What Ancient Gender Fluidity Taught Me About Modern Patriarchy

In my hands, I’m holding a 2,500-year-old clay figure of a person, carved by someone long ago in what is now my home country of Ecuador. The figure has the busty chest of a woman but wears the clothes of a man. It is neither one nor the other. It speaks of an era in which gender was perhaps not a binary characteristic but something more fluid and open to possibilities.

For more than 15 years, since the start of my doctoral research, I have been studying the iconography of coastal Ecuador. After looking closely at more than 3,000 figures carved in clay that were made over millennia, I have started to see some intriguing patterns.

Throughout this collection, I see figures that combine elements they often associated with male and female genders: combinations that other archaeologists seem to have overlooked or dismissed. And I see a stark transition about 2,500 years ago, from what seems to be an art focusing on female symbolism to an art perhaps trying to legitimize a patriarchal structure. The figures’ shifting poses, facial expressions, and clothing have something to say about changing attitudes regarding gender politics and positions of power.

In decoding these gender relations of the past, I have begun to think differently about the present—and my role in a modern, chauvinistic, Ecuadorian society. These figures, though carved thousands of years ago, have spoken to me about my own life and relationships. They have made me see things in a new light.

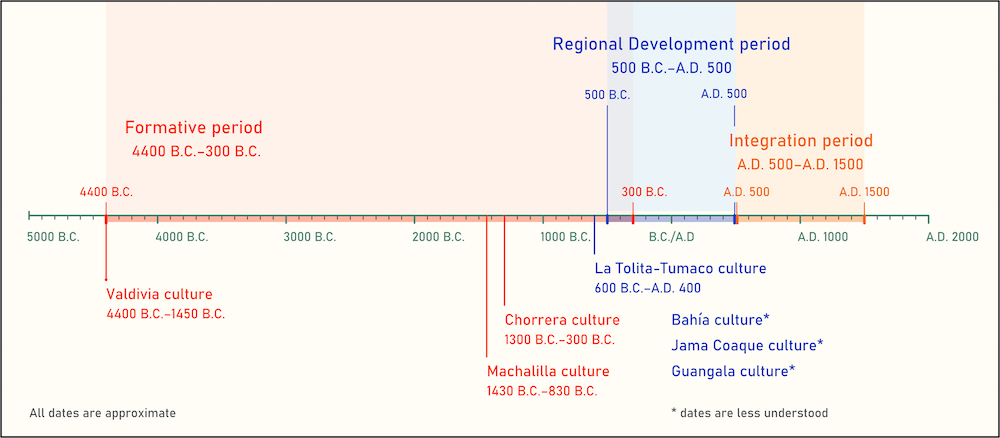

The coast of what is today Ecuador hosts the lengthiest history of human figurine production in the Americas. This tradition endured uninterrupted for at least 5,000 years. Archaeologists call the three periods within this time span the Formative period (4400 B.C.–300 B.C.), the Regional Development period (500 B.C.–A.D. 500), and the Integration period (A.D. 500–A.D. 1500). (These dates are very approximate; see timeline.)

The earliest figurines date back to 3500 B.C., in what scholars call the Valdivia culture. The hierarchical, agricultural societies of the Regional Development period then produced thousands of clay figurines, depicting people, animals, and mythical beings, as well as very delicate gold and platinum ornaments. The creation of figurines ended around A.D. 1500, with the arrival of Spanish conquistadors.

Although the function of all these figurines is not clear, at some point they were made using molds, presumably to produce them in great numbers. I believe they were made to communicate ideas, to send messages to a broad audience.

When I started looking at the corpus of figurines from the La Tolita-Tumaco culture (~ 600 B.C.–A.D. 400), it was not hard to see their first layer of meaning: I saw human beings, animals, or natural objects in the figures before me. It also appeared easy, at least initially, to distinguish individuals who would have been women and men. Initially, I assumed this binary choice was the only possibility.

However, problems rapidly arose in my categorization.

I could see, as others had previously noted, an association between features such as breasts and dress such as skirts, or a lack of breasts with loincloths. But the ancient artisans did not always express this division, sometimes combining female physical features with male dress, and vice versa. This did not happen often, but there are enough such figurines to build a category of what now might be described as nonbinary or transgender people.

Read more from the archives: “Stop Erasing Transgender Stories From History.”

After finishing my doctoral research, I started looking at other iconographic styles from the region. I found similar mixed-gender figurines in the Bahía, Jama Coaque, and Guangala styles—all from the Regional Development period—but also in the earlier Valdivia style of the Formative period.

Although archaeologists have examined these figurines for nearly a century, no one else seems to have pointed out that this blending of gender characteristics might have been intentional. Researchers do not mention it or, if they do, the issue is solved with a technical explanation. One scholar, for example, assumed it might have been because the artisans were reusing female molds, for economy, and dressing them up as men. This doesn’t seem plausible to me; both kinds of figurative molds were available, after all.

Maybe other researchers didn’t notice this pattern because of their own gender biases. The modern patriarchy tends to naturalize concepts like binary gender relations as if they were timeless and unchangeable. They are not.

Roughly 2,500 years ago, with the beginning of the Regional Development period, there was a remarkable shift in the figurines.

During the earlier Formative period, and particularly in the earliest Valdivia phase (but also in the following Machalilla and Chorrera phases), the great majority of the human figures emphasized biologically female attributes. The breasts are large and frequently the pubic hair in the pelvic area is highlighted. There is little sign of individuality: All the figures are standing, are not dressed or adorned with jewelry, and have uniform facial features. The figurines do not appear to be depicting individuals but rather some concept of shared feminine symbolism.

