Broken Bones Could Rewrite Story of the First Americans

In the fall of 1992, a construction crew made an unusual discovery during a freeway expansion in a coastal area of San Diego County. Buried deep within the silty soil were the bones, tusks, and molars of a mastodon, an elephant-like mammal that once lived in North America. When archaeologists took a closer look, they found signs that humans had battered the animal shortly after its death with the large stones buried alongside it.

But the real surprise came when geologists determined the age of the bones. Radiometric dates showed the mastodon had been buried for about 130,000 years. If correct, this means that ancient humans were in coastal California many tens of thousands of years before they were thought to be in the Americas. The details of the finding, which took 25 years to unravel, were published in Nature today, raising questions about when humans first migrated to North America.

“It’s a huge claim,” says John McNabb, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom, who was not part of the study. “It’s 115,000 years older than most people would accept as the earliest occupation of the Americas.”

Most archaeologists generally agree that humans traveled into North America about 14,500 years ago and then spread across the continent. The Clovis people, once thought to be the first humans to enter the Americas, lived about 11,000 years ago, but the recent discoveries of ancient feces in Oregon, the remains of a large campsite in southern Chile, and bones and stone tools at the bottom of a Florida river have bumped the timeline at least 2,000 years earlier. Other studies have heated the debate, placing humans in the Calico Hills in California 50,000 to 80,000 years ago, in Brazil 20,000 to 40,000 years ago, and in Canada’s Yukon Territory as early as 24,000 years ago.

Perhaps it’s not surprising then that many are skeptical about the new claims. “If you are going to push human antiquity in the New World back more than 100,000 years in one fell swoop, you’ll have to do so with a far better archaeological case than this one,” says David Meltzer, who studies the origins of the first Americans at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Texas.

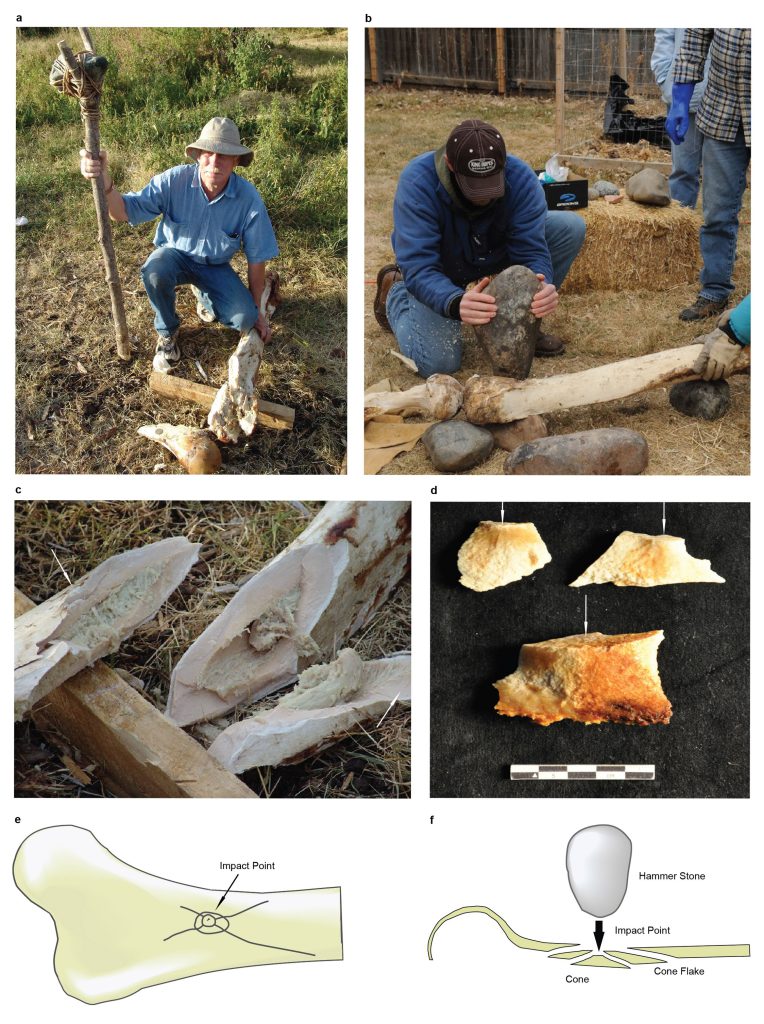

According to the analysis in Nature, the position of the bones, the clusters of stones nearby, and the fracture patterns on the bones all point to someone bludgeoning the mastodon—perhaps for food or to use the bones as tools. The radiating spiral fractures, the cone-shaped bone flakes, and the notches in the bones could only have been made by humans, says Steven Holen, an expert in early human archaeology and bone technology at the Center for American Paleolithic Research, who worked on the study. As part of the investigation, the team broke elephant and cow bones using stone or wood anvils and heavy stone hammers to compare the breakage patterns.

What’s more, the authors claim, the fossils were found in fine-grained sediments, making it unlikely that a storm or landslide had deposited the rocks next to the mastodon. Finally, geologists used a technique called uranium-thorium radioisotope dating to put the age of the bones at 121,000 to 140,000 years old.

Despite the detailed study and the authors’ attempts to exclude all natural explanations for the patterns they found, many experts remain unconvinced. Meltzer and others say it doesn’t show that people were the only force that could have fractured the bones and modified the stones. McNabb points to the lack of corroborating tools, such as well-made stone tools like flakes or scrapers, which are typically found at butchery sites of the same age or older. Luis Borrero, an archaeologist in Argentina who studies first peopling sites, wants to know about any information that “does not fit within their interpretation.”

For its part, the team has invited other researchers to take a look at the artifacts. They also intend to reconsider broken limb bones in collections across Southern California and re-examine the material collected from other sites. In the past, paleontologists and archaeologists may not have been looking for the right clues in the right places, says Holen. “A lot of the evidence may have fallen between the academic cracks of archaeology and paleontology.”