With the Fall of a Tree, Archaeology Returns to Liberia

In 2019, in the aftermath of a particularly severe storm, a massive cotton tree came tumbling down on Providence Island, Liberia’s premier heritage site. The nation mourned its loss.

Among many African-descended peoples, cotton trees (Ceiba pentandra) are considered the abode of good and evil spirits. But even aside from spiritualism, this fallen tree held a special place in Liberian hearts.

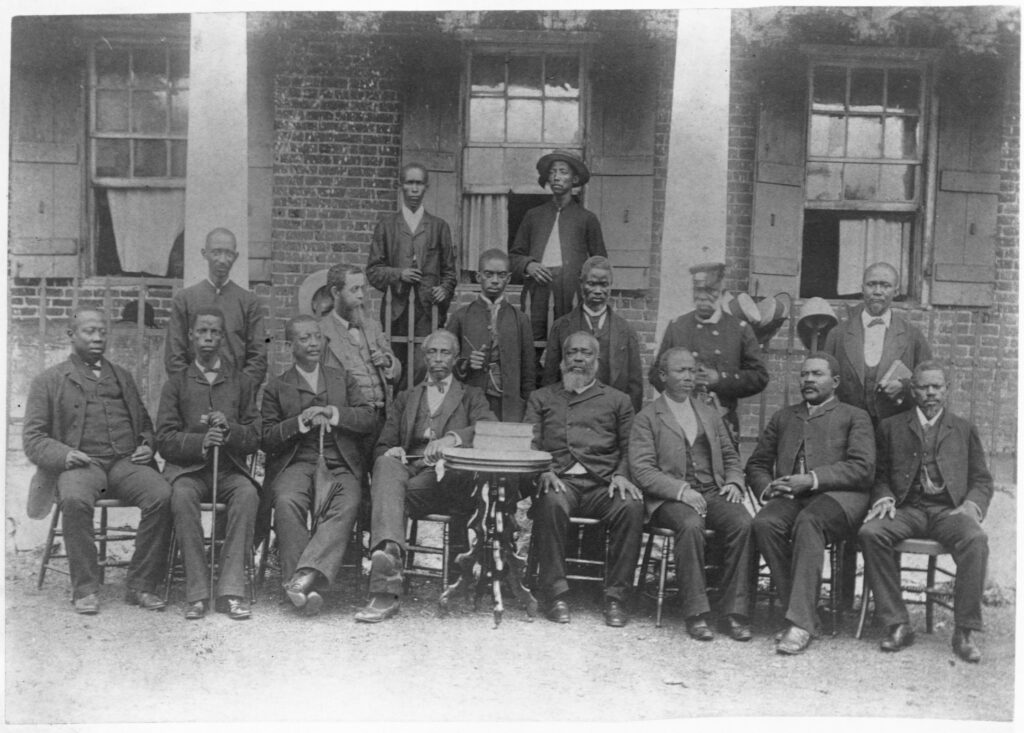

It was said to be the site of the original meeting between Indigenous Liberians and the Black Americans who arrived on this shore in search of freedom in 1822, nearly 200 years before the tree fell. The tree, therefore, is a symbol of Liberian history. It represents the unity and conflict that has underscored the relationship between Indigenous peoples and Black American settlers, or Americo-Liberians.

While many lamented the tree’s fall on a symbolic level, its literal collapse unearthed a treasure trove of archaeological heritage. The root matting below revealed thousands of objects dating to the periods before, during, and after the momentous 1822 arrival of Black American settlers.

The Back-to-Africa Heritage and Archaeology (BAHA) project—founded by Caree Banton, Matthew C. Reilly, and Craig Stevens in 2018—conducted salvage excavations after the cotton tree came crashing down. [1] [1] Funding for the BAHA research featured in this story was provided by the National Geographic Society. This marked the return of archaeology to Liberia after a roughly 50-year hiatus largely caused by a devastating Civil War.

The objects found beneath the tree, along with others recently uncovered across the landscape, speak to the global reach of Liberian trade in the years immediately following the 1822 settlement. But this is only part of a much deeper and more complex story that’s coming to light with the BAHA team’s exciting finds.

Now the question remains: How will this new chapter in Liberian archaeology inform the complex historical divide between settlers and Indigenous peoples?

