The Untold Story of Japan’s First People

This article is from Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

Itek eoirapnene. (You must not forget this story.)

—Tekatte, Ainu grandmother, to her grandson Shigeru Kayano

The bear head is small. Cradled in Hirofumi Kato’s outstretched palm, its mouth a curving gap in bone, the little carving could be a child’s toy, a good luck charm, a deity. It may be 1,000 years old.

Voices swirl around Kato, a Japanese archaeologist. He stands in the middle of a school gym that now serves as a makeshift archaeological lab on the northern Japanese island of Rebun. The room is filled with smells: of earth, with an undertone of nail polish, overlaid with an aroma that takes a minute to decipher—the pungence of damp bone drying.

The racket around us is different from anything I experienced as an English teacher in Japan almost 30 years ago, when my students lived up to their reputation for quiet formality. So much is going on in this gym. There is, simultaneously, order and chaos, as is the case whenever students and volunteers pad the workforce. These recreational archaeologists sit cheerfully amidst the grit, cleaning debris from sea lion scapulas with toothbrushes, even as the bones fall apart in their hands.

Kato teaches at Hokkaido University’s Center for Ainu and Indigenous Studies in Sapporo, more than 400 kilometers to the south. But since 2011, he has directed an archaeological dig here at the site known as Hamanaka II. Buried beneath the sediments, Kato and his colleagues have found clear, continuous layers of occupation that date back as far as 3,000 years before present.

The ambitious scale of this excavation—40 square meters—is unusual in Japan. Archaeology is typically focused on “telephone booth” digs, and often archaeologists are merely swooping in for rescue projects, working quickly to record what’s there, save what’s worthwhile, and clear the way for construction to begin. But at Hamanaka II, Kato has taken a very different approach. He thinks earlier archaeologists misrepresented the dynamism and diversity of Rebun and the larger neighboring island of Hokkaido. They simplified the past, lumping the story of the northern islands in with that of Honshu to the south. More importantly, they paid little attention to traces of a northern Indigenous people who still call this land home—the Ainu.

For much of the 20th century, Japanese government officials and academics tried to hide the Ainu. They were an inconvenient culture at a time when the government was steadfastly creating a national myth of homogeneity. So officials tucked the Ainu into files marked “human migration mysteries,” or “aberrant hunter-gatherers of the modern age,” or “lost Caucasoid race,” or “enigma,” or “dying race,” or even “extinct.” But in 2006, under international pressure, the government finally recognized the Ainu as an Indigenous population. And today, the Japanese appear to be all in.

In the prefecture of Hokkaido, the traditional territory of the Ainu, government administrators now answer the phone, “Irankarapte,” an Ainu greeting. The government is planning a new Ainu museum, meant to open in time for the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo. In a country known for its almost suffocating homogeneity—to outsiders anyway, and not always fairly—embracing the Ainu is an extraordinary lurch into diversity.

The Ainu arrived at this moment of pride from prejudice, through adaptation, resilience, and the sheer stubbornness of human will. The little bear head in Kato’s hand represents their anchor to the past and their guide to the future, a stalwart companion, the immutable spirit of an epic journey.

Rebun Island is 80 square kilometers of rock in the Sea of Japan. Hamanaka II snuggles between a mountain and Funadomari Bay, a basin formed by outcrops that reach out to sea like scorpion pincers.

On a clear day, Russia floats on the sea in the distance.

The site itself is a big, gaping hole about a half-hour walk from the school gym. It crawls with over 30 volunteers, from Japanese high school students to retirees from California, a diverse cast chattering away in Japanese, Russian, English, and English tinged with Finnish, Chinese, and Polish accents—another departure for Japanese archaeology. [1] [1] In the video below, archaeologists examine a particularly rich find of sea mammal bones at the Hamanaka II site. The Ainu of Rebun Island relied almost entirely on marine protein, especially sea mammal. Jude Isabella

Archaeologists have dug on Rebun since the 1950s. During a break, Kato takes me on a short tour around this corner of the island, where homes, gardens, and small fields surround the archaeological site. Laundry flutters on clotheslines and climbing roses flavor the air with a fleeting essence. We see no one aside from the archaeological crew, partly because it’s a major Japanese holiday—Obon, a day to honor the spirits of ancestors—but also because many of the islanders moved away in the 20th century, starting in the 1950s with the crash of the herring fishery and intensifying in the 1990s with Japan’s recession.

