Can Archaeology Help Restore the Oceans?

USING THE PAST FOR THE FUTURE

Off the southern California coast lies a little-known gem of the United States National Park system, Channel Islands National Park. Jutting from turquoise waters, the rocky islands harbor rich biological diversity and an archaeological record of the Chumash people and their Ancestors that extends back over 13,000 years.

For millennia, Chumash and other Indigenous communities nourished themselves by fishing rockfish from kelp forests, plucking abalone from tidal pools, and foraging the islands’ other maritime bounty. By the time Spanish explorers arrived some 500 years ago, large villages dotted island shorelines. A few thousand people dwelled in circular homes, which were dug into the ground and roofed with cattails, bulrush, and marine mammal skins.

Today Chumash descendants from the Channel Islands and adjacent mainland are thriving and undergoing a variety of revitalization efforts. This includes language reawakening and building and voyaging in tomols, or plank canoes. For decades, a handful of archaeologists have worked with these descendant communities to better understand their Ancestors’ lifeways and deep connections with the islands. This work has also revealed the history of local ecosystems—and how Chumash people sustainably drew from natural resources since the end of the last ice age.

As archaeologists long interested in the Channel Islands, we have recently shifted our attention from the past to the present and future. Our research findings and Chumash history have provided critical information for marine conservation efforts around this precious habitat.

More broadly, the work exemplifies why archaeology is a linchpin to environmental conservation: Archaeological research can uncover baselines—how ecosystems looked before humans inflicted walloping changes.

SETTING THE BASELINE

Ecological baselines provide a glimpse of past ecosystems: a sea brimming with life—from plankton to tuna; an African savanna running with gazelles and lions; North America’s grass prairies flush with bison and chirping critters.

Effective environmental conservation plans set ecological baselines at reference points prior to major human transformations such as commercial fishing, overhunting, illegal poaching, intensive agriculture, and industrialization. Without an appropriate baseline, natural scientists may arrive at false conclusions about what constitutes the “natural” world.

To reconstruct past ecosystems, archaeologists recover pollen and animal bones and teeth that indicate changes to flora and fauna. They measure the chemical composition of soils, minerals, and animal remains, which track ecological and climate conditions. And they employ genetic studies tracing the ranges, abundance, and diversity of plant and animal communities.

The research shows people do not always wreak havoc on environments. Around the globe, communities have tended landscapes and fostered biodiversity. This has been done through such practices as planting and controlled burning. Selective and sustainable foraging has benefited wildlife. For tens of thousands of years, people have imparted a range of effects on the natural world from enhancement to degradation. All of these human activities constitute important ecological baselines.

Knowing baselines is particularly important for marine ecosystems, which face such threats as overfishing, habitat alteration, and ocean warming. The challenge is that monitoring efforts (upon which many scientists base restoration efforts) began less than 100 years ago—after the advent of commercial and industrial fishing.

Archaeological perspectives, though, can illuminate oceans as they were hundreds to thousands of years ago—and how people have influenced those ecosystems.

CHANNEL ISLAND LIFE

In Channel Islands National Park, the far eastern edge of Santa Rosa Island holds the remains of the village of Qshiwqshiw, which translates to “bird droppings” in the Chumash language. With at least 119 residents and four chiefs, Qshiwqshiw was one of the largest villages on the northern Channel Islands in the 1400s and 1500s, immediately prior to Spanish arrival.

To the untrained eye, not much is left to see. Today remnants of the village’s epicenter sit on a low-lying coastal terrace flanked by white sandy beaches and a freshwater marsh. The landscape undulates under knee-high grasses, which obscure numerous large, circular depressions. Several meters in diameter, these shallow pits were the semi-subterranean dwellings of Qshiwqshiw residents. The houses (‘ap) would have included animal skin and plant-covered roofs secured with bent poles and branches.

In the early 2000s, our team of Chumash consultants and San Diego State University archaeologists conducted small excavations at Qshiwqshiw. We were interested in a period about 1,000 ago when at least 3,000 people inhabited the northern Channel Islands.

