What If Neanderthals Had Outlived Homo Sapiens?

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished with Creative Commons.

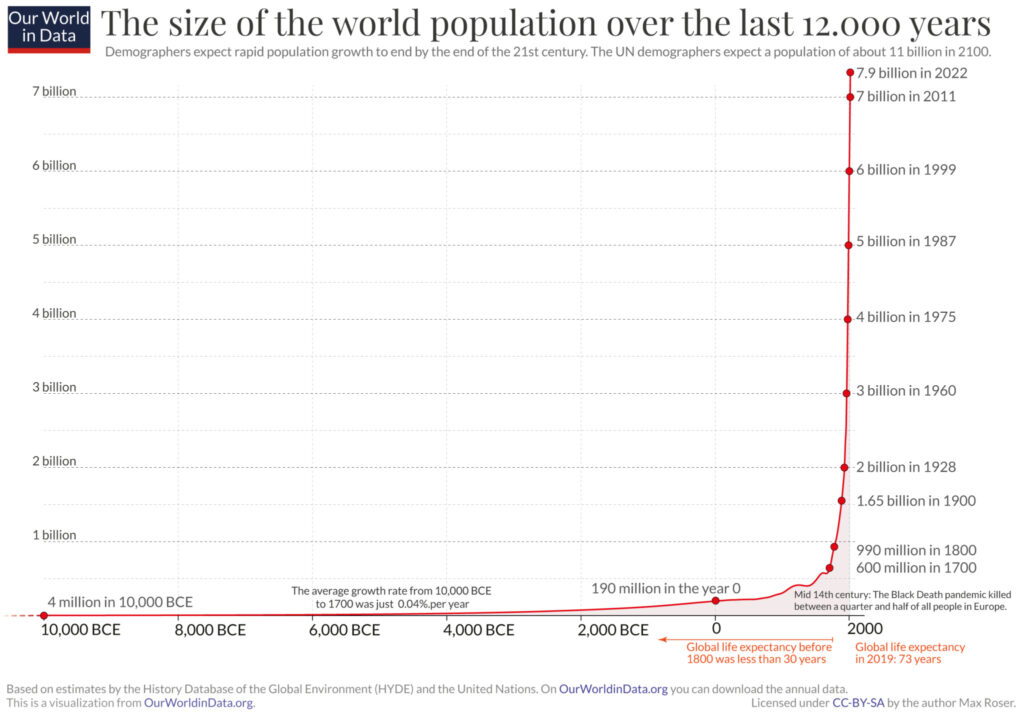

IN EVOLUTIONARY TERMS, the human population has rocketed in seconds. The news that it has now reached 8 billion seems inexplicable when you think about our history.