Today, fewer than 3,000 islanders remain, relying economically on tourists, fish, and an edible kelp known as konbu. Each of these makes seasonal appearances and not always in great quantities. In contrast, the giant site that Kato and his crew are digging brims with visual and tactile reminders that Rebun was once loaded with people who lived off the land and sea for thousands of years: Some gathered abalone, some hunted sea lions, and some raised pigs and dogs probably imported from Siberia. These people were the ancestors of the Ainu.

Humans first landed on Hokkaido at least 20,000 years ago, probably arriving from Siberia via a land bridge in search of a less frigid environment. By the end of the last ice age, their descendants had developed a culture of hunting, foraging, and fishing. Large-scale rice farming was a southern phenomenon; the north was too cold, too snowy. The northerners’ ancient culture persisted largely unchanged until the seventh century, when the traditional Ainu way of life became more visible in the archaeological record on Hokkaido, Kamchatka, and nearby smaller islands, such as Rebun, Rishiri, Sakhalin, and Kuril. A nature-centered society of fishers, hunters, horticulturalists, and traders emerged.

The Ainu, like their ancestors, shared their land with an important predator. The brown bears of Hokkaido, Ursus arctos yesoensis, are closely related to the grizzlies and Kodiaks of the New World, though they’re on the smallish side, with males reaching 2 meters in height and fattening to almost 200 kilograms.

In the north, the lives of the Ainu and their ancestors were closely entwined with the bears, their fiercer cousins. Where bears fished, humans fished. Where bears picked monkey pear, humans picked monkey pear. Where bears tramped, humans tramped. They were kindred spirits, and so strong was the connection between humans and bears, that it lasted across time and cultures. The people honored bear spirits through ritual for thousands of years, deliberately placing skulls and bones in pits for burial. And in historical times, written accounts and photographs of a bear ceremony show that the Ainu maintained this deep kinship.

Rebun Island’s sites are crucial to authenticating the relationship. Excavating the island’s well-preserved shell middens can reveal much more than volcanic Hokkaido with its acidic soil that eats bone remains. And it appears that ancient islanders, bereft of any ursine population, must have imported their bears from the Hokkaido mainland. Did they struggle to bring live bears to the island, via canoe? A big, seagoing canoe with oars and a sail, but still.

Kato points down a narrow alley between two buildings. At a site there, an archaeological team discovered bear skull burials dating between about 2,300 and 800 years ago. Nearby, at Hamanaka II, Kato and his colleagues uncovered buried bear skulls dating to 700 years ago. And this year, they found the little 1,000-year-old bear head carved from sea mammal bone.

The newly discovered carving is doubly exciting: It’s an unusual find and it suggests an ancient symbolism undiminished by time. The bear has likely always been special, from millennium to millennium, even as the islanders’ material culture changed and evolved long before the Japanese planted their flag there.

The environment, economy, and traditions may all metamorphose over time, but some beliefs are so sacrosanct, they are immortal, passing as genes do, from one generation to the next, mixing and mutating, but never wavering. This bond with the bears has survived much.

At age 49, with hair more gray than black, Kato is still boyish. On this hot summer day on Rebun, he sports a ball cap, an orange plaid short-sleeved shirt, and chartreuse shorts and sneakers. And as he speaks, it’s clear he has a lingering sense of injustice when it comes to the Ainu, and the curriculum he was fed in grade school.

“I was born in Hokkaido, 60 kilometers east of Sapporo,” he says. Yet he never learned the history of Hokkaido. Schools across the nation used a common history textbook, and when Kato was young, he only learned the story of Japan’s main island, Honshu.

Honshu is densely populated and home to the country’s largest cities, including Tokyo. Hokkaido, just north of Honshu, retains more natural wonder and open spaces; it’s a land of forests and farms and fish. On a map, Hokkaido even looks like a fish, tail tucked, swimming away from Honshu, leaving a wake that takes the local ferry four hours to track. Today, the two islands are physically connected by a train tunnel.

On the surface, there is nothing about Hokkaido that is not Japanese. But dig down—metaphorically and physically, as Kato is doing—and you’ll find layers of another class, culture, religion, and ethnicity.

For centuries, the Ainu lived in kotan, or “permanent villages,” comprised of several homes perched along a river where salmon spawned. Each kotan had a head man. Inside the reed walls of each house, a nuclear family cooked and gathered around a central hearth. At one end of the house was a window, a sacred opening facing upstream, toward the mountains, homeland of bears and the source of the salmon-rich river. The bear’s spirit could enter or exit through the window. Outside the window was an altar, also facing upstream, where people held bear ceremonies.

Each kotan drew upon concentric zones of sustenance by manipulating the landscape: the river for fresh water and fishing, the banks for plant cultivation and gathering, river terraces for housing and plants, hillsides for hunting, the mountains for hunting and collecting elm bark for baskets and clothes. Coaxing food from the earth is tough at the best of times, why not make it as easy as possible?