Across the islands, people fished primarily in watersheds adjacent to their villages to harvest what they needed for themselves and their families. Especially at a village the size of Qshiwqshiw, this may have stressed or depleted local resources. We wanted to know how Chumash Ancestors managed resources and whether their tactics were sustainable.

As expected, the islanders ate a lot of seafood: Among some 2,600 fish bones, we identified more than 30 types of fish, including mackerel, perch, and barracuda. With many mouths to feed, villagers also collected easy-to-gather and process intertidal shellfish such as California mussels, marine snails, and abalone.

Yet measurements of shells from Qshiwqshiw and other large Chumash villages demonstrate a reduction in mussel and abalone size over time. This forced fishers to pursue more swimming fish.

So, the question arose: Was the strategy unsustainable?

FISHING ACROSS NOT DOWN

Looking at the Qshiwqshiw menu more closely, we noticed choices that would have helped keep the marine ecosystem humming.

Today’s commercial and industrial fisheries tend to “fish down the food web.” This means they first target species near the top of the food chain or highest trophic level, such as swordfish and tunas. High trophic level species tend to have very important ecological roles, so their loss can be catastrophic. As those animals dwindle in numbers, the fishers move down trophic levels, targeting smaller and smaller, more short-lived creatures until the ecosystem crashes, and there is nothing left to catch.

