Solving a Riddle About the Dawn of Art

On a Friday afternoon in September 2015, speleologist Iñaki Intxaurbe and I ventured into the heart of the Atxurra cave system in Spain’s Basque Country. Archaeologists had known about this labyrinthine underworld for over 80 years, but some of its caves still had surprises in store. After dragging ourselves through narrow corridors, called galleries, we finally arrived at a more comfortable place. We immediately noticed chambers near the ceiling and started climbing so we could look inside. Within minutes, I heard Intxaurbe shouting. I thought he was in danger, perhaps about to fall. But he was staring at the walls: “There is something engraved here!” When we inspected what he found, we were amazed to see the outlines of several bison figures.

Shocked, we glanced at each other—and then scanned the rest of the walls.

The area we were in was full of other high chambers. We kept exploring, finding more and more engravings and paintings of animals. After four hours—which felt like 10 minutes—we worked our way back out of the cave, totally exhausted. When we saw the rest of the survey team, they looked worried and asked us what had happened. They said our faces were very pale. For a moment, we were too stunned to even speak.

The area from northern Spain to southern France has long been considered the richest spot for Paleolithic cave art in the world. Across this broad region, around 150 cave art sites—dating from 10,000 to 40,000 years old—have been found since the first discovery in Altamira, Spain, in 1879. Yet, strangely, for a long time a near void on the cave art map existed in the Basque territory. Throughout the 20th century, researchers only found about a dozen caves in this area featuring ancient artwork.

I’ve been working as an archaeologist in the Basque region since 1998, and in 2011, I led a team to survey the area to see if we could fill in this gap. What we have discovered has surprised even us.

So far my team, as well as other groups of archaeologists and speleologists, have found an additional 20 cave art sites in Basque Country, which I discuss in my newly published article in the Journal of Anthropological Research. Together, our findings have nearly tripled the total known for the area. In 2015 alone, we found six new decorated caves, or ones that feature rock art images. In the rest of Europe, there is usually just one new find a year, if that; in the Pyrenees mountains, one of the hotspots of cave art, there hasn’t been a new find for decades.

Filling in the “void” has helped to resolve a long-standing riddle about early art and highlighted better ways to look for such finds. We now know that there are plenty more treasures to be found.

From the time that European caves were first explored in the 19th century, the low density of cave art findings in Basque Country has been hard to explain. Non-decorated habitation caves have been found fairly uniformly across Spain and France. And the geology of the region, including its caves, isn’t so different in Basque territory. Indeed, the area seems to have formed an important corridor between the European continent and the Iberian Peninsula. Clearly people passed through and lived in the area; were they less likely to make art?

When we started our intensive survey in 2011, we had better tools at our disposal than our predecessors. We had more powerful LED lights, for example, that lit up cave walls like a football field. And using modern software to analyze our camera images, we could identify the outlines of artwork that has faded so much over time that it is no longer visible to human eyes.

In 2015, I reached out to the speleological, or cave-exploring, groups in the region, and, through courses organized by the regional government, I taught them how to find cave art. I showed them different examples of rock art so that they could learn to recognize it and understand its value. In 2015, we had 70 graduates, and within a year, we added another 50 to our ranks. Speleologists are better prepared than archaeologists for doing deep surveys of caves, such as by climbing steep chimneys or descending into watery sinkholes with diving gear. The speleologists we worked with provided the legs to explore the caves, and we provided the eyes and expertise to see the art.