In time, the Ainu homeland, which included Hokkaido and Rebun, as well as Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, now part of Russia, joined a large maritime trade. By the 14th century, the Ainu were successful middlemen, supplying goods to Japanese, Korean, Chinese, and later Russian merchants. Paddling canoes, with planked sides carved from massive trees, Ainu sailors danced across the waves, fishing for herring, hunting sea mammals, and trading goods. A pinwheel of various cultures and peoples spun around the Ainu.

From their homeland, the Ainu carried dried fish and fur for trade. In Chinese ports, they packed their canoes with brocades, beads, coins, and pipes for the Japanese. In turn, they carried Japanese iron and sake back to the Chinese.

And for centuries, these diverse cultures struck a balance with one another.

When I lived on the southern Japanese island of Kyushu in the late 1980s, I was struck by the physical diversity of the people. The faces of my students and neighbors sometimes reflected Asian, Polynesian, or even Australian and North American Indigenous groups. The Japanese were aware of these physical distinctions, but when I asked them about the origins of the Japanese people, the answer was the same: We’ve always been here. It made me wonder what my students had learned about human origins and migrations.

Today, science tells us that the ancestors of the ethnic Japanese came from Asia, possibly via a land bridge some 38,000 years ago. As they and their descendants spread out across the islands, their gene pool likely diversified. Then, much later, around 2,800 years ago, another great wave of people arrived from the Korean Peninsula, bringing rice farming and metal tools. These newcomers mixed with the Indigenous population, and, like most farming societies, they kick-started a population boom. Armed with new technology, they expanded across the southern islands, but stalled just short of Hokkaido.

Then around A.D. 1500, the Japanese began trickling north and settling down. Some were reluctant immigrants, banished to the southern part of Hokkaido to live in exile. Others came willingly. They saw Hokkaido as a place of opportunity during times of famine, war, and poverty. Escaping to Ezochi—a Japanese label meaning “land of barbarians”—was an act of ambition for some.

Kato tells me that his family background reflects some of the turbulent changes that came to Hokkaido when Japan ended its isolationist policies in the 19th century. The feudal shogunate (military dictatorship) that long dominated Japan lost control at that time and the country’s imperial family returned to power. The influential men behind the new emperor unleashed a modernization blitzkrieg in 1868. Many of Japan’s samurai, stripped of their status, like Kato’s maternal great-grandparents, left Honshu. Some had fought in a rebellion, some wanted to start over—entrepreneurs and dreamers who embraced change. The wave of modern Japanese immigrants—samurai, joined by farmers, merchants, artisans—had begun. Kato’s paternal grandfather left for Hokkaido to raise cows.

Kato thinks his family’s story is fairly typical, which means that maybe the ethnic Japanese on Hokkaido are also more open-minded than their kin in the rest of Japan.

As insular as Japan seems to be, it has always been bound up in relationships with others, particularly with people on the Korean Peninsula and in China. For centuries, the Japanese have identified their homeland from an external perspective, calling it Nihon, “the sun’s origin.” That is, they have thought of their homeland as east of China—the land of the rising sun. And they have called themselves Nihonjin.

But the word Ainu signifies something very different. It means “human.” And I’ve always imagined that long ago, the Ainu gave entirely natural replies to a visitor’s questions: Who are you and where am I? The answers: Ainu, “we are people”; and you are standing on “our homeland,” Mosir.

The Ainu call ethnic Japanese Wajin, a term that originated in China, or Shamo, meaning “colonizer.” Or, as one Ainu told a researcher: “people whom one cannot trust.”

Back at the dig at Hamanaka II, Zoe Eddy, a historical archaeologist from Harvard University, stands atop piles of sandbags, surveying the crew. She’s one of a handful of Ph.D. candidates Kato relies on to manage the volunteers and students. She flips between Japanese and English, depending on who is asking a question.

“Is this something?” I ask, pointing with my trowel to a curved hump, covered in sandy soil.

“Maybe sea lion vertebrae? And it might be part of that,” she says, pointing to another bump a couple of handbreadths away. “Just go slow.”

Someone else calls out and she hustles over to assist. Eddy splits her time between Boston, Washington, D.C., and Sapporo. The tall, curly-haired brunette stands out; central casting circa 1935 would have hired her to play the role of feisty female archaeologist in some exotic locale.