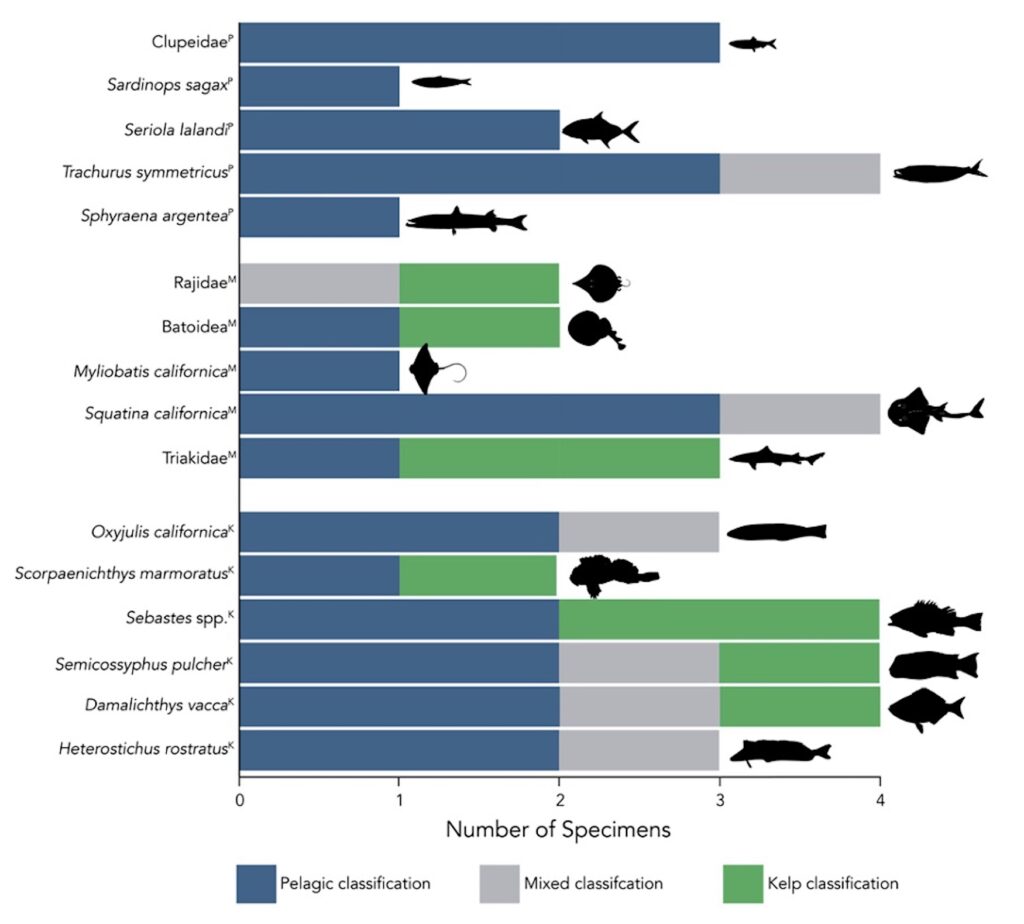

Qshiwqshiw fishers, in contrast, seemed to favor fish midway up the food chain of kelp forests. Nearly 60 percent of the fish bones we identified came from such species, including pile perch, rockfish, skates and rays, and houndsharks. Catching these fish required investment in technology (tackle, boats, line, and so on), time, patience, and local knowledge—and their fishing strategies likely minimized human impact on the ecosystem.

While focusing on mid-trophic fish, the Chumash community also caught seafood from across different habitats and levels of the food chain—from sardines to sharks. We say the residents were “fishing across, rather than down, coastal food webs.”

STABLE FOOD WEBS

To gauge whether Qshiwqshiw strategies sustained the ecosystem, we performed chemical analyses on several dozen recovered fish bones. The method revealed information about the food web’s foundation: photosynthetic organisms that capture the sun’s energy and convert it into edible sugars.

Among the key marine photosynthesizers, kelp that grows on nearshore ocean floors and phytoplankton that floats in open water carry distinct chemical signatures in their amino acids. These signals get passed up the food chain to creatures who gobble kelp or phytoplankton, to fish who eat those creatures, and so on to tuna, swordfish, and apex predators.

Measuring these signals for the Qshiwqshiw bones, we found kelp-like values, phytoplankton-like values, and some fish that showed a mix of both sources. It seems these fish, caught by Chumash Ancestors, had been feeding in kelp forests and the open sea. A millennia ago around the northern Channel Islands, offshore and nearshore habitats exchanged nutrients and the energy captured by photosynthesizers at the bottom of their food webs.

Ecologists call this “energetic coupling”: It is a marker of stable food webs.

Think about it in terms of a stock market portfolio. If you invest all your money in a single company, for example Offshore Creatures Corporation, and that company fails or its stock price tanks, you stand to lose your nest egg. Alternatively, you could diversify your portfolio and invest in multiple companies: Offshore Creatures Corporation, Kelps-R-Us, and Sandy Beaches LLC. Then if one fails, your investments in the other stocks will keep you afloat.

The same concept translates to food webs. Plant and animal communities supported by different energy sources from multiple habitats tend to be healthy and resilient. They can overcome short-term disturbances from natural climatic change or human harvest. Our research suggests that prior to Spanish arrival, the northern Channel Islands marine ecosystem was well-balanced and resilient, with nearshore, kelp forest, and offshore habitats all supporting one another.

This connectivity helped sustain Chumash fisheries and healthy marine ecosystems for millennia. Even as Chumash fishers intensified their harvest of local resources, these short-term impacts were balanced by nutrients and energy from nearby habitats. Chumash knowledge of these systems, obtained over millennia, provided the framework for targeting different habitats and organisms, and promoting sustainability.

BASELINES ARE JUST THE BEGINNING

Commercial and industrial fishing strategies are fundamentally, even catastrophically, different. These fisheries usually harvest a single species or from a single habitat, an unsustainable venture that can collapse fish stocks. Once overexploited, the fishers target new species, and the cycle begins again.

This pattern severs the energetic links that once made habitats more resilient to human harvesting and natural climatic change. If humanity continues with business as usual, our ocean ecosystems will continue to degrade. Marine habitats will be unable to adapt to the pressures of climate change and world hunger.

Archaeology and deep history offer no panacea to the environmental challenges human beings have created and now face. But the past does provide baselines and time-tested ways to live sustainably, which should serve as models for the present and future.