Archaeologists Should Be Activists Too

When Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, paused counting votes for one night during the 2020 presidential election, unfounded conspiracy theories about election security began to fly.

Community groups mobilized to pressure the election board to adopt an effective plan to count every vote accurately and without interruption. As a member of one of those groups—Lehigh Valley Stands Up—I (Allison) was committed to helping. Within a few hours, we had collaborated to choose a location for a strategic action: a bridge between counties. We had crafted our messaging, and our protest was covered by The New York Times.

The action was impactful, and our demands were met. The event’s success came out of the complementary expertise of activists in the Lehigh Valley—including mine as an archaeologist.

Archaeology and activism may not seem like natural partners. Many people think of archaeologists as concerned only with long-gone communities, digging up and untangling stories of the deep past. But archaeology, and its umbrella discipline of anthropology, are, in fact, well-suited to activism—and not just because the logistical skills developed through fieldwork come in handy when organizing protests. As disciplines, anthropology and archaeology are entirely about people and about making sure that everyone’s stories are understood and heard—including, and especially, those of the most marginalized groups.

These disciplines can be about justice at their core—but only if we make them so.

The past three decades fortunately have seen certain corners of archaeology focus much more on underserved voices of the past—particularly in historical archaeology, community archaeology, Indigenous archaeology, and feminist archaeology. This represents an intellectual commitment to understanding the material dimensions of past class, racial, and gender oppression not fully captured by today’s history books—to challenge systems of power in the past and in the present.

This is an important step forward. Archaeologists can and should make sure that their research, writings, and teachings within academia are helping to advance the causes of social justice. But we also argue that to accomplish this aim, archaeologists need to go much further than reorienting their academic research: Archaeologists must enter into coalitional work with community organizations and activist groups if we are to effect radical transformational change in the world.

Justice work, at its best, is driven by a sense of urgency—doing work that matters, now, to real people. This is because justice work is motivated by connections to people and to places experiencing harm in the present. Good justice work is care work, committed to compassion, capacity-building, and supporting the well-being of community members, activists, and scholars alike.

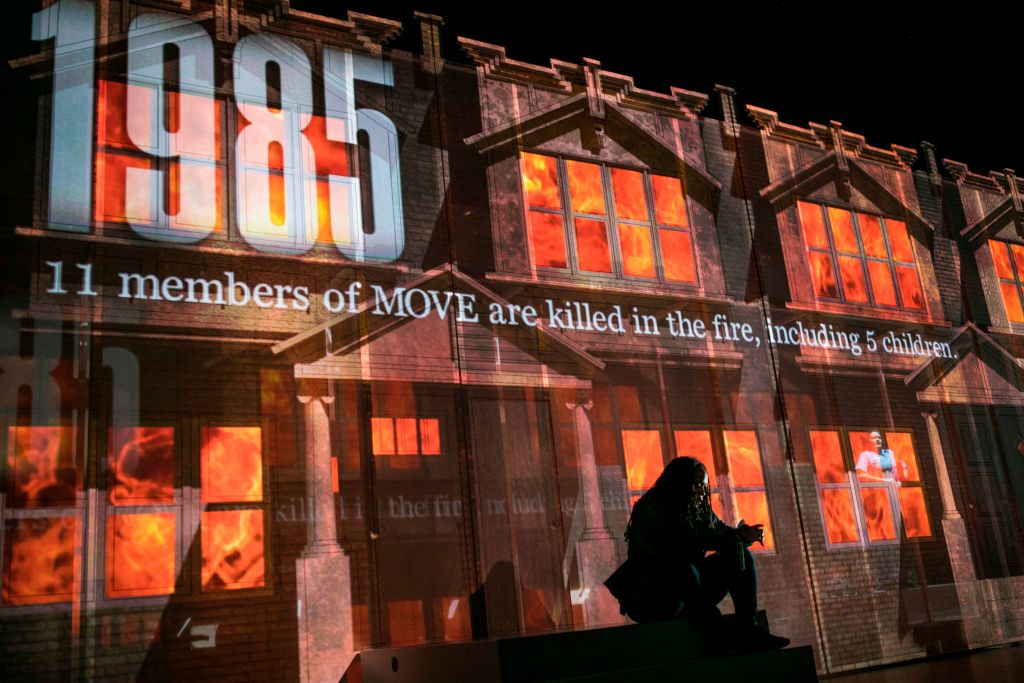

Archaeology could certainly use more of all of these—urgency, harm reduction, and care. Take, for example, the scholarly response to the ongoing case of the unethical holding and treatment of remains of African Americans at the Penn Museum—including it retaining the remains of two children who died when city police bombed a Black revolutionary organization called MOVE on May 13, 1985.