Eddy’s Ph.D. research focuses on cultural representations of bears among the Ainu. “You can’t swing a dead cat without hitting a bear,” she says of Hokkaido’s obsession with bear imagery. Over sips of sake later, she describes her surprise the first time she visited Sapporo, in 2012, and spotted a plastic figurine of Hokkaido’s brown bear. It had a corn cob in its mouth. Eddy puzzled over it. Like dairy cows, corn is not indigenous to the island. “I thought, that’s odd, that’s really strange,” says Eddy. “Isn’t the bear Ainu?”

Yes, and no, she learned.

To the Ainu, the bear has a body and soul; it’s a ferocious predator that roams the mountains and valleys, and it’s a kamuy, a “god.” Kamuy are great and small. They are mighty salmon and deer, humble sparrows and squirrels, ordinary tools and utensils. Kamuy visit the earth, have a relationship with humans, and if respected, they return again and again to feed and clothe humans. It’s a sophisticated belief system where both living and nonliving things are spirit beings, and where interspecies etiquette is central to a good life. To maintain a healthy relationship with the kamuy, Ainu artists traditionally represent the world in the abstract, creating pleasing designs meant to charm the gods—the transcendent symmetrical swirls and twirls of a kaleidoscope, not banal figurines. Making a realistic image of an animal endangers its spirit—it could become trapped, so Ainu artists did not carve realistic bears that clenched corn, or anything else, in their teeth.

But art has a way of adapting to the zeitgeist. The typical Ainu bear today, a figurative bear with a salmon in its mouth, has a distinct German influence. “Somebody probably said, ‘Okay, the Germans like this,’” Eddy says. Ainu artists adapted after the Meiji Restoration: They gave tourists the iconic brown bears of the Black Forest that no longer existed. This pivot was a pragmatic answer to their culture’s precarious situation.

Like all island people, the Ainu had to deal with opposing realities. For much of their history, new ideas, new tools, and new friends flowed from the sea, a vital artery to the outside world. But the outside world also brought trouble and sometimes brutality.

The first serious blow to Ainu sovereignty landed in the mid-1600s, when a powerful samurai clan took control of Japanese settlements in southern Hokkaido.

Japan had a population of roughly 25 million at the time—compared, for example, with England’s 5 million—and it was as hungry for mercantile success as most European countries. Across the globe, the chase was on for profitable voyages to distant lands, where merchants determined the rules of engagement, most often through force, upending local economies, trampling boundaries. Eager for profit, Japanese merchants dumped their trading relationships with the Ainu. Who needed Ainu traders when the resources were there for the taking—seals, fish, herring roe, sea otter pelts, deer and bearskins, strings of shells, hawks for falconry, eagle feathers for arrows, even gold?

“This is so not a uniquely Ainu story,” says Eddy, who traces some of her ancestry to the Wendat, an Indigenous group in northeastern North America. She thinks it’s important to remember all the violence that colonization entailed for Indigenous people. “Imagine one year where everything changes for you,” she says. “You have to move somewhere, you can’t speak your language, you can’t live with your family, you watch your sister raped in front of you, you watch your siblings die of starvation, you witness your animals slaughtered for fun.”

Ainu. Wendat. Similar plots and themes, but each unique in the telling.

In the late 1800s, the Japanese government formally colonized Hokkaido. And Okinawa. And Taiwan. And the Sakhalin and Kuril Islands. The Korean Peninsula, and eventually, by the 1930s, Manchuria. The Japanese went to war with Russia and won, the first time an Asian country beat back the incursions of a European power in living memory. On Hokkaido, the Japanese government pursued a policy of assimilation, hiring American consultants fresh from the drive to assimilate North American Indigenous people. The government forced the Ainu into Japanese-speaking schools, changed their names, took their land, and radically altered their economy. They pushed the Ainu into wage labor, notably in the commercial herring fishery after Japanese farmers discovered fish meal was the perfect fertilizer for rice paddies.

For much of the 20th century, the Ainu narrative created by outsiders revolved around their demise. But something else caught the attention of Japanese colonists and others traveling to Mosir: the Ainu’s relationship with bears.