REWRITING NARRATIVES ABOUT LIBERIA’S PAST

By all accounts, the first archaeological excavation in Liberia occurred on January 1, 1961. That New Year’s Day, Liberia’s community development adviser, Kenneth Orr, who arrived in the country the previous year, veered from his official duty and collected potsherds from an abandoned town near Gbarnga, presently the provincial capital of Bong County. Other professionals, mostly from the U.S., conducted excavations throughout the 1960s and into the ’70s.

Then, a bloody coup in 1980 ended 133 years of Americo-Liberian hegemony over the majority Indigenous population. This was followed by a horrific 14-year Civil War.

Today, as Liberia continues to rebuild, the return of archaeology takes place at a crucial moment. In 2021, the Liberian government announced the 2022 celebration of the 200th anniversary of the arrival of free Black Americans who later founded Liberia in 1847. Many people were understandably caught off guard by the celebratory announcement. In the minds of Liberians, the coup and Civil War are dark memories that cast long shadows.

Still, the bicentennial marked a critical time for Liberians to reflect on their identity and their historic and contemporary relationship with the United States. That much was made clear when bicentennial festivities on Providence Island featured a large wooden replica of the Mayflower, juxtaposing the island with Plymouth Rock in the U.S.

During this time of reflection, archaeology is offering a way to rethink one-sided perspectives on Liberia’s past. The new finds are also partly filling gaps in the country’s story and challenging some hard-to-shake misconceptions.

According to the commonly accepted narrative of Liberia’s founding, in 1821, White American colonization agent and Navy Lt. Robert Stockton held a gun to the head of Indigenous leader King Peter. This threat forced a land treaty reminiscent of the establishment of U.S. territories centuries earlier.

But a recent archival discovery by Liberian scholar C. Patrick Burrowes might present a different narrative. The recovered document, as interpreted by Burrowes, revises earlier ideas about Stockton’s gunplay and White colonial intimidation. Instead, it suggests consenting African leaders in the area signed a fair agreement.

Yet Burrowes cautions that by relying on written records, one risks telling a one-sided story from the point of view of the U.S. government and the American Colonization Society, an organization founded in 1816 by leading Americans with the intent of relocating African Americans to Africa. And in any case, the land agreement was signed by a Navy officer (Stockton) while an armed U.S. vessel hovered nearby.

In 1820, the first West African–bound freed Black emigrants sailed from the U.S. on Liberia’s version of the Mayflower, the Elizabeth. The emigrants endured a lengthy limbo in Sierra Leone, where many died and others struggled with disease. In 1822, emigrants from the U.S. established themselves in what became Liberia.

The majority of 19th-century migrants to Liberia came from the mid-Atlantic states and the Deep South. Virginia led all states, with at least 3,741 emigrants, and Georgia was second, with at least 2,164. Place names across Liberia reflect this history, with townships and counties such as Louisiana, Virginia, White Plains, New Georgia, Maryland, and Greenville dotting the coastal region. State-by-state divisions also surfaced in disputes among migrants.

As an American colony resulting from efforts to expel Black Americans, Liberia signaled the limits of freedom for African Americans and the possibilities of a multiracial democracy in the U.S. Many migrants from the South were born free, but about one-third were emancipated on the condition that they go to Liberia. Some states even passed laws stating that freed African Americans would have to leave the state within six months. This prompted many people to journey to Liberia to preserve their freedom—sometimes against their will.

While some were excited by the potential opportunities afforded by emigration to an African homeland, others expressed anguish over leaving behind family, friends, and the lives they had built under circumstances of racial violence.

SETTLER-CENTRIC ARCHAEOLOGY IN LIBERIA

Deeper research into Liberia’s past has been hindered by the fact that, until recently, few archaeological projects had been conducted in the country. The research that did take place prioritized ancient history, including developing chronologies of the region’s first inhabitants, tracking stone technologies, and documenting trade. Liberian ancient history was mainly studied by foreign (White) experts who followed a colonial model of archaeology.

As a result, objects largely ended up in museums and universities in the U.S. In addition, archaeological studies rarely investigated the critical Atlantic era of Liberia’s past, including the controversial years surrounding the 1822 settlement.

