlos Apache Reservation to the north, rightly frightened to return home. Life on the reservation, however, proved exhausting. Some Apaches today refer to the early reservation as a “concentration camp” because they were rarely allowed to leave the reservation’s confines, they suffered from constant food shortages, and Apaches from different bands were forced to live together.

The small reservation kept shrinking as its edges were peeled off for American migrants to take up farming, ranching, and especially mining. As early as 1870, an Army colonel wrote that when Americans discover the extent of the mineral wealth underneath the Pinal Apache people’s land “there will be such a rush, the Indians will be ousted in a very short time.”

Anthropologist and Apache ally John Welch has documented that more than 380 Pinal Apache people were murdered between 1859 and 1874 during a focused campaign by the U.S. government and industry agents to remove Apache communities and make way for mines in the area that would become Oak Flat.

Fast forward to the early 2000s. The Anglo-Australian company Rio Tinto Group and its primary project partner, BHP, headquartered in Australia, have been working to develop a copper mine in Oak Flat, just west of the San Carlos Apache Reservation. The companies hope to extract 1.4 billion tons of ore and 40 billion pounds of copper through colossal underground caves; eventually, the entire area above it is expected to collapse, leaving a massive crater nearly 2 miles wide and 1,000 feet deep.

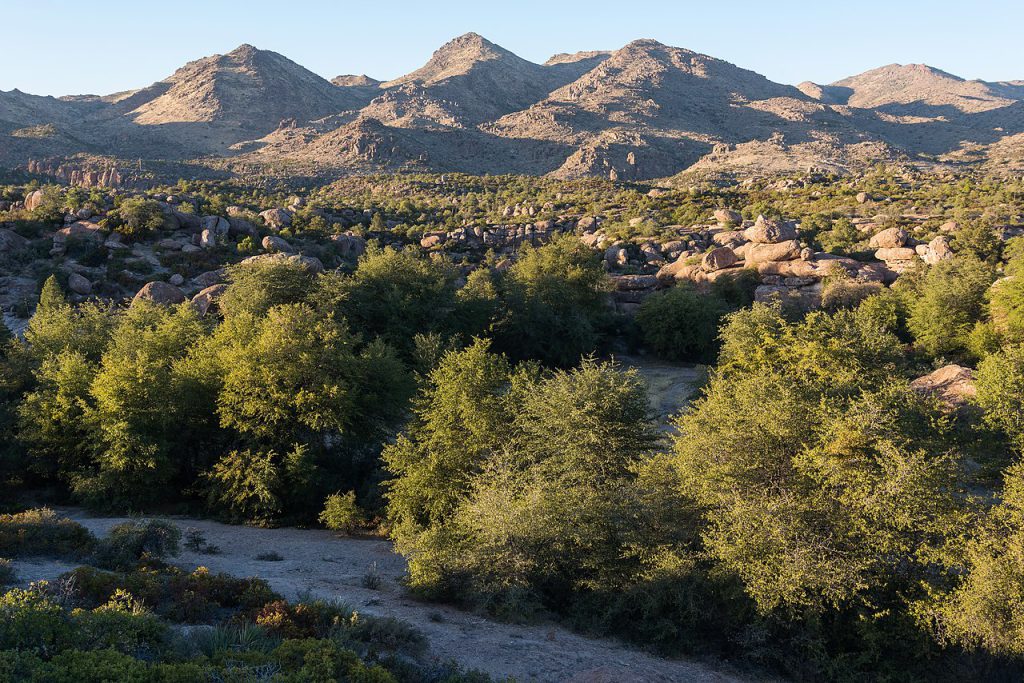

Apaches call this beloved area Chí’chil Biłdagoteel, which means “a broad flat of Emory oak trees.” In 2014–2015, I was part of a team to conduct an ethnohistoric study of the region, funded by Resolution Copper Mining (Rio Tinto and BHP) and supervised by the U.S. Forest Service, to provide information needed for compliance with the National Historic Preservation Act. Our study identified 377 Apache traditional cultural properties eligible for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places.

For untold generations, Apaches have gathered foods, medicines, and holy water in Chí’chil Biłdagoteel. In one place of power within the hills, they conduct ceremonies to usher girls into womanhood. Other important sites include trails, rock art panels, and the remnants of ancient villages and camps. This land contains stories that shape Apache identity and beckon Aravaipa and Pinal Apaches to continue their centuries-old relationships with place and tradition.

A handful of massacres of this continent’s First Peoples are seared into the American imagination—such as the murder of about 300 Lakota people at Wounded Knee in 1890—but many more violent events remain unknown, erased from nationalist histories. Today there is no monument or memorial to recall the Apache families murdered in the Arizona Territory in 1871.

For years, Apache tribal members and a coalition of allies have been fighting to stop the mine and preserve Chí’chil Biłdagoteel—a place that is still so vital to the hearts of the Apache people. The battle is being waged in the courts and through a bill: the Save Oak Flat Act, introduced to the current U.S. Congress this March.

It is perhaps a coincidence but perfectly fitting that this legislation is being discussed 150 years after Tucsonans perpetrated the Camp Grant Massacre to exile Apaches and take their land. At this moment, the rest of us in the U.S. need to decide whether we will allow the effects of the massacre to continue on, haunting us with their presence.

The Save Oak Flat Act needs broad support, now, both to protect Apache homelands and to put some of these phantoms to rest.

Editors’ Note: Chip Colwell is the editor-in-chief of SAPIENS. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not represent the opinions of the SAPIENS editors, Wenner-Gren Foundation, or University of Chicago Press.