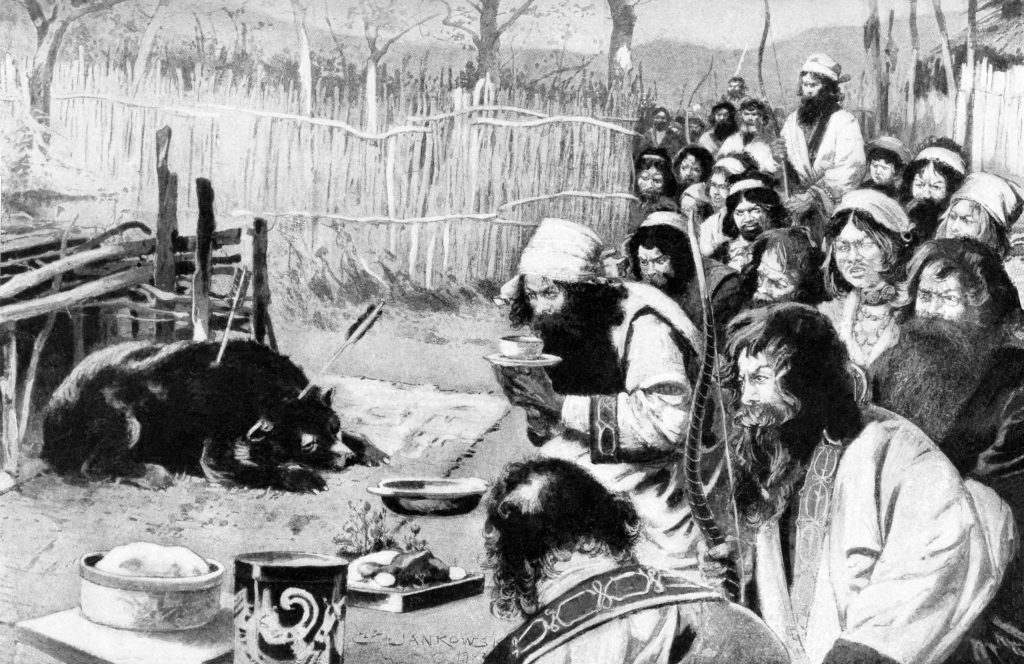

To the Ainu, the bear god is one of the mightier beings in the parallel spirit homeland, Kamuy Mosir. After death, bears journeyed to this spirit land, giving their meat and fur to the people. To honor this generosity, the people sent the bear’s spirit home in a special ceremony, iyomante.

In winter, Ainu men searched for a denning mother bear. When they found her, they adopted one of her cubs. A kotan raised the cub as one of their own, the women sometimes nursing the young animal. By the time it was so big that 20 men were needed to exercise the bear, it was ready for the ceremony. For two weeks, men carved prayer sticks and bundled bamboo grass or mugwort to burn for purification. Women prepared rice wine and food. A messenger traveled to nearby kotans to invite people to attend.

Guests arrived a day before the ritual, bearing gifts. At the start of the ceremony, an elder offered a prayer first to the goddess of the fire and hearth, Fuchi. The elder led the men to the bear cage. They prayed. They released the bear to exercise and play, then shot him with two blunt arrows before strangling and beheading him, freeing the spirit. People feasted, they danced, they sang. They decorated the head and an old woman recited sagas of Ainu Mosir, the floating world that rested on the back of a fish. She ended Scheherazade-like, on a cliffhanger, a sly bid to lure the god back next year to hear the rest of the story. Finally, they placed the bear’s head on the altar outside the sacred window.

Archers drew their bows, and the whistling of ceremonial arrows accompanied the bear god home.

Viewed from today, the ritual of raising and sacrificing a dangerous predator seems both exotic and powerfully seductive. And in the minds of many people today, the bear and the Ainu have become entwined in a modern legend. Separately they are animals and people, together they have attained a near-mythical status.

Eddy sees the modern transformation of the Hokkaido bear, from sacred being to mascot, as a symbol of Ainu resilience under the pressure of Japanese domination. For archaeologists, the bear testifies to the deep antiquity of the Ainu and their ancestors in Hokkaido. And for the Ainu themselves, their ancient bear god gave them an unlikely toehold in the modern economy.

“It would be easy to treat the [realistic] carvings as an example of the sad death of traditional Ainu culture,” Eddy says. “To me, it’s a real mark of creativity, of adaptability, and resilience in the face of just this complete devastation of older economies.”

The Ainu did not get rich, or respect, but they held on.

In the Ainu Museum in Shiraoi, south of Sapporo, a cute cartoon bear in a red T-shirt adorns a sign advertising bear treats for 100 yen. Nearby, inside a cage, a real bear slurps down one of the treats.

The museum was built in 1976, after a flurry of civil rights activism, and today three brown bears are on display in separate cages. Little kids, chattering away, feed a cookie to one via a metal pipe, then leave. The bear looks over at the three of us: Mai Ishihara, a graduate student at Hokkaido University; Carol Ellick, an American anthropologist who has worked with the Ainu; and me.