In contrast, in the subsequent Regional Development period, with cultures like La Tolita-Tumaco, Bahía, and Jama Coaque, the collection of figurines expanded to include hybrids of animals and people—and men. The male figurines come in all sizes and are often loaded with empowering paraphernalia. They show men in action, with elaborate dress and adornments; men with erect penises who carry weapons or musical instruments; men dancing, driving canoes, hunting, or fighting; men filling the public sphere of life.

Meanwhile, the female depictions from this period usually imply motionlessness. Frequently, they hold children of different ages, especially breastfeeding infants. Mostly, the women are wearing only a skirt and have perhaps a few, basic ornaments.

Very little is known about gender roles in these ancient societies, and these depictions do not necessarily mirror people’s lived reality. What I see instead is an intention to transmit an ideal of what was considered natural in male and female actors. I see a goal of convincing people that an asymmetrical gender system—a patriarchy—is normal.

Archaeology itself has long been chauvinistic and patriarchal, conducted largely by men interested in what men were doing. In the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, scholars such as Sally Slocum, Margaret Conkey, Joan Gero, and Janet Spector brought to light how women have not been taken into account in traditional anthropological interpretations: For example, many studies emphasized activities associated with men (like hunting) and undervalued activities associated with women (like gathering). Later, other scholars added that children and individuals who are not gender binary have suffered the same fate of exclusion.

Yet the archaeology of gender is still viewed today as something of a fad.

Approaching archaeology with an emphasis on gender has been the greatest challenge of my career thus far. This approach bridges the distance between the object of study (items from the past) and me, and in turn, makes me into an object of study. Looking at these ancient figurines and trying to interpret the sex, gender, and power relations they reflect has led me to question myself and my surrounding environment in the same manner.

There are many stereotypes about gender roles that are accepted in contemporary society as natural and that limit the possibilities of women to act in public spheres with self-confidence. As U.S. tennis star Serena Williams recently said in a July 2019 interview with Harper’s Bazaar, “Why is it that when women get passionate, they’re labeled emotional, crazy, and irrational, but when men do, they’re seen as passionate and strong?”

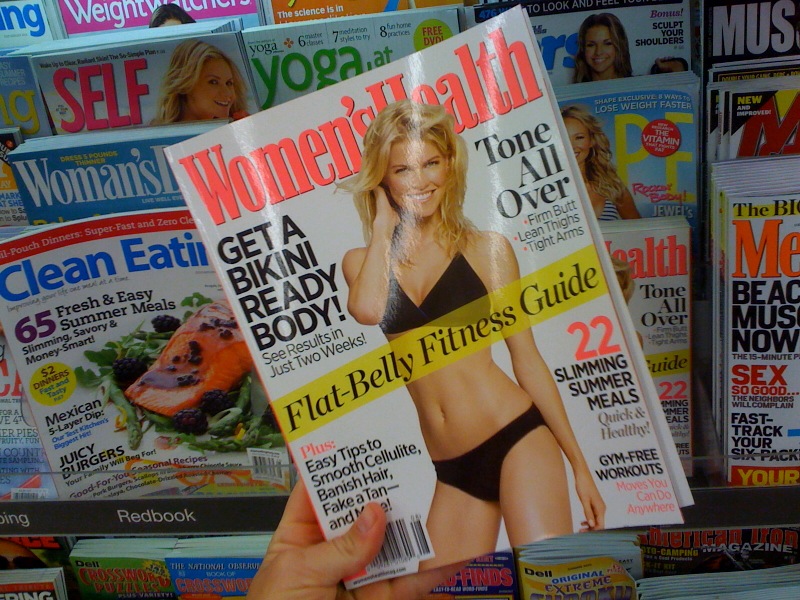

Today the magazines at my local grocery store in Quito feature women depicted in an idealized manner. These women are well-dressed and styled, happily juggling careers, homes, husbands, and children. On the cover of Hogar magazine, a former beauty queen shows off her smiling baby girl. In reality, I have never seen a woman dressed and put together in this manner while caring for her child.

While art does not always perfectly reflect life, it does shine a light on the values and attitudes of a culture. Today’s magazine covers throw a spotlight on our modern gender politics. The figurines of the past, I suspect, do the same.

I am someone who, more or less, matches the “standard” of a woman in Western society: cisgender, heterosexual, mother. I fit the mold. Yet my life is not perfectly easy.

When I started writing this essay, I did my work while a paid babysitter cared for my little girl. I enjoyed a generous grant awarded by a German foundation that allowed me to conduct research in one of the best libraries in Europe. In order to be able to do that for four hours each day, I paid exactly half of my grant to babysitters. Yet the expectation was that my academic production would be the same as a man who is a father and received the same grant, and who very rarely is charged with the full-time responsibility of caring for his children.

Hidden asymmetries in gender relations are rife in academic politics. The chairs of academic departments are mostly occupied by men. I was the first woman to hold the chair of the anthropology department in the university where I work, and it was a hard experience. I found that people questioned my decisions and instructions in ways they did not with men.

I wonder how life was in ancient Ecuador. Were there people with gender identities other than male and female, and how did they fit in? Did the women depicted in the figurines accept a patriarchy imposed from 2,500 years ago onward? Or were there some “rebel female potters,” as I suggest in a paper published in 2019? I have seen some figurines that could be depicting lesbian couples and others where female figures adopt the powerful poses usually reserved for men.

I am aware that my critique holds a trap for myself. I blame modern patriarchy for causing archaeologists to see things in a certain way, but what about my own perspective? Is it not influencing my interpretation too? Sure, that’s partly the case. But I think it is always useful to take up the unusual viewpoint for a while, even if it has its own biases. At least those biases are different and so open us up to new vistas and novel possibilities about past and present societies.

Understanding the origins and history of gender relations is an important step in understanding the present. To dismantle patriarchy, it must first be unmasked.