Reconsidering Fragility in Museums—and the World

Over several months in 2022, climate activists engaged in a series of public protests in museums by throwing soup, mashed potatoes, and cake at paintings by Vincent Van Gogh, Claude Monet, and Leonardo da Vinci. In response, the International Council of Museums (ICOM) in Germany released a statement in November on behalf of a group of European museum directors. “The activists responsible for [the attacks],” they claim, “severely underestimate the fragility of these irreplaceable objects.”

When I read this, I laughed, and not kindly.

First, many of these paintings are under glass, some of it bulletproof. Second, as a conservator at the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA), I am well aware of the vulnerabilities of material heritage, as well as the energy, labor, and money required to maintain it. But even as a museum professional, the potential harm to famous artworks valued at tens of millions of dollars—some of which increased in value after they were targeted by climate activists—causes me no anxiety whatsoever.

I see evidence of far more pressing and destructive trends in the ethnographic collections with which I work. Many of these objects were taken by colonial researchers, are laced with pesticide residues, and were made from the skins, fur, and feathers of animals that are now extinct or threatened in their native regions. The museum objects themselves often reveal the fragility of irreplaceable human cultures due to colonialism and the fragility of nature caused by unsustainable processes of extraction.

Museum directors and advocates have underestimated these institutions’ historic and current contributions to unsustainable systems. I believe climate activists are well aware of museums’ problematic practices.

In light of these protests, it is time for museum administrators and supporters to reflect on the damage that has been done to natural and cultural resources by building and maintaining these collections. Museums and the public must engage in a larger conversation about preserving fragile heritage—and repairing humanity’s relationships with both natural resources and one another.

One recent day, as on many others, I find myself working with a fragile object. In this case, it’s a small pig figurine—a Day of the Dead offering from Mexico. Considering it is more than 100 years old and made only of pressed sugar and gold foil, it’s in surprisingly good condition.

This sugar pig is typical of the vulnerable materials I encounter every day. As a conservator, I have been trained to document and preserve material heritage like this, to keep it safe and in one piece. As a specialist in archaeological and anthropological collections, I work with a broad diversity of objects, including textiles, stone tools, musical instruments, furniture, weapons, and, occasionally, food.

As I look at the little pig, I wonder what the collector was thinking when they brought this object to Cambridge. How long was this candy animal meant to survive here? How was it meant to transmit knowledge in this context?