After local journalist and organizer Abdul-Aliy Muhammad broke the story that the remains of a young MOVE bombing victim had been used in a 2019 Princeton course video, it became clear that the remains of children, thought to be Tree and Delisha Africa, had sat in a cardboard box for decades, while the family thought their murdered loved ones had been buried in 1985–1986.

Several Penn anthropology faculty and students—notably, those with already existing connections to the struggle for racial justice around Penn’s collections of human remains—have joined with Muhammad and the MOVE organization to clarify the chain of custody and to support the Africa family’s demands for repatriation and reparations. This includes Krystal Strong’s tireless advocacy, Deborah A. Thomas’ work of bearing witness, and Paul Wolff Mitchell’s open-access archival report.

These are steps in the right direction to redress the violence and harm done across generations to Black and non-White communities, as called for in a joint statement of the Association of Black Anthropologists, the Society of Black Archaeologists, and the Black in Bioanthropology Collective in response to this recent scandal.

Clearly, living up to archaeology’s transformative potential requires careful, compassionate, and intentional relationship-building between activists and scholars.

One way that archaeologists have contributed to movements is to uncover the stories of marginalized people who didn’t, or couldn’t, write about their own experiences. This work, at its best, demonstrates not only the injustice faced but also the agency exercised by past people. It makes sure that no groups are forgotten, dismissed, or misunderstood.

Two projects from the University of Denver stand out as exemplary. The Amache Research Project, for instance, works to uncover lived experiences of people incarcerated in a Japanese American prison camp from 1942–1945. The Colorado Coalfield War Archaeological Project has documented the violence brought upon striking workers by private corporations and the state in southern Colorado between 1913 and 1914.

Coalitions create a complementary circle of advantages for both activists and archaeologists.

Much discussion in archaeology has focused on combating pop science takes on Paleolithic “Venus” figurines, small anthropomorphic carvings and sculptures that frequently have very large bosoms and buttocks. In popular media, these figurines are almost always identified as highly sexualized women made by men to satisfy their sexual fantasies. But archaeologists and physical anthropologists such as April Nowell and Melanie Chang have pointed out that these assumptions obstruct the objects’ scientific study. There are other possible interpretations, they note: The figurines may represent gender identities other than male and female, may have been produced for the sexual stimulation of others besides men, or may not have even been perceived as erotic at all in their original context.

But archaeology’s influence is not just limited to what academics study; it also involves what archaeologists do. University of British Columbia anthropologist Bruce Granville Miller, for example, has testified in court on cases of land rights and tribal recognition. Along with Gustavo Menezes, he has offered guidance to other anthropologists on how to act as expert witnesses against the disenfranchisement of Indigenous communities.

For some of us, our roles as teachers and administrators offer opportunities to design and implement inclusive policies in education and university life. All of these are ways in which archaeologists can and should effect tangible change through action, in order to bring about a more just world.

