Preserving the Voices of the Antioch Colony

The chronicles of ordinary Black Americans who lived and labored in Texas in the late 19th and early 20th centuries are largely unheralded. That’s especially the case for narratives on what transpired for the 250,000 Blacks in Texas who were emancipated on June 19, 1865—more than two years after then-President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

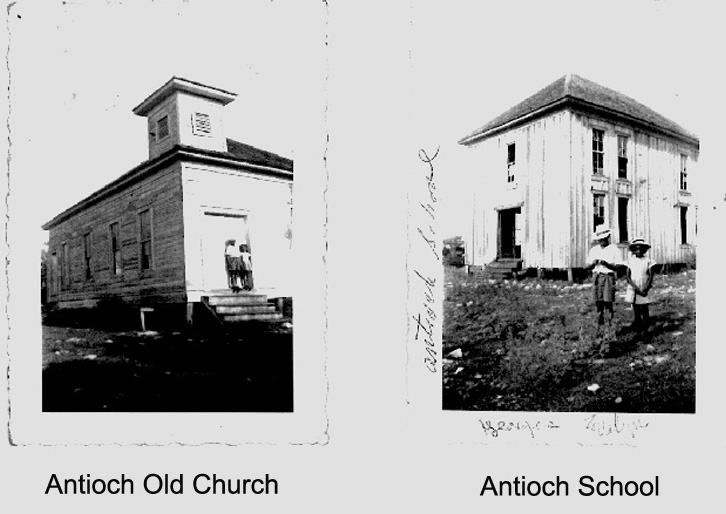

When freedom came, most possessed little more than the clothes on their backs. Yet, across the state, thousands of freedmen audaciously registered to vote and Black families formed communities and built churches and schools.

What did they envision for themselves and their heirs? What challenges did they face? What became of their descendants? And what legacy have these individuals left us with?

As a historical archaeologist, these are the questions that guide my research at the Antioch Colony, an all-Black settlement in Hays County that was founded on the heels of emancipation. Figuring out how Antioch’s settlers and their descendants maintained a thriving community from the late 1860s to the 1940s is like working on a jigsaw puzzle.