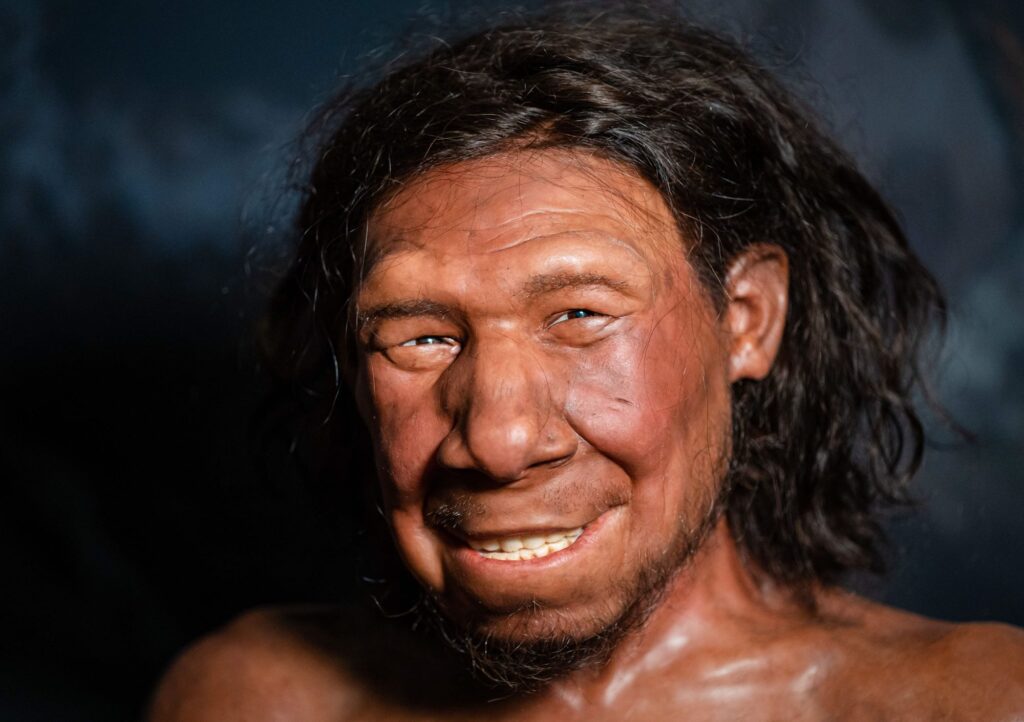

For 99 percent of the last million years of our existence, people rarely came across other humans. There were only around 10,000 Neanderthals living at any one time. Today there are around 800,000 people in the same space that was occupied by one Neanderthal. What’s more, since humans live in social groups, the next nearest Neanderthal group was probably well over 100 kilometers away. Finding a mate outside your own family was a challenge.

Neanderthals were more inclined to stay in their family groups and were warier of new people. If they had outcompeted our own species (Homo sapiens), the density of population would likely be far lower. It’s hard to imagine them building cities, for example, given that they were genetically disposed to being less friendly to those beyond their immediate family.

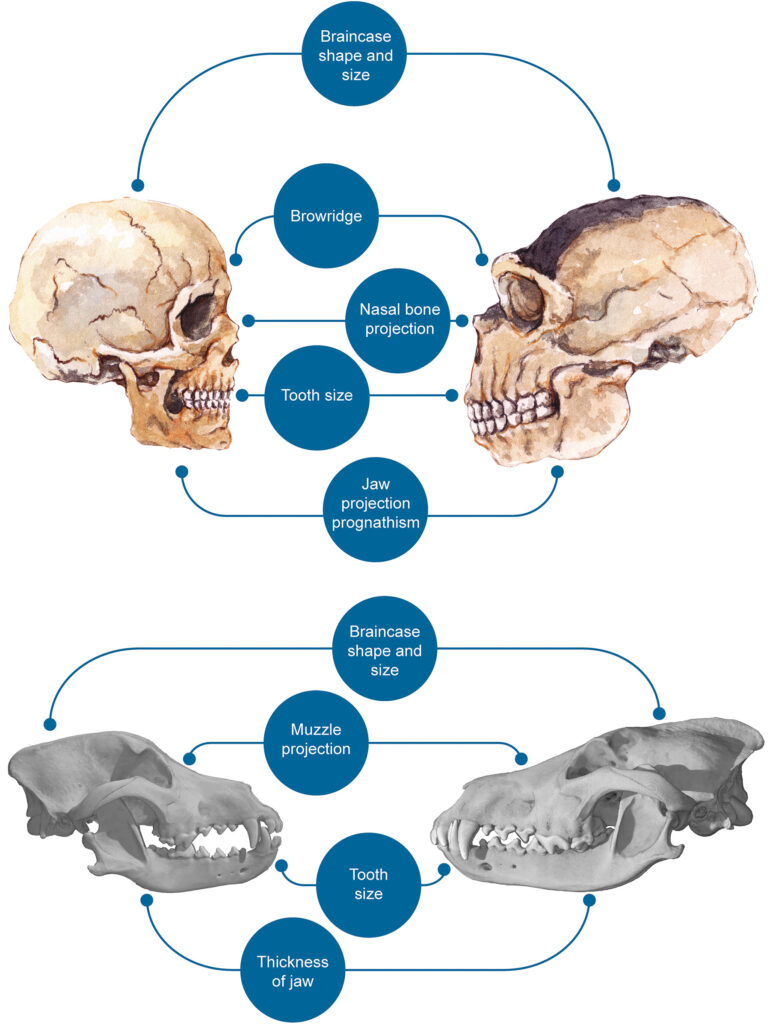

The reasons for our dramatic population growth may lie in the early days of H. sapiens more than 100,000 years ago. Genetic and anatomical differences between us and extinct species such as Neanderthals made us more similar to domesticated animal species. Large herds of cows, for example, can better tolerate the stress of living in a small space together than their wild ancestors who lived in small groups, spaced apart. These genetic differences changed our attitudes to people outside our own group. We became more tolerant.

As H. sapiens were more likely to interact with groups outside their family, they created a more diverse genetic pool, which reduced health problems. Neanderthals at El Sidrón in Spain showed 17 genetic deformities in only 13 people, for example. Such mutations were virtually nonexistent in later populations of our own species.

But larger populations also increase the spread of disease. Neanderthals might have typically lived shorter lives than modern humans, but their relative isolation will have protected them from the infectious diseases that sometimes wiped out whole populations of H. sapiens.

