It’s Time to Replace “Prehistory” With “Deep History”

When you think of “prehistory,” what images come to mind? Dinosaurs roaming ancient landscapes? Saber-toothed tigers on the hunt? Humans huddled in caves. Prehistory may seem like a straightforward concept—but is it really that simple?

For centuries, archaeologists have defined prehistory as a time before writing, often using the “three-age system” to neatly divide prehistoric times into the Stone, Bronze, and Iron ages. First introduced by Danish archaeologist Christian Jürgensen Thomsen in the 19th century, the system implies a linear path from “primitive” to “advanced” to describe technological progress. [1] [1] Researchers primarily applied this system to Eurasia and Africa, but other evolutionary frameworks have been applied not only to those regions but also to the Americas. This framework has all manner of trouble—from narratives driven by assumptions of the straight-line rise and fall of societies, to an obsession with “lost” civilizations, to the belief that older cultures are harder (and therefore more prestigious) to “discover.”

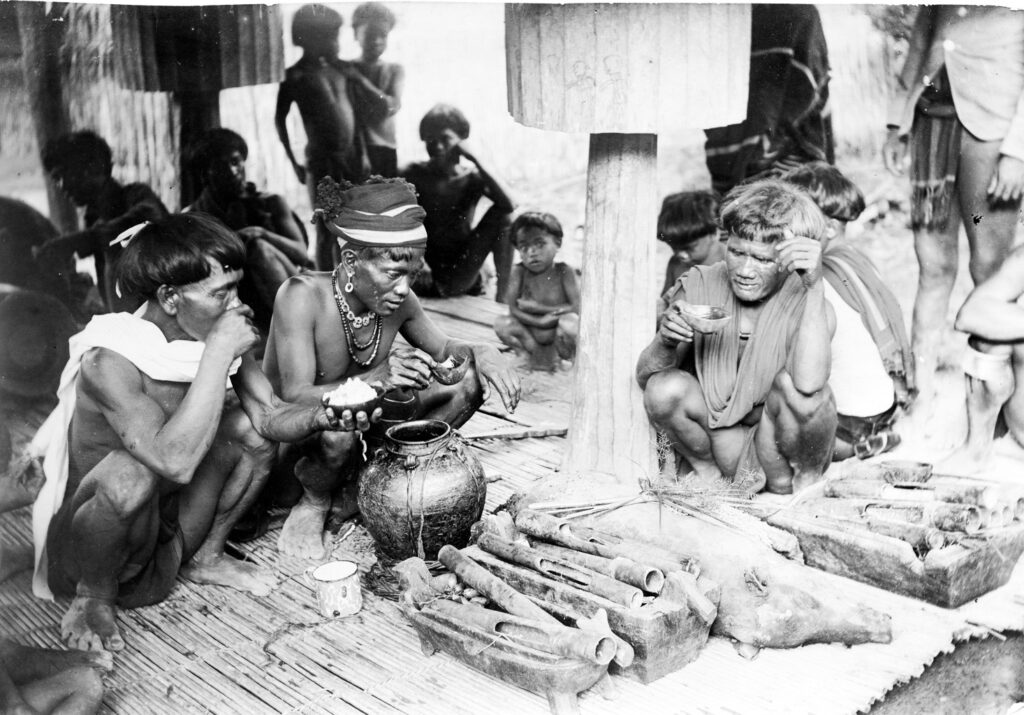

As archaeologists working in Southeast Asia, we assert that this Eurocentric system distorts our shared understandings of the past, often ignoring the ongoing development of Indigenous cultures and societies in the region and elsewhere. Instead, we advocate for “deep history.” This approach to archaeological research places value on the continuous cultural and social development of humans. It focuses on Indigenous knowledge systems, diverse Oral Histories, and a wide range of belongings and objects to expand our understanding of the past.

INDIGENOUS HISTORIES in the Philippines

As a case in point, picture the iconic rice terraces carved into steep slopes in the mountainous Cordilleras region of the Philippines.

The Indigenous Ifugao people designed these terraces that cascade downward like giant steps to harness water from mountain rivers and springs to cultivate rice. In the early 1900s, pioneering U.S. anthropologists who visited the region assumed the terraces were more than 2,000 years old—without any scientific support—simply based on the range and depth of their appearance. However, our research revealed that these iconic terraces are actually only 400 years old.

It wasn’t the Ifugao who argued that the terraces are 2,000 years old, it was the archaeologists and historians, explains co-author Marlon Martin, chief operating officer of the Save the Ifugao Terraces Movement, a heritage conservation and education organization. The Ifugao know that their terraces are old—well, my grandmother is old—so we have a different way of defining what is old, Martin adds, referring to the way Ifugao measure age based on generations, not specific numbers of years.

