What the Archaeology of Night Reveals

As recently as a few decades ago in the Western world, stars dazzled humans with their brightness and the Milky Way could be seen spanning the far reaches of the heavens as night deepened into an unspeakable darkness. In the 21st century, such a scene is becoming a rarity across many parts of the globe as we light up the night like never before.

Today our experience of the night differs significantly from that of our ancestors. Before they mastered fire, early humans lived roughly half their lives in the dark. The only night light they had came from the moon when skies were clear. Then, when humans began to gain some control over fire use (probably around 400,000 years ago), everything changed. From that point on, most people have had access to some form of “artificial” light, at least occasionally. Thus began our persistent efforts to light up the night. Even people who lived relatively recently—those with candles, oil lamps, and early electricity—were far more familiar with darkness than we are today. Their nocturnal world simply wasn’t as bright as ours.

But what have we gained by illuminating the night? Has anything been lost in our efforts to banish darkness? Were people, and the world, better off when it was darker?

The night has always fascinated people, for it brings with it a simultaneously feared and revered part of our existence. Yet the scientific journey into understanding ancient nights has been long in coming: Only recently have archaeologists begun to research what life was like after dark in the ancient world.

A few years ago, when we began thinking about the night lives of our ancestors, we found little academic work on the subject. The more we thought about the nocturnal, whether it was during the Paleolithic (which co-author April Nowell studies), or during Classic Maya times (which co-author Nancy Gonlin researches), the more we realized that very little research had been explicitly conducted on it. That is when we embarked on the process, with the assistance of many of our fellow archaeologists, of putting together the book Archaeology of the Night (2018), which we co-edited.

Ancient nocturnal habits were numerous and were like the many kinds of nightly activities in which we modern humans engage: sleeping, sex, stargazing, work, ceremonies, secret meetings, and so on.

Take the ancient Romans, for example. If you think that a noisy nightlife is a hallmark of the modern world, think again! Ancient Rome was a busy and often loud place. Wheeled vehicles provisioned the city’s taverns and took away its waste, and people partied until dawn during festivals, prompting one poet to write, “The laughter of the crowd passing by awakens me and all Rome is at my bedside.” Rome’s citizens often took advantage of the cover of darkness to pee over their balconies or dump objects into the streets, and to engage in crimes ranging from disturbing the peace to assault. A roving band of police rounded up these criminals, and the individual in charge of this law enforcement squad—a man who had been up all night—was also the judge who sentenced them the next morning for their crimes.

Ancient Rome reminds us that something as simple as sleep is not the same everywhere and in every time period. How we sleep, where, when, how much, on what, and with whom we sleep all have cultural aspects. Cross-cultural night studies challenge what we take to be universal and natural: Twenty-first-century Westerners think that sleeping for eight hours in a row is a good thing, but a Roman example shows that concepts such as normal sleep patterns are, in fact, culturally defined. A “first sleep” of a few hours and then a “second sleep” was a common pattern. In between those times, ancient Romans engaged in some other activity for a short time, such as deep contemplation, prayer, sex, or reading.