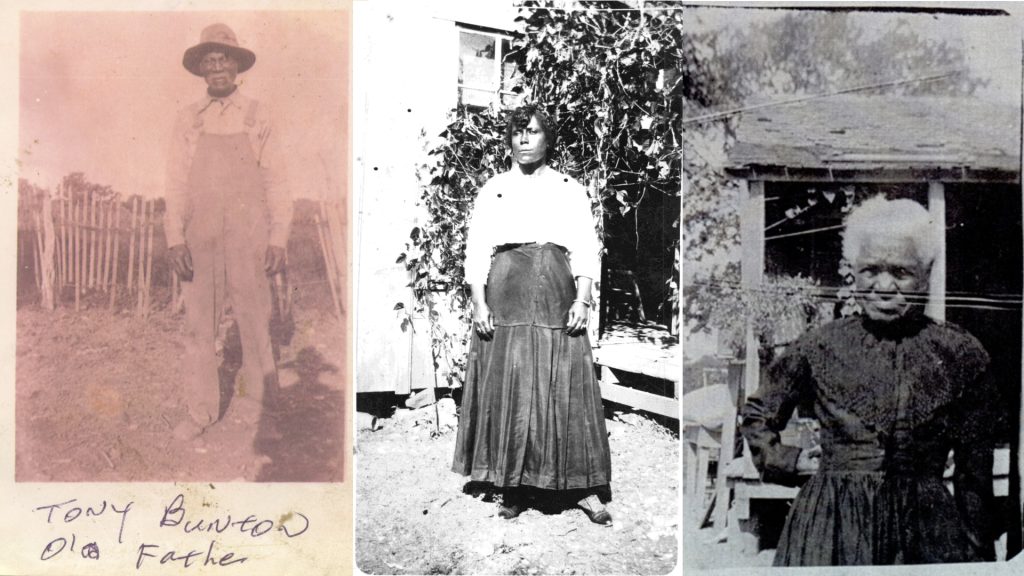

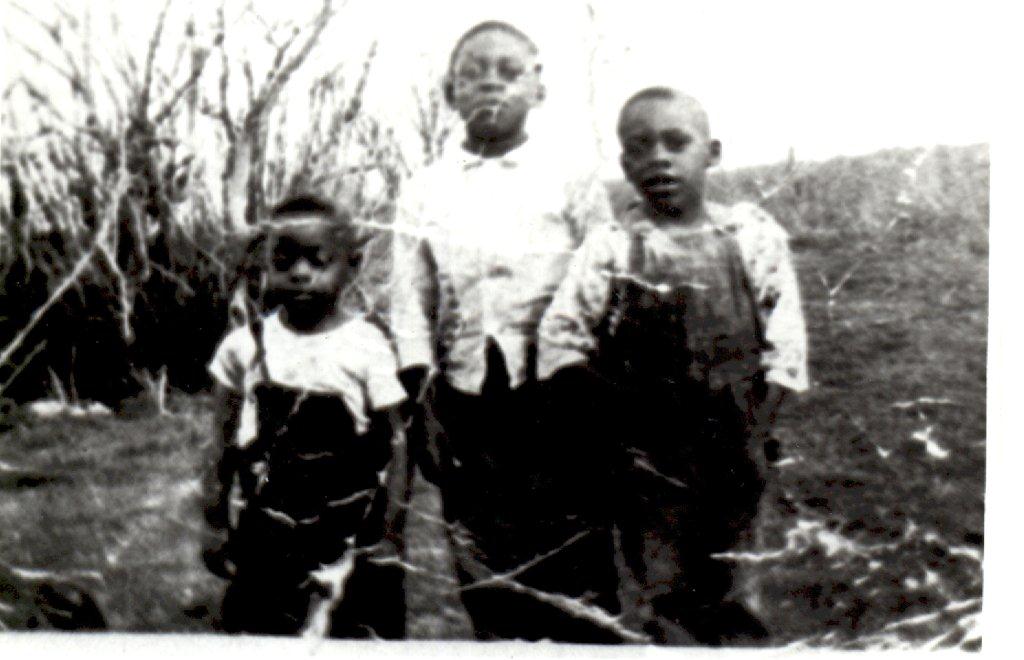

Pieces of this puzzle come from different sources: oral history interviews, archaeological evidence, archival records, and even old family photos and heirlooms. While the puzzle will never be complete, Antioch’s story has started to come together. It is a tale of sorrow and loss, but also one of hope, love, generosity, and resilience. At a time when the U.S. is deeply divided by racial strife, economic insecurity, and the uncertainties of what the future holds, the tales of our forebears serve to remind us of what is possible in challenging times.

Several years after the Civil War, 13 Black families made their way to the outskirts of what is today the small city of Buda, about 15 miles south of Austin. Like their counterparts across the South, they were deeply familiar with the arduous labor of planting cotton and corn under slavery.

The period called Reconstruction, in which the United States sought to reintegrate the former Confederate states and to address the challenges facing emancipated Blacks, offered hope for Black people that they might be able to determine their own fates. Antioch was one of over 500 “freedom colonies” established by Blacks in Texas after emancipation. Antioch’s original settlers were among the 1.8 percent of Blacks in the state who owned land by 1870. This feat was made possible through the willingness of Joseph Rowley, a White man who sold them over 300 acres of land at a time when most Whites refused to do so.