Scholars of Liberian colonization often explored experiences of various groups from different U.S. states and the Caribbean. Other researchers have examined the ways questions of representation, governance, and citizenship affected colonies of empires. This settler-centric perspective sustains the idea that African and other Indigenous histories only become visible with European colonial encounters.

In historical writings about Liberia, there is a conspicuous Indigenous presence but no real sustained and substantive accounts. In this literature, Indigenous peoples form an afterthought and often a footnote, occupying a peripheral space within the essays rather than their core.

This bias is all the more surprising when considering that Liberia’s Indigenous peoples have always constituted the overwhelming majority of the nation’s population, now more than 5 million people. With the arrival of 19th-century settlers, Liberia became home to 17 ethnolinguistic groups, belonging to three subgroups of the larger Niger-Congo language family of Africa.

Thankfully, today archaeology in Liberia is more diverse, both in terms of the researchers and the scope of their investigations. And the evidence they are unearthing is creating more inclusive narratives about Liberia’s past.

AFRICAN-LED ARCHAEOLOGY IN LIBERIA

BAHA represents a collaboration between foreign, largely African-descendant scholars; Liberian institutions and professionals; and Liberian students. Their work on Providence Island foregrounds the intersection of Liberia’s deeper past with more recent centuries of colonial contact and settlement, right up to the post-conflict present.

Since 2019, most of the thousands of objects the group recovered from Providence Island—including those under the cotton tree—were not made in Liberia. In fact, much of the material culture reflects broader trading patterns across the Atlantic world. For instance, large quantities of German-made stoneware jugs testify to the young nation’s early and extensive economic relationship with Germany. (This connection ruptured in 1917 when Liberia joined the U.S. and other Allied forces during World War I.)

Other materials might indicate extensive trade among Indigenous groups—both between Indigenous groups like the Vai and with passing European traders—prior to Americo-Liberian settlement. For example, researchers found English-made creamware vessels that were produced in the latter decades of the 1700s. These finds suggest that either Providence Island had long functioned as a trading hub during the Atlantic era prior to 1822, or arriving settlers brought older, less expensive wares with them on their transatlantic journeys.

Finding such archaeological objects was not necessarily a surprise given what is known about the years of settlement. But the cotton tree had more stories to tell.

Intermixed with everyday items made in far-off places such as Europe and the U.S. were unmistakable signs of Liberian innovation and cultural resiliency. Liberian team members recently trained in archaeological methods unearthed ceramics made by Indigenous peoples long before the arrival of European traders and Black American settlers.

Currently, only rudimentary ceramic “typologies”—categories for types of ceramics that indicate their period and place of origin—exist for Liberia. This means we cannot yet conclusively say who produced, used, or discarded these vessels. But preliminary analysis has revealed a diversity of clay sources, vessel shape, and decoration. This indicates ceramic vessels were likely being traded across what would become Liberia.

Excavated materials are now safely in the care of the National Museum of Liberia, where staff members partnering with BAHA are eager to design exhibitions for some of the first provenanced archaeological collections they’ve held since the institution was looted during the Civil War. These items are helping to write new, deeper chapters in the history of Providence Island.

These chapters are in need of careful editing and revision. But they have the potential to highlight how Indigenous Liberians used the island in the centuries prior to 1822 and the complex relationships that emerged as the nation of Liberia took shape.

THE FUTURE OF ARCHAEOLOGY in LIBERIA

On January 7, 2022, 200 years after the arrival of the first settlers, the Liberian government and Indigenous elders reportedly planted two baby cotton trees on Providence Island as part of the bicentennial commemoration. Both seedlings, in the recollection of the Indigenous elders, represented the male and female trees that towered over Providence Island for about two centuries.

Soils on Providence Island now have an important role to play in the growth of the new trees. Similarly, the material heritage found within these soils can play a role in creating more inclusive narratives of the Liberian past as Liberians at home and abroad optimistically look to a brighter future.

The first generation of Liberian archaeologists and heritage professionals will decide how to help build a sustainable material heritage industry in Liberia. And that future, too, looks bright.

In the summer of 2022, recent graduates of the University of Liberia, with the BAHA team, unearthed locally made ceramic sherds at the base of the cotton tree. As they excavated the objects, they weren’t thinking about the mythical founding stories of Liberia. Instead, they expressed excitement that Providence Island, which remains a venerated space of diaspora and nationalist heritage, had a tangible material past they could call their own.