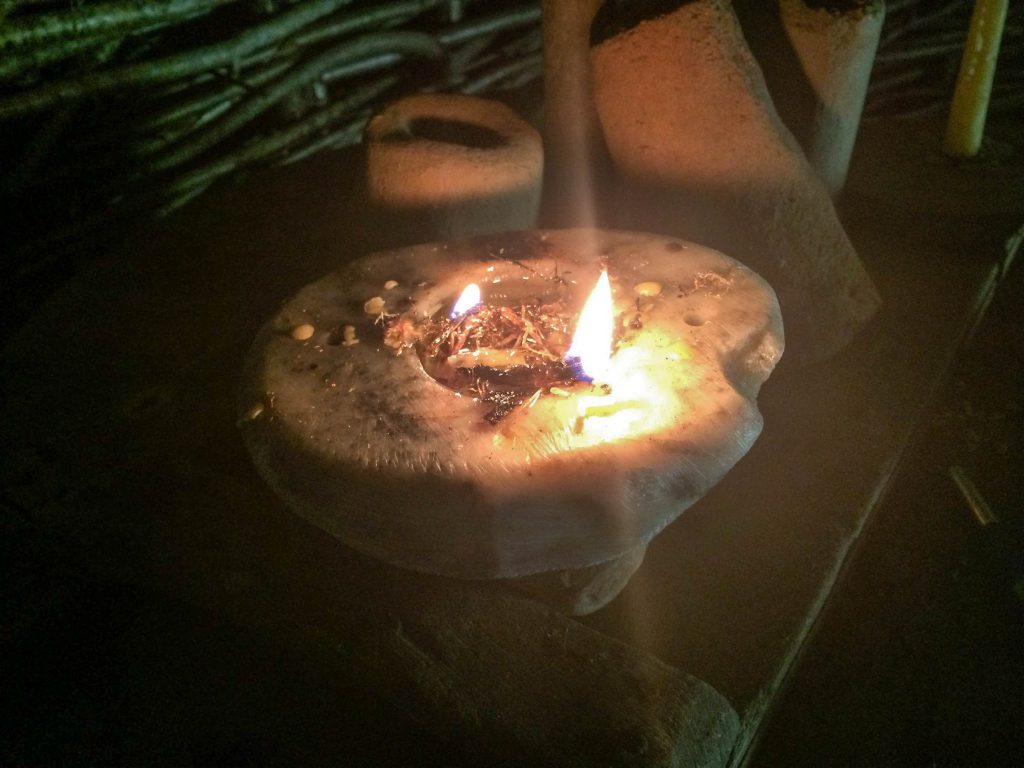

In ancient Mesoamerica, the Maya built their cities in the tropics during the Classic (A.D. 250–900) and Post Classic (A.D. 900–1521) periods. Nighttimes were busy: hunting, guarding the fields, preparing the next day’s meals, feasting, and celebrations all took place when people weren’t sleeping. As dusk set in and vision waned, other senses became heightened. Jaguars roamed the landscape and insects buzzed about, creating a profusion of sounds unique to the night. Tropical plants bloomed in the cool nighttime air, adding scents to the nocturnal ambience. Crackling fires in torches, hearths, and ceramic vessels illuminated and warmed the cool tropical nights and warded off beings, both real and fantastical, in the dark.

Night was both an ominous and sacred time. People made offerings to appease the gods who ruled the underworld, thereby ensuring the rising of the sun. The Moon Goddess rode her deer across the night sky, keeping watch over those who dared to venture into darkness. Sacred ceremonies took place in which royal persons imbibed hot, inebriating cacao drinks and danced at midnight. People across the social spectrum practiced bloodletting—drawing blood with obsidian blades, stingray spines, and thorn-lined ropes—in order to honor their ancestors. Astronomical readings of Venus determined whether war was on the horizon or if peace was prudent.

Likewise, in the urban area of Copan, Honduras, for some 250 years (A.D. 600–850) city dwellers shared a noisy nocturnal life in closely built housing. They slept on their stone benches, which were covered with cloth and padding for comfort. Others who lived outside of the city likely had portable sleeping mats, like those found from the incredibly well-preserved Classic farming community of Joya de Cerén, El Salvador. The Classic Maya wrote about many of these activities, and we are fortunate today to be able to understand their hieroglyphic writing, some of which gives us insight into their nightlife.

Night was both an ominous and sacred time.

In other areas of the world, people created lighting technologies that inform us about the relationships they perceived between the night, darkness, and death. Every day at dusk in ancient Egypt, the sun god Ra died in the west, casting the world into darkness. According to ancient Egyptians, the dead also traveled to the west—to Osiris, god of the underworld. Lighting played essential roles in funerary rituals during the dynasties of the New Kingdom period, which began in 1570 B.C. (nearly a thousand years after the Pyramids at Giza were built) and ended in 1069 B.C. “Wicks-on-sticks” are pictured on the famous Book of the Dead papyrus, and one of these lighting devices was discovered in King Tutankhamun’s tomb.

These are just a few of the nighttime practices that have taken place around the world over the course of history. In Oman, Bronze Age (3100–1300 B.C.) farmers irrigated their crops in the cool night air to reduce evaporation, and later, in Iron Age Zimbabwe (A.D. 200–1900), metalworkers fired up their forges at night to escape the blaze of the sun. Over 4,000 years ago in ancient Pakistan at the famous archaeological site of Mohenjo-daro, the removal of night soil (human excrement) was a task that was considered best suited to darkness, and in Polynesia, for centuries, ancient mariners looked to the stars to guide them on their long journeys home. The Vikings living in northern Europe during the Dark Ages used fish-oil, whale-fat, and seal-blubber lamps to light the dark interiors of their pithouses, and in 19th-century Bahamas, enslaved people achieved freedom, if only for a while, under cover of darkness.

Fast-forward to today, when the glow from cityscapes drowns out the stars and creates a brilliant night sky our ancestors would not recognize. As we’ve studied the archaeology of the night, we’ve become starkly aware of how much we are losing today by over-lighting the world.

Our modern nocturnal footprint is so bright that it is detected from outer space. We have “night mayors” in cities that never sleep, millions of people working night shifts, and health problems associated with the disappearing night as darkness gives way to the brightness of electrical illumination. Recent research demonstrates that circadian rhythms control 10–15 percent of our genes and that interruptions of these rhythms are linked to medical disorders such as heart disease, insomnia, and depression. Some researchers even suggest that certain cancers are likely caused by exposure to excessive nighttime lighting.

There are also social implications to our overlit lifestyles: For most of our past, people would gather around campfires at night to tell stories and sing songs, much like many Westerners do today on the rare occasions when we find time to go camping. With the advent of electric light, we don’t need to congregate in one place—we are free to follow more solitary pursuits, bathed in our individual sources of light.

On top of the health and social effects among humans, the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the dark environment of night, has brought to our attention the ecological damage we are causing to numerous species all over the world. There are many “poster animals” for the impacts of our harmful light pollution: Sea turtles and migrating birds stand out as those most endangered by humans’ nocturnal habits. Not to mention the fact that more lights require the burning of more fossil fuels and thus an increased contribution to climate change.

The IDA provides numerous ideas about how we can regain the dark, such as using dark-sky friendly outdoor lighting and advocating for lighting ordinances in local communities. Even in the brightest countries in the world, such as Japan, it’s possible to preserve an entire area, such as the certified International Dark Sky Place in the national park of the Yaeyama Islands. Each of us can do our part to lessen the brightness of modern nights.

Our archaeological inquiries into the night have taught us that while our relationships with the night have shifted, we remain part of the darkness, part of the night. It is essential to our well-being—and that of the planet—that we do what we can to turn out the lights.