Almost 130 million people live in Japan today, but wild bears still roam the country’s forested mountains and valleys. Just a couple of months before my visit, a bear attacked and killed four people foraging for bamboo shoots in northern Honshu. But these conflicts are not new. One of the worst bear encounters took place in 1915, when Japan was in full colonizing swing: A bear attacked and killed seven Wajin villagers in Hokkaido. Their deaths were tragic, but perhaps inevitable. Wajin homesteaders had cut down large swaths of forest for firewood so they could render herring into fertilizer. As the landscape changed, the relationship between humans and bears changed, too. Colonization seems so straightforward on paper.

There is no iyomante today. The bears in the Ainu Museum are there for the tourists. We’re greeted by the museum’s educational program director, Tomoe Yahata, wearing a dark blue jacket embroidered with the swirls and twirls of traditional Ainu designs over a black T-shirt and jeans. Her shoulder-length black hair frames a genial face. As we lunch by a lake, I see that Yahata’s charm is her genuine joy: If bluebirds were going to sing and circle around anyone here, it would be Yahata.

Yahata tells us that both her parents are Ainu, which is unusual; probably 90 percent of all Ainu have ethnic Japanese in their background. The museum official makes no apology for being Ainu—she is proud. For Ishihara, listening to Yahata is a bit of a revelation.

Ishihara is one-quarter Ainu, a fact her half-Ainu mother kept secret from her for much of her childhood. Physical traits do not a people make, but the Ainu are expected to have wavy hair and a certain stockiness to mark them as different. Neither Yahata nor Ishihara look anything other than Japanese. Ishihara, artfully dressed and striking in high-wedge sandals, with a woven cap jauntily perched on her head, would fit into any big metropolis. Independently, both women began exploring what being Ainu meant to them when they were in college.

Yahata says college trips to Hawai‘i and other places where Indigenous groups lived changed her. “People there, in Hawai‘i … they’re so happy and so proud of [being Indigenous].” After her college travels, she says, she wanted “to become like that.”

The two women joke about how Japanese people tend to think the 16,000 self-identified Ainu live only on salmon and food from the forests in rural Hokkaido. “Ainu people can go to Starbucks and have coffee and be happy!” says Yahata. Ellick, whose anthropologist husband Joe Watkins is a member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, laughs and jumps in. “Joe said when his children were little … his son asked if there were still Indians! And his son is American Indian. So Joe had to stop and say: ‘Okay, so let me explain something to you. You are Indian!’” Another round of laughter and disbelief.

Then, almost on cue, we ask Yahata: “How do you be Ainu?” In reply, she tells us a story about buying a car.

When Yahata and her non-Ainu husband purchased a used Suzuki Hustler, they decided to welcome the little blue car with the white top into their lives as a traditional Ainu family would welcome a new tool. They conducted a ceremonial prayer to the car’s kamuy. On a cold, snowy December night, Yahata and her husband drove the car to a parking lot, bringing along a metal tub, some sticks of wood, matches, sake, a ceremonial cup, and a prayer stick.

The couple tucked the car into a parking space and made a little fireplace with the metal tub and wood. “Every ceremony needs to have fire,” Ishihara translates. For half an hour, the couple prayed to the car kamuy. They poured sake into an Ainu cup borrowed from the museum and dipped a hand-carved prayer stick into the cup to anoint the car with drops of sake: on the hood, the roof, the back, the dashboard, and each tire.

Their prayer was a simple one: keep them and other passengers safe. Of course, adds Yahata with a smile, they got insurance.

We all laugh, again. The ceremony was so much fun, Yahata says, that the couple held another when they changed from winter tires to summer tires.

Ishihara, Ellick, and I agree—each of us wants to be like Yahata. Content and proud and full of joy. Studying the past and present of the Ainu reveals what we all know deep down—symbols and rituals and belonging are essential to our humanity. And that doesn’t change, no matter the culture: We are all the same, and we are all different.

The next morning, Ishihara, Ellick, and I head off to Biratori, a neighboring town where a third of the population is Ainu. During the two-hour drive, Ishihara shares a memory—the moment she found out about her ethnic heritage.

She was 12 years old, attending a family gathering at her aunt’s house in Biratori. No other children were present, and the adults began talking about their marriages. “Some of my uncles said, ‘I don’t tell my wife’s family that I have this blood.’” But Ishihara’s mother, Itsuko, said, “I have told everyone that I am minzoku.” Ishihara thinks that they avoided using the word Ainu because it was just too traumatic. Instead, they spoke about being minzoku, which roughly translates to “ethnic.” Ishihara didn’t know the meaning of the word, so she asked her mother. The first thing her mother said was, “Do you love your grandmother?” Ishihara said yes. “Do you really want to hear about it?” Ishihara did. Her mother answered: “You have Ainu heritage.” She didn’t want her daughter to discriminate against Ainu people. But Ishihara’s mother also told her not to tell anyone. “So I know it’s bad. I can’t tell my friends or my teachers.”