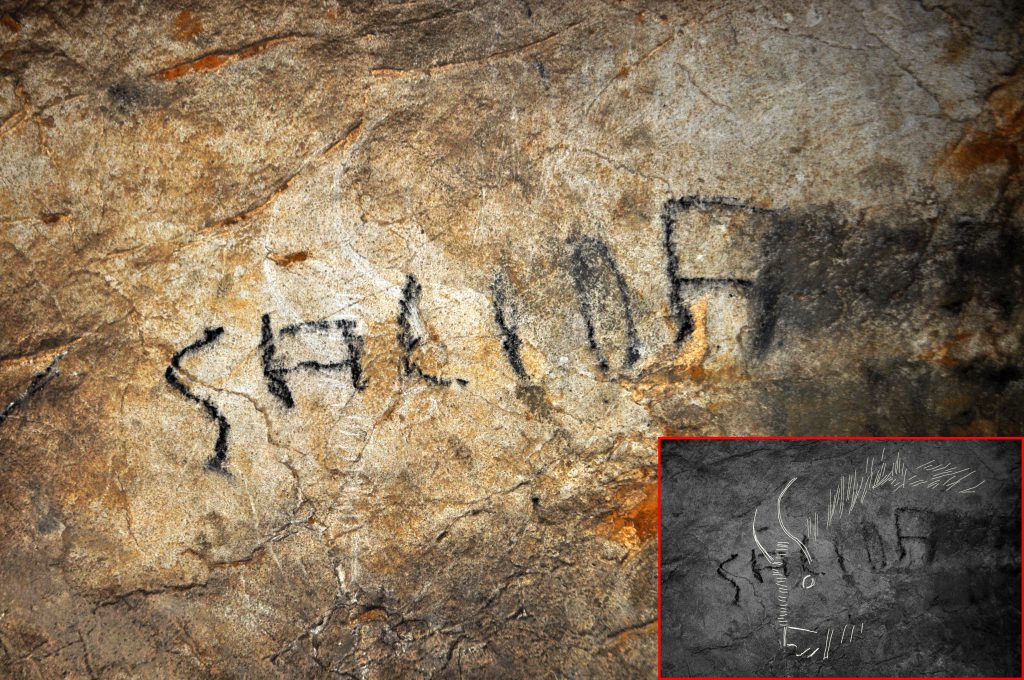

In the early stages of our search, we found rock art in well-known caves, hiding in plain sight where archaeologists and the general public had been before. Some of the artwork was so badly preserved that we relied on digital imagery to see it. For example, in Askondo cave, the outline of a horse had been painted over with modern graffiti by someone who presumably didn’t even notice the carvings underneath. In this cave, we also found paintings of red horses that had nearly disappeared over the 25,000 years that had passed since they were created.

In the ensuing years, this partnership between archaeologists and speleologists has yielded great results. The Atxurra cave system, for example, has been visited since at least 1882 (which we know because of graffiti that includes that year) and was first explored by archaeologists in the 1930s. But with the help of professional cavers, we were able to reach high chambers in the deepest areas of the cave, some 300 meters from the entrance. We discovered an 11-meter-long panel of art above a narrow platform that was 4 meters above the floor. By climbing to these precarious spots—as the artists must have done some 12,500 to 13,500 years ago—we have so far found more than 100 engravings and paintings of deer, horses, bison, and goats. We also came across some of the sharp flint stones that were used for engraving the artwork, and we identified the remains of hearths that were likely utilized for creating fires to illuminate the art.

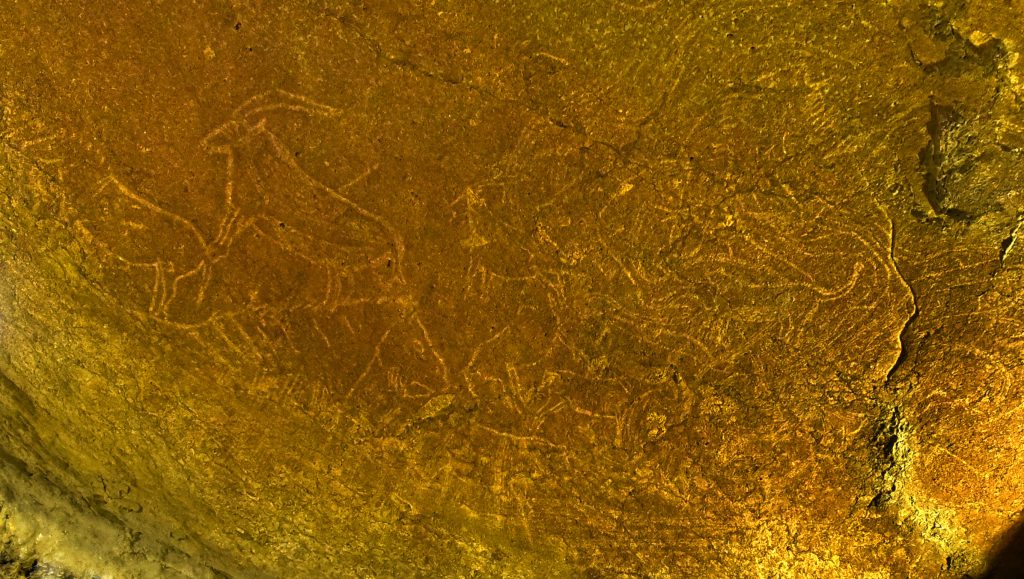

Another Basque Country cave the speleologists investigated was hidden below a residential building in the village of Lekeitio. The Armintxe cave’s entrance had been covered by rubble in the 1980s to prevent people from going inside, but there was a small entrance hole nearby in a communal garden. Cavers dug this out and climbed inside. The cave was dirty, muddy, and full of graffiti. But in an upper gallery, where the ancient floor had nearly eroded away, the speleologists found about 50 engraved animals that had been there for 13,600 to 14,600 years. What surprised us even more was that the panel showed two lions—an animal that had previously been seen in cave art in France but never in northern Spain.

We also had success in the well-known Aitzbitarte cave system, where our team had previously documented scarce cave art. Our team’s speleologists found several new, small chambers by clambering up a vertical conduit at the side of the principal gallery. Inside, they found two bison figures and other animals engraved and then lined in clay—a technique that previously had only been documented in France. This upper gallery was totally untouched, and the conservation of the artwork was superb. (Cave art is an extremely fragile heritage.) We could even see the fingerprints of the artist—or artists—in the soft clay on the wall.

By using new technologies and collaborating with speleologists, we have been able to fill in the map of Paleolithic cave art in Basque Country. The extensive and rich artistry displayed in these new findings offers fresh insights into the origin of symbolic expression and a window into regional artistic influences. The results have been amazing. We have tripled the number of decorated caves, which helps us better understand the first art pieces of the human race. While many researchers thought that all the major rock art sites had been discovered, we’ve proven them wrong time and time again.

The lesson is simple: We should never assume that everything has been done before. There is almost always more to be found. We just have to be willing to look.