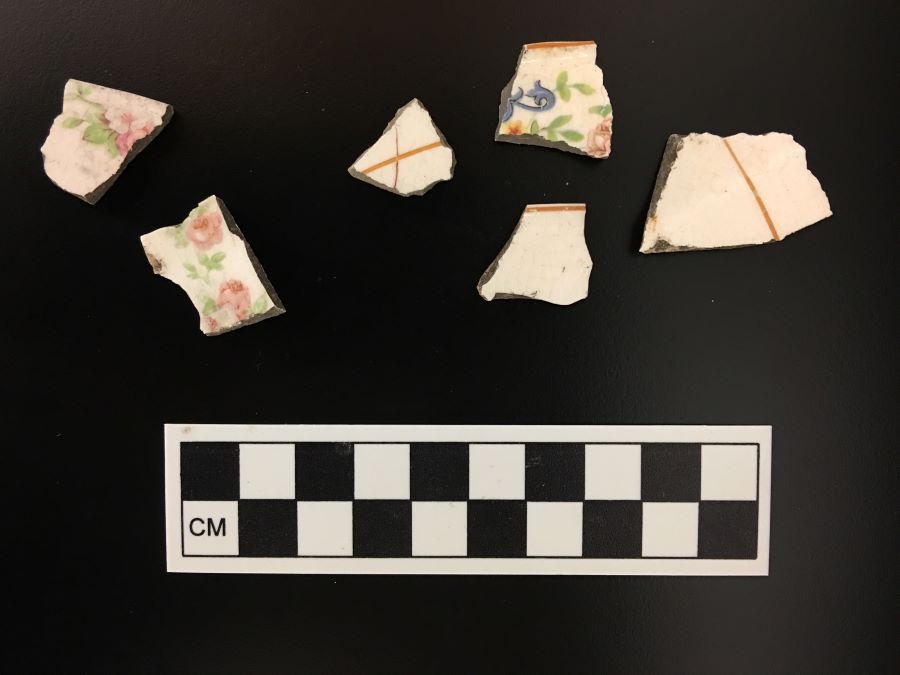

African Americans and other historically marginalized groups are often underrepresented in archival records. But archaeology can help in recovering their pasts. People from all walks of life used and discarded objects, built homes, and modified their landscapes.

My students at the University of Texas and I conducted excavations of two homesteads and the colony’s original church and school. We recovered thousands of artifacts that represented everyday life at Antioch, including glass jars used by women to can fruits and vegetables that households grew themselves and decorated ceramic tablewares that echo the importance of family dinners.

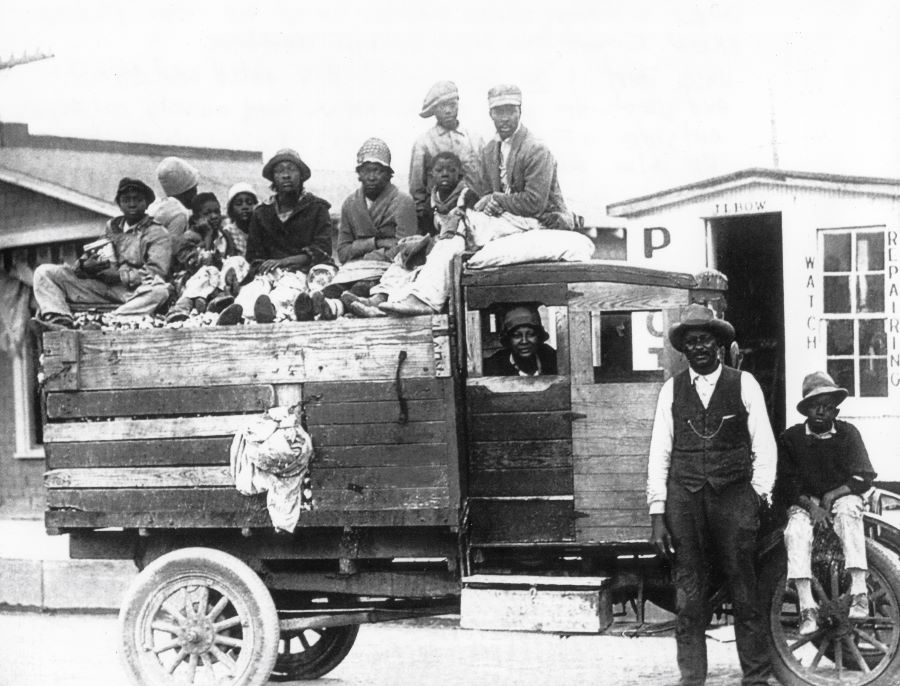

In addition, while archaeological research has helped us fill in the gaps of what transpired at Antioch, we had another important source of historical knowledge: the men and women who are descended from the colony’s original settlers. Although Antioch’s community began to decline by the 1920s as residents were swept up in the Great Migration to points north and west, some descendants remained and others returned during the 1970s to live on the land they inherited from their parents.

Prior to the excavations at Antioch, Nedra Lee, my graduate student at the time, and I interviewed 13 Antioch descendants as part of a larger project to recover the post-emancipation history of Blacks in central Texas. Ten of these individuals were raised within the colony and shared their memories of what life was like in this all-Black settlement during the Jim Crow era. Their recollections helped humanize the past by providing insights into family and community relationships. We learned about the daily indignities Black women experienced as day workers in White people’s households. Descendants recalled how women’s labor, including making the family’s clothes and raising and preparing food, helped alleviate the family’s dependence on store credit throughout the winter months.

The dig at Antioch provided us with an opportunity to trace the colony’s history into the more recent past. We discovered that while times changed, Antioch’s pioneering settlers were role models for their future generations. As the artifacts and interview quotes illuminate in the accompanying photo essay, Antioch’s residents weathered decades of racial segregation and hardship through the power of strong families, the generosity of neighbors helping one another, and a profound resilience.