PUTTING MORE FOOD ON THE TABLE

Our species may also have had 10–20 percent faster rates of reproduction than earlier species of human. But having more babies only increases the population if there is enough food for them to eat.

Our genetic inclination for friendliness took shape around 200,000 years ago. From this time onward, there is archaeological evidence of the raw materials to make tools being moved around the landscape more widely.

From 100,000 years ago, we created networks along which new types of hunting weapons and jewelry such as shell beads could spread. Ideas were shared widely, and there were seasonal aggregations where H. sapiens got together for rituals and socializing. People had friends to depend on in different groups when they were short of food.

And we may have also needed more emotional contact and new types of relationship outside our human social worlds. In an alternative world where Neanderthals thrived, it may be less likely that humans would have nurtured relationships with animals through domestication.

DRAMATIC SHIFTS IN ENVIRONMENT

Things might also have been different had environments not generated so many sudden shortfalls, such as steep declines in plants and animals, on many occasions. If it wasn’t for these chance changes, Neanderthals may have survived.

Sharing resources and ideas between groups allowed people to live more efficiently off the land by distributing more effective technologies and giving one another food at times of crisis. This was probably one of the main reasons why our species thrived when the climate changed while others died. H. sapiens were better adapted to weather variable and risky conditions. This is partly because our species could depend on networks in times of crisis.

During the height of the last ice age around 20,000 years ago, temperatures across Europe were 8–10 degrees Celsius lower than today, with those in Germany being more like northern Siberia is now. Most of Northern Europe was covered in ice for six-to-nine months of the year.

Social connections provided the means by which inventions could spread between groups to help us adapt. These included spear throwers to make hunting more efficient, fine needles to make fitted clothing and keep people warmer, food storage, and hunting with domesticated wolves. As a result, more people survived nature’s wheel of fortune.

H. sapiens were generally careful not to overconsume resources like deer or fish, and were likely more aware of their life cycles than much earlier species of human might have been. For example, people in what is today British Columbia, Canada, only took males when they fished for salmon.

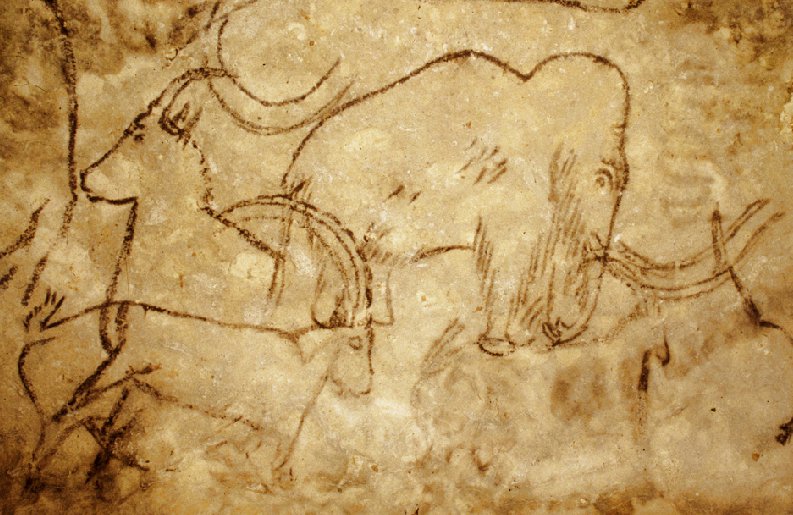

In some cases, however, these life cycles were hard to see. During the last ice age, animals such as mammoths, which roamed over huge territories invisible to human groups, went extinct. There are more than 100 depictions of mammoths at Rouffignac in France dating to the time of their disappearance, which suggests people grieved this loss. But it is more likely mammoths would have survived if it wasn’t for the rise of H. sapiens because there would have been fewer Neanderthals to hunt them.

TOO CLEVER FOR OUR OWN GOOD

Our liking for one another’s company and the way spending time together fosters our creativity was the making of our species. But it came at a price.

The more technology humankind develops, the more our use of it harms the planet. Intensive farming is draining our soils of nutrients, overfishing is wrecking the seas, and the greenhouse gases we release when we produce the products we now rely on are driving extreme weather. Overexploitation wasn’t inevitable, but our species was the first to do it.

We can hope that visual evidence of the destruction in our natural world will change our attitudes in time. We have changed quickly when we needed to throughout our history. There is, after all, no planet B. But if Neanderthals had survived instead of us, we would never have needed one.