Five Human Species You May Not Know About

Lea este artículo en: Español (Spanish).

We’re so used to the idea of being the only people around that it seems outlandish to think that not so long ago in our evolutionary history, multiple types of humans occupied various landscapes. The environments of the Paleolithic, or Stone Age, were dynamic. Populations moved, interacted, and sometimes even interbred. As archaeological methodologies and available technologies become more sophisticated, we’re able to “see” the lives of these human populations with more and more nuance, making the world of the Paleolithic more like a living tableau than a frozen museum diorama.

So, how many different types of humans have there been? It’s a big question, and anthropologists have yet to agree on an answer.

A big part of the debate is that there are very few specimens for anthropologists to work from. Take a moment to picture the whole spectrum of modern humans’ body sizes and shapes, and imagine trying to re-create that using the skeletons of just a handful of random individuals. Researchers have unearthed fossils from about 6,000 hominins in total. Only a handful have yielded any genetic evidence.

Researchers try to work out which ones represent novel species, sometimes from a single skull or just a finger bone. The work is hard and can be contentious.

Read more from the archives: “Were Neanderthals More Than Cousins to Homo Sapiens?“

Each scientific name bears a genus term followed by a species term. In the human family tree, the genus Homo goes back about 3 million years and includes more than a dozen named hominin species (including modern humans, H. sapiens). The extended hominin family, including the genus Ardipithecus, goes back some 6 million years.

Here are five hominins who contributed to the story of human evolution that you may be less familiar with, showing just how diverse the ancient human landscape has been.

1. HOMO RUDOLFENSIS

Homo rudolfensis is a perfect example of the pitfalls of describing a species based on limited fossil evidence. The designation is based on a single specimen—a skull (also known as the less snappy KNM-ER 1470) dated to about 1.9 million years ago from the site of Koobi Fora in what is today Kenya.

Originally, the skull was attributed to the species Homo habilis, the earliest-known member of the human genus. There were a few problems with this, though. First, the braincase of the skull was quite big. The other existing H. habilis specimens had brains around 500 cubic centimeters; H. rudolfensis had a cranium that would have accommodated about 700 cubic centimeters of brain. The H. rudolfensis specimen also has larger teeth and a smaller brow ridge than other H. habilis skulls.

Anthropologists eventually concluded that variation within a single species—even accounting for possible differences between males and females—was unlikely to explain these physical differences, and KNM-ER 1470 was given a separate species designation in 1986.

2. HOMO ANTECESSOR

The Gran Dolina Cave in Atapuerca, Spain, is a massive archaeological site, with deposits that extend down almost 20 meters and span more than half a million years. The oldest of these deposits date to around 780,000 years ago and include the remains of a hominin group that was called Homo antecessor in 1997.

The species is often described as having a mix of modern and “primitive” traits—some features are similar to those of Neanderthals and Denisovans, while others are more like Homo sapiens. A recent study of ancient proteins extracted from the dental enamel of one of the Atapuerca fossils has confirmed that H. antecessor is a very closely related “sister lineage” to modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans. All of these populations share a close common ancestor.

3. HOMO FLORESIENSIS

The only known fossils of Homo floresiensis come from Liang Bua Cave on the Indonesian island of Flores. Anthropologists also refer fondly to the species as “hobbits” due to their diminutive size: They would have stood a bit over 3 feet tall. The first remains of H. floresiensis were discovered in 2003.

These human relatives had small brains (around 400 cubic centimeters) but hunted prey on the island and made tools very similar to those made by Homo erectus, a species with much larger brains. A possible explanation for the hobbits’ small stature is a phenomenon known as insular dwarfism.

In environments with constrained resources—like an island surrounded by open ocean—species that would normally have larger body and brain sizes tend to evolve toward smaller body mass and smaller brains. A species of pygmy elephant (now extinct) that once shared the island of Flores with H. floresiensis is an example of the same process.