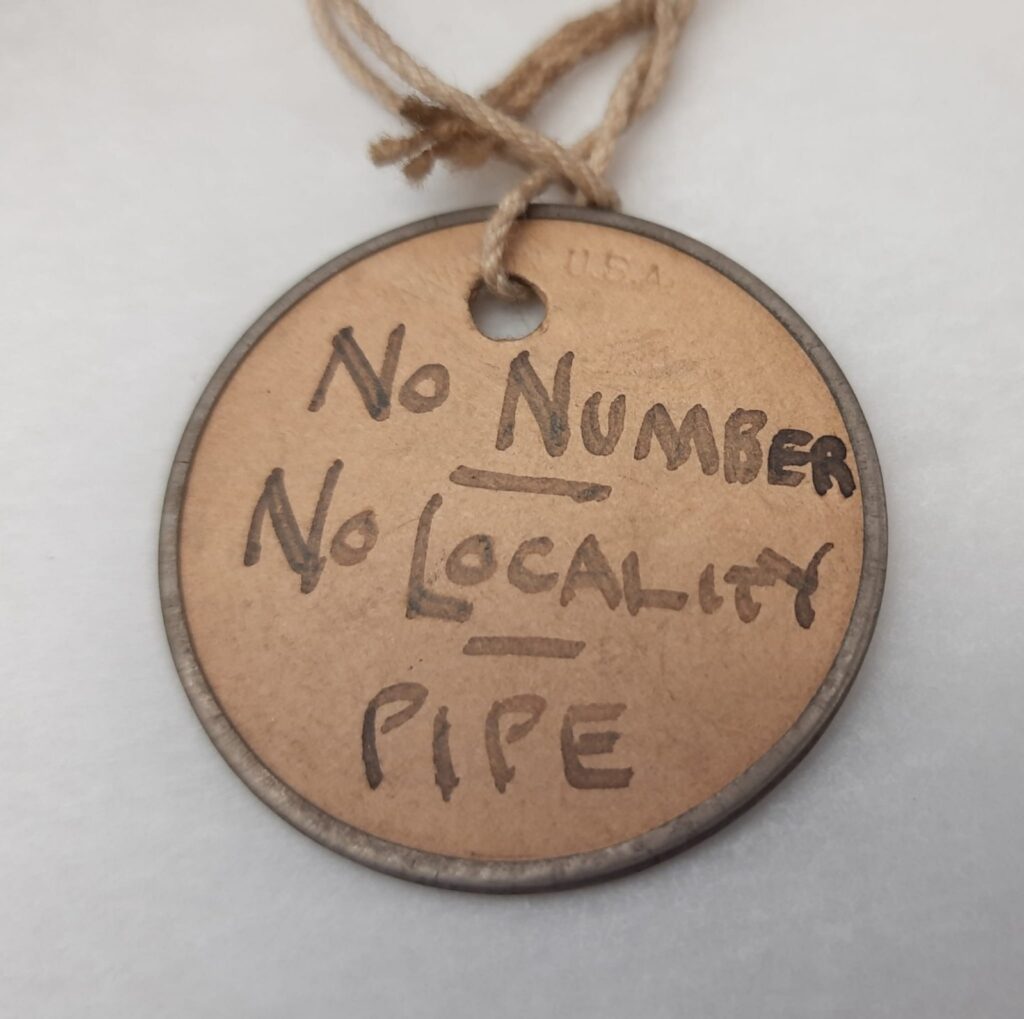

Sadly, I don’t always have access to this information. The collection at MAA represents the work of many people and intentions accumulated over more than a century. It is not uncommon for details about the original function of objects to be lost, destroyed, or inaccurate. In one instance, I wrote to a specialist in the human uses of birds about what had been described in our records as an Amazonian headdress. He replied that, based on the feathers used, it was likely from Papua New Guinea.

Unlike oil paintings or marble sculptures—the types of objects often found in European fine arts museums—the materials in ethnography collections are complex and highly varied. They are also relatively sensitive to problems common to museum storage, including pest infestations, neglect, and seasonal fluctuations in temperature and humidity that can cause mold and deformation. Fragile materials like plant fibers and fur need frequent monitoring to prevent these problems.

In any museum, keeping collections “alive,” as it were, can require a staggering amount of infrastructure, including the maintenance of multiple storage facilities, data management and security systems, educational programs, and a roster of volunteers. But in many cases, that’s still not enough.

It is not uncommon for a single member of a museum staff to be responsible for hundreds of thousands of objects from diverse cultural groups. Benign neglect—a lack of preventive care—is one of the most common problems in ethnographic collections. This pattern of deterioration is often exacerbated by keeping a large amount of material in storage and offering limited access to it.

Time and space are precious resources in museums. Nevertheless, these institutions are constantly growing. The expansion of ethnographic collections in particular over the past 150 years has far outpaced these museums’ capacity to care for their materials responsibly and consistently.

Museum administrators are increasingly aware that our current recommended standards and practices are unsustainable, particularly when it comes to climate change issues such as energy use and waste management. Some institutions are making improvements, such as incorporating eco-friendly design into their buildings and raising awareness about biodiversity loss through their exhibits.

Yet, as the ICOM response to climate protestors indicates, institutions are far from accepting criticism about what they perceive to be their fundamental function: physically protecting material heritage above any other consideration.

I believe museum professionals must examine the flaws in our collecting and preservation practices. And we must reckon with our role in creating and perpetuating a problematic system of consumption of the world’s natural and cultural resources.