We drive through a verdant valley of trees, grasses, and crops fed by the Saru River, a waterway once rich in salmon that cascades from the mountains and empties into the Pacific Ocean. Indigenous sites dot the river, some stretching back 9,000 years. When Wajin built a trading post along the Saru in the 19th century, the Ainu brought them kelp, sardines, shiitake mushrooms, and salmon in exchange for Japanese goods. The Ainu fished in the ocean in the spring, harvested kelp in the summer, and caught salmon in the river in autumn. In the winter, the men repaired and maintained their fishing boats, while women wove elm bark into clothing and fashioned leather out of salmon skin for boots.

The Saru Valley is also where a famous Ainu leader, Shigeru Kayano, took a stand against the Japanese government. In the 19th century, a samurai took Kayano’s grandfather to work in a herring camp: The homesick boy chopped off one of his fingers, hoping his Wajin masters would send him home. Instead, they told him to stop crying. Kayano never forgot the story. In the 1980s, the Japanese government expropriated Ainu land along the Saru to build two dams: Kayano took the government to court. He fought a long legal battle and finally won a bittersweet victory. In 1997, the Japanese judiciary recognized the Ainu as an Indigenous people—a first from a state institution. But as the parties battled in the courts, dam construction went ahead. Kayano continued to fight for his people’s rights. As the case went through the courts, he ran for a seat in Japan’s parliament, becoming its first Ainu member in 1994.

As we drive through Biratori, Ishihara remembers coming here often as a child to visit her grandmother, aunts, and uncles. A great-aunt still lives here. The older woman was forced to move to Japan from Sakhalin, which was seized by Russia after the Second World War. For Ishihara, this is hard-won information. She has been slowly piecing together the family’s history over the past seven years, through conversations with her great-aunt and her mother, Itsuko.

“If I don’t know the history of what we’ve been through, how do I understand the present?” Ishihara wonders out loud. “My mother says Japanese people look at the future and never the past. What I’m trying to do drives my mother crazy, but her experience is so different.”

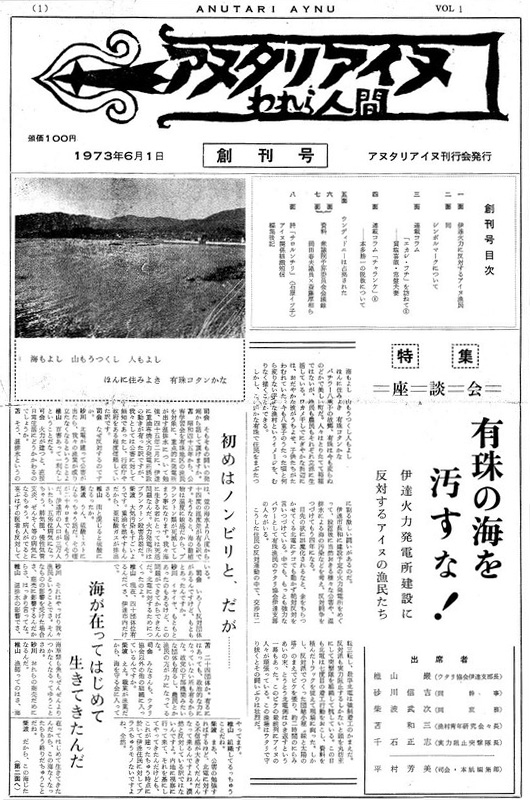

Itsuko and her cousin Yoshimi were just girls when newspaper headlines routinely proclaimed the end of the Ainu. In 1964, one newspaper headline announced, “Only One Ainu in Japan,” fake news long before anyone called it that. Indignant about such treatment in the press, Yoshimi and Itsuko launched their own publication called Anutari Ainu (meaning “we humans”) in June 1973. Working out of a tiny Sapporo apartment, they and a small collective of mostly women became the voice of a new Ainu movement, producing a periodical that explored Indigenous social issues through articles, poetry, and art. But in less than three years, this voice was silenced.

Ishihara is reluctant to give more details, particularly of Yoshimi’s story because, “It’s not mine to tell.” But search scholarly papers and books about the Indigenous rights movement in Japan, and Yoshimi, today close to 70, is part of the narrative. Neither Yoshimi or Itsuko played a role, however, in the political violence on Hokkaido carried out by radical members of Japanese counterculture, a movement with analogs across the globe—disaffected youth pissed off at the political status quo. The dissidents first tried unsuccessfully to assassinate the Wajin mayor of Shiraoi in 1974. Then a group bombed a Hokkaido government building in 1976, killing two and injuring 90. Suspicion fell on the Ainu community, and the police harassed and abused Ainu activists. Officers raided the Anutari Ainu office. Later, government officials identified the terrorists as Wajin radicals, who sympathized with the Ainu. But the Ainu community was horrified.