4. HOMO LUZONENSIS

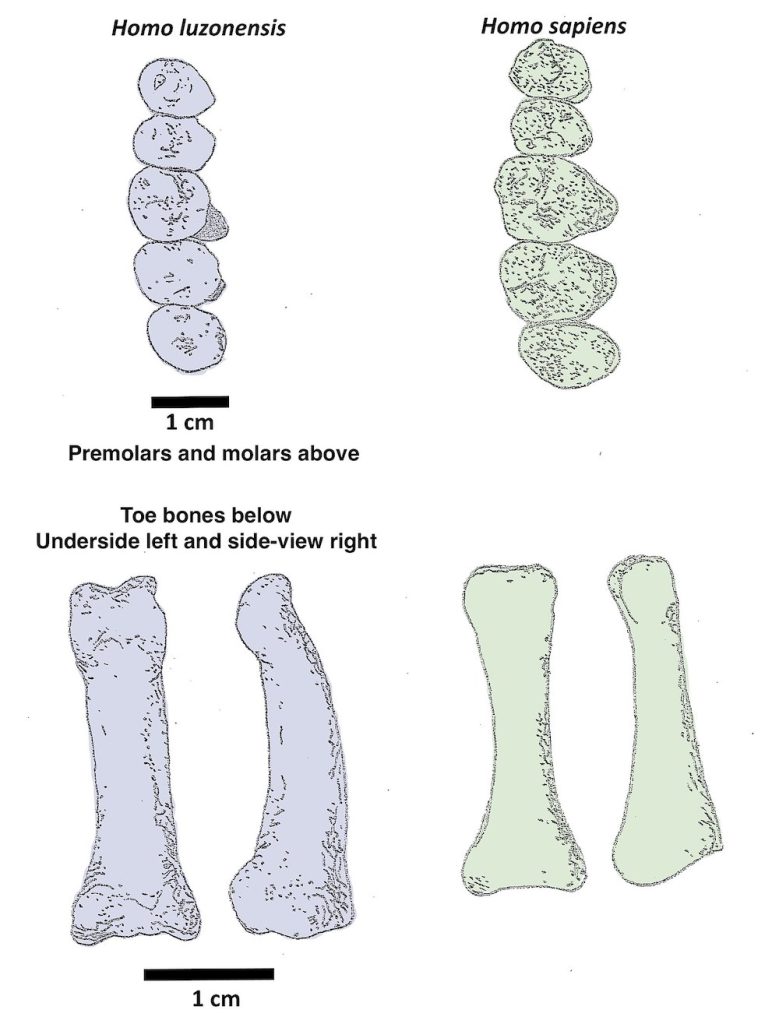

Another recently discovered island-dwelling hominin population, Homo luzonensis lived on the island of Luzon in the Philippines around 50,000–60,000 years ago. This species is represented by just 13 bones—teeth, finger, and toe bones, and a femur. These belonged to at least three different individuals.

In 2019, anthropologists determined that these bones are different enough from species like H. erectus and H. floresiensis to warrant a new species category. The finger and toe bones of H. luzonensis are especially interesting. They’re slightly curved, a feature that is shared by living species of tree-dwelling primates. This suggests that for H. luzonensis, living in the trees might still have been a part of their lifestyle.

5. HOMO LONGI (“DRAGON MAN”)

The most recently proposed hominin species comes from China, where the heavy-browed skull nicknamed “Dragon Man” was named in June. The skull was first found in the 1930s but only recently made available to scientists for analysis. It has been dated to around 146,000 years ago and is touted by its analyzers as a “long-lost sister lineage” of H. sapiens.

The eye sockets of the skull are large and blocky, the molars are sizeable (much larger than yours or mine), and the ridge over the eyes is massive. All of these are more “primitive” traits. However, the brain size is comparable to that of modern humans. This new discovery is another reminder of the difficulty of assigning a single specimen to a new species. The Dragon Man may in fact be a Denisovan—so far there’s no genetic evidence to help determine that. Wherever this individual fits on the human family tree, it’s an exciting reminder that the human past is a tangled one, and we’ve still got so much to learn.

For more of the story on some of the most recently discovered members of our extended ancient family, check out the “Who’s the New Guy” episode at The Dirt Podcast.