A recent exhibition at MAA featured a Hawaiian cloak, or ‘ahu‘ula, made with feathers from the ‘ō‘ō, a bird whose genus is now extinct due to overhunting and habitat encroachment. To make the cloak, one or more craftspeople had tied tens of thousands of feathers in small bundles to a grid-like network of knotted plant fiber. Based on the cumulative effort and design, it is clear these materials had social value and utility to local communities.

The collection at MAA includes many objects made from threatened species: shields crafted from rhinoceros hide, pangolin scales used for medicine, coral jewelry, and the skins of several species of large cat worn in demonstrations of status. The depletion of animals from the world’s ecosystems over the past two centuries is uniquely tangible to me as these objects cross my work bench. So is the role a culture of collection and extraction has played in their depletion.

All over the world, colonial scholars produced histories, accounts, and travelogues that fueled a global demand for these objects. Animals, plants, and other materials were unsustainably exported as personal or cultural properties, many of which ended up in museums. At times, colonial collectors acquired cultural heritage through unethical means or theft.

This system of collection and extraction contributed to the foundations of the modern museum as an institution for the acquisition, storage, preservation, and display of material heritage. Some museums continue to benefit from this system by showcasing these objects; others are confronting their cultural and environmental legacy.

Conservators recognize that removing material heritage from the context in which it has been historically produced, maintained, or activated is itself an agent of deterioration, like strong light or a natural disaster. Yet this type of damage is often where my training is least useful because I am ignorant of the cultural systems, narratives, and values through which the original communities historically maintained these objects.

Many anthropology museums and natural history collections did further damage by applying chemical pesticides to cultural heritage. Though these contaminants have arguably extended the lives of skins, textiles, and feathers vulnerable to insect attacks, they often prevent ethnographic collections from being used as teaching tools. These toxic substances are also detrimental to the health of the environment and museum staff.

Furthermore, this pesticide use is poorly documented. Especially in cases of repatriation, it is essential that museums are transparent about the legacy of pesticide use in order to inform local custodians about safe handling and to repair damaged relationships between objects, people, and traditions of care.

Thankfully, not every object tells a story of deterioration. Elsewhere in the MAA collection, I have found evidence of highly skilled techniques for repair and innovation that have been perfected outside the museum context. Cracked gourd containers are lovingly reinforced with cord. Industrial metals that arrived through trade have been reused as decorative elements. Ceremonial garments are patched several times over. And prayer wheels are fashioned from upcycled vegetable tins.

These creative solutions for resource management force me to question whether a museum storage facility, and my expertise as a conservator, represent the best possible setting for the long-term care of these objects. Is it possible they are better served by a more dynamic form of preservation than being placed in a box at a closed storage facility? How can museums think outside the box—literally and figuratively—to reimagine how and why we value these collections?

I have been asked many times about the oldest or most expensive thing I’ve ever worked on, but never the most fragile. I often respond with an analogy to wildlife conservation since neither of our professions is particularly interested in property value. When I think about the preservation of cultural heritage, what makes me anxious is not gemstones, statues, or expensive paintings under glass. It’s the Hawaiian ‘ahu‘ula, with its irreplaceable feathers from an extinct bird, crafted through an interrupted cultural tradition.

The fragility of material heritage is therefore much more complex than the ICOM statement seems to suggest. As the deteriorating condition of objects in ethnographic museums indicates, displacement and damage are potentially inherent to a system marked by broken relationships among groups of people and deteriorated connections between humans and nature. The instability of these collections results from the ways many modern museums and the societies that support them have chosen to value, extract, and preserve natural and cultural resources.

I believe climate activists recognize the unsustainability of a system that accumulates and protects cultural heritage as material wealth. I see their concerns reflected in the spears, parkas, and fish traps I handle at work.

For better or worse, ethnographic collections have the capacity to remind us of a crucial point at this time in our history: Humanity’s survival depends on our ability to respect the natural world and make its care part of our heritage.