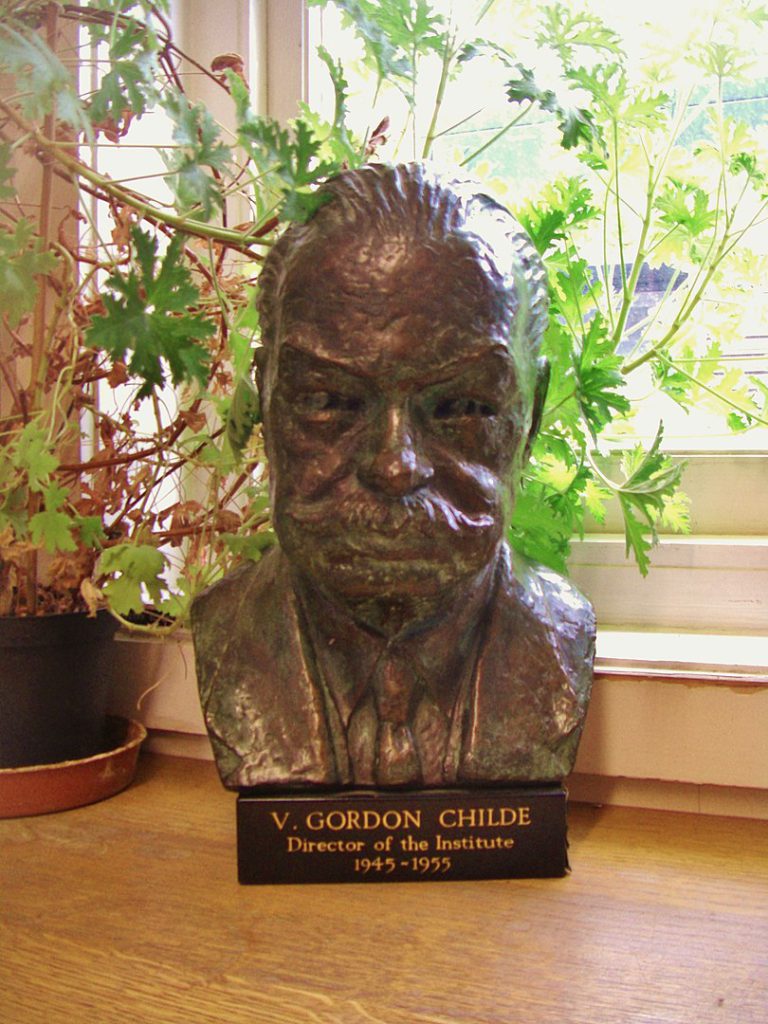

There is a long precedent for archaeologists involving themselves in political work. In the 1930s, Australian archaeologist Vere Gordon Childe wrote and lectured about the political misuses of the past, particularly in his efforts to debunk the fraudulent use of archaeological and anthropometric evidence by eugenicists and Nazi propagandists. Childe consciously chose to write for popular audiences and—if more than a dozen bestselling books are any indication—he was wildly successful. But Childe was also well aware of the limits of anyone’s ability to change the world through research, writing, and teaching. So, Childe went further.

While holding the Abercromby professorship of archaeology at the University of Edinburgh, Childe chaired the local chapter of the Association of Scientific Workers (AScW), a union of academics and industry technicians that agitated for peace, progressive education, and socialism. AScW called on scientists to acknowledge that their research was an unavoidably social practice, meaning that research and results were not and could not be entirely objective but rather were embedded in and infused with politics.

More than this, AScW argued that scientists must play a part in social and political struggles, for example, by fighting for better working conditions in the laboratory and the lecture hall. The AScW also believed it was scientists’ responsibility to educate people about how to protect themselves from bombs in wartime, how to eat well, and perhaps most importantly of all, how to think rationally and critically.

Childe’s involvement with the AScW and their scientist-citizen coalitions was not separate from or incidental to his background as an archaeologist. As archaeologists continue to discuss how we can contribute to grassroots and collective action for social justice, we would do well to follow his lead.

An important modern example of coalitional work is the Mapping Historical Trauma in Tulsa From 1921–2021 project directed by University of Tulsa’s Alicia Odewale and Brown University’s Parker VanValkenburgh. One of the worst episodes of racial violence in 20th-century America, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre decimated the once-thriving Black community of Greenwood, its inhabitants murdered or displaced by a White mob. And yet, the massacre was largely erased from historical memory.

As part of centennial efforts, Odewale and VanValkenburgh approached the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre Centennial Commission—a group of descendants, educators, activists, and cultural leaders either from or working in the Greenwood district of Tulsa—with an idea for an archaeological project and a provisional budget. From dialogues with community stakeholders, a four-year, community-focused project emerged that is not only accountable to but in fact led and funded by its stakeholders. As a result, this project is designed to pursue restorative justice, heal historical trauma, and uplift histories of resilience.

Coalitions like these create a complementary circle of advantages for both activists and archaeologists. Archaeologists have pragmatic skills to offer, from laying out timelines, to recruiting participants, to administering first aid in the field, to operating on shoestring budgets.

At the same time, the greater our exposure to different forms of collective action, the better our fieldwork will be. Researchers are compelled to ask new questions and find new approaches as we engage with those to whom our work matters.

There are still some who argue that scientists maintain their authority only when they remain objective, separate from current political concerns. Many academics have decried this view for decades, demonstrating that fully objective science has always been more of a myth than a reality. Science has always been shaped by the contemporary concerns of the time and place in which research occurs.

Scientific inquiry can be authoritative because of its responsibility and relevance to pressing issues for real people, not despite it. This idea is gaining more widespread acceptance. And it is particularly true for archaeology, where the places we are able to dig and the questions we ask about the past are so intertwined with issues of politics and injustice.

The only way to effectively push for the changes that the archaeological community wants to see is to exercise our capacity for collective action. In shaping a discipline that privileges compassion, archaeologists should be listening to, learning from, and working alongside the communities most affected by injustice.