No wonder Itsuko and Yoshimi retreated from the movement—yet again, outsiders had hijacked their narrative, ignoring who the Ainu truly were and what they wanted.

Ainu artist Toru Kaizawa stands among a group of teens at the Nibutani Ainu Cultural Museum in Biratori. A prominent carver, Kaizawa is talking about Ainu art traditions. The kids, who traveled here from suburban Tokyo, are enjoying themselves—especially when they all begin playing mouth harps they just made with the artist’s help. Kaizawa smiles.

Artworks, mostly carvings, line the shelves of the museum shop. Here there are no realistically carved bears, only the abstract whirls and waves of the Ainu’s ancient cultural aesthetic.

The Nibutani neighborhood in Biratori has a population of about 500: nearly 70 percent are Ainu. “It’s a nice place to live,” says museum curator Hideki Yoshihara. Its valley still produces a wealth of food—20 percent of Hokkaido’s tomato crop grows here—and the bucolic pastures of cattle and horses offer a peaceful vista to tourists looking for peace and quiet. But outsiders have to want to come to this rural enclave. No tour buses swing through town. Nearly half of the annual visitors arrive from Europe and North America: They’re tourists who are comfortable renting a car and exploring on their own, often seeking out Ainu culture. [2] [2] In the video below, an Ainu dance troupe performs for tourists in a traditional home at the Ainu Museum in Shiraoi. The dancers wear the elaborately embroidered clothes traditional among their ancestors. The patterns of swirls and twirls are typical of Ainu designs, and are meant to converse with their ever-present gods. Jude Isabella

Over lunch, Yoshihara explains that the Nibutani museum is unique in Japan: It’s owned and operated by the people of Biratori. Many are descendants of the people who created the fish hooks, the dugout canoes, the salmon skin boots, the intricately carved knife handles and prayer sticks in the display cases. Kaizawa, the man talking to the high school students, is the great-grandson of a renowned 19th-century Ainu artist from Nibutani.

After the students leave, Kaizawa takes us to his studio, which sits in a cluster of artists’ workshops near the museum. Inside are tools, blocks of wood, finished pieces, and all sorts of art books—including a book from the popular manga series The Golden Kamuy, which features Ainu and Japanese characters. The cover depicts a man clutching a traditional Ainu knife—it’s based on a real object made by Kaizawa.

A few years before The Golden Kamuy came out, a prominent Japanese nationalist, artist Yoshinori Kobayashi, published a manga challenging the idea of the Ainu people and indigeneity in Japan. Kobayashi and other nationalists believe that all Japan belongs to just one founding ethnic group: the Japanese. I haven’t met any nationalists on this trip, at least not that I know of. But Kobayashi gave them a popular voice in the 1990s, when Japan’s economic bubble burst and the disenfranchised sought a target for their anger: Koreans, Chinese, Ainu.

Even so, the government is moving forward on its Ainu policy today, if slowly. It has yet to issue an official apology to the Ainu, or recognize Hokkaido as traditional Ainu territory, or even rewrite textbooks to reflect a more accurate history of Japanese colonization. One government official I talked to explained that the Japanese and Ainu had a very short history of officially living together. If the government were to offer a public apology, the Japanese people would be shocked. The first step would be to let people know of the Ainu, then apologize.

And that’s partly the problem: How do the Ainu assert their modern identity? Ishihara says it’s a question that she often asks herself. When she tells friends and colleagues about her family background, they often respond by saying that they don’t care if she is Ainu—something that makes her wince. “It’s like saying, ‘despite the fact you are of despicable Ainu blood, I like you anyway,’” she says.

And this reaction may be the reason why the number of self-identified Ainu dropped from almost 24,000 to 16,000 in less than a decade, from 2006 to 2013. It’s not as if claiming Ainu ancestry comes with many perks. Compared with ethnic Japanese, the Ainu have less education, fewer job opportunities, and lower incomes. The main thing that being Indigenous offers to the Ainu is pride.

In his studio, Kaizawa opens an art book. He thumbs through the pages until he finds what he is looking for. Then he passes the book over to me. On the glossy paper, I see a wood carving of a plain jacket, zipper partially open, revealing a swirl of abstract Ainu patterns hidden inside. It’s one of Kaizawa’s most important works.

The Japanese never erased, never destroyed the Ainu’s immutable spirit, an identity that runs soul deep.