During the first phase of our archaeological fieldwork, conducted from 2012 to 2016, we uncovered plant and animal remains, ceramics, village pavement structures, and human remains that suggested rice cultivation began only in the 17th century. We argue that the Ifugao, known for their sophisticated agricultural practices and communal land management, crafted these terraces as a form of resistance against Spanish colonization of what became the Philippines that began in the 16th century.

The rapid transition from taro cultivation to wet-rice production suggests an influx of Ifugao lowland rice producers into the highlands. This shift, along with the construction of extensive terraces, enabled the Ifugao to consolidate their economic and political power in the highlands. Through self-sustaining agricultural practices rooted in community, the Ifugao largely managed to avoid direct Spanish colonial rule that lasted elsewhere in the Philippine archipelago through the late 19th century.

“The terraces are not just structures,” said Uncle Jun Dait, a local Ifugao community member, in a 2012 interview, “they are a demonstration of our knowledge of the environment, showcasing our ability to adapt and thrive through sustainable practices that have been honed over generations.”

The rice terraces illustrate the importance of challenging dominant narratives about the Ifugao people as static and unchanging. For years, scholars argued that the Ifugao community successfully resisted colonization due to their isolation in the highlands. But our research indicates the Ifugao have always been a dynamic and resilient people who have responded and adapted to centuries of cultural and environmental change. The discovery of trade ware ceramics from China, Japan, and elsewhere in Southeast Asia during the Spanish colonial period further underscores the interconnectedness and dynamism of Ifugao society. Today the Ifugao people continue to cultivate these iconic rice terraces as part of their cultural heritage and livelihoods.

CAMBODIA BEYOND ITS COLONIAL PAST

In Cambodia, a similar challenge exists regarding colonial interpretations of Angkor Wat, the world’s largest religious monument.

The impressive architectural feat first emerged as a Hindu temple during the Angkorian Khmer Empire, a powerful civilization that existed from the 9th to 15th centuries. The temple continued to thrive as a Buddhist pilgrimage site well beyond the 15th century, but this often gets lost in the colonial archaeological record.

Under French colonial rule in the mid-19th century, France claimed to be the “legitimate heir” of Angkor, treating it as a relic of the distant past. Colonial interpretations tended to highlight Angkor’s Hindu origins, framing it as representing Cambodia’s golden age, while dismissing later Buddhist developments as foreign influences. This timeline reinforces a story of decline rather than transition from the Hindu to Buddhist periods. It also reinforced the image of French archaeologists as saviors of a “lost” civilization, while downplaying the fact that Cambodians actively embraced and contributed to the spread and integration of Buddhism into their society.

The French colonial practice of naming kings in chronological order using Roman numerals further obscured the continuous presence of Cambodian engagement with Angkor Wat. Royal naming conventions persisted well into the 16th and 17th centuries but were spelled using local Khmer grammar and language. Over time, the colonial numerical system disconnected post-Angkorian kings from the Angkorian period, rendering the post-Angkorian Khmer invisible. The absence of these names in official archaeological records and history textbooks diminishes the continued influence of post-Angkorian Khmers on Angkor Wat.

Today, as Cambodia moves beyond its colonial past, Cambodian archaeologists have pushed to develop local expertise in archaeology and conservation. Technological advancements like lidar—which uses laser beams transmitted from aircraft or drones to create three-dimensional maps—have unveiled hidden structures within Angkor, revealing a far more complex understanding of its use and purpose.

These findings show that Angkor Wat was still inhabited throughout the 17th century, long after it was thought to be abandoned in the 15th century. European and local accounts both confirm it remained a busy Buddhist pilgrimage site. A 17th-century Japanese map shows it as a thriving religious center.

TOWARD A DEEPER HISTORY

It is time to admit that the three-age system never worked in Southeast Asia—and beyond it—to accurately describe the rich and diverse pasts of Indigenous peoples. “Prehistory” is not composed by a simple linear story.

We hope the interested public begins to appreciate this new way of thinking about the past as archaeologists push beyond the limits of the three-age model to conduct research that emphasizes the ongoing presence of Indigenous peoples and their diverse oral and cultural traditions. Incorporating local chronologies and perspectives allows for a more accurate, comprehensive, and respectful representation of Southeast Asia’s heritage and that of other regions.

Rejecting the three-age system also requires a shift in thinking from a linear progression of technological stages to a more holistic understanding of cultural change. This means placing more value on textiles, ceramics, and wood as significant technological objects of innovation. By expanding the range and depth of material evidence to indicate cultural changes, the unique advancements and contributions of societies can be better understood.

The adage “older is better” is a relic of outdated, Eurocentric thinking. It should not be the passage of time that defines significance but the stories we uncover along the way. As archaeologists and communities continue to unearth the past, we must remember that history is not simply a record of the ancient; it is deeply human, and history truly begins with the emergence of humanity.

The pursuit of deep history offers a more inclusive way to understand the full scope of human experience and cultural development.