Imagining the Neanderthal’s World

Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death, and Art by Rebecca Wragg Sykes. Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020.

Archaeology and genomics keep enriching and complicating the story of human lineage. Homo sapiens had more (and closer) company than we once suspected, including relatives such as the Denisovans, the hobbit-like Homo floresiensis, and Homo luzonensis, from the Philippines. New research also has upended our views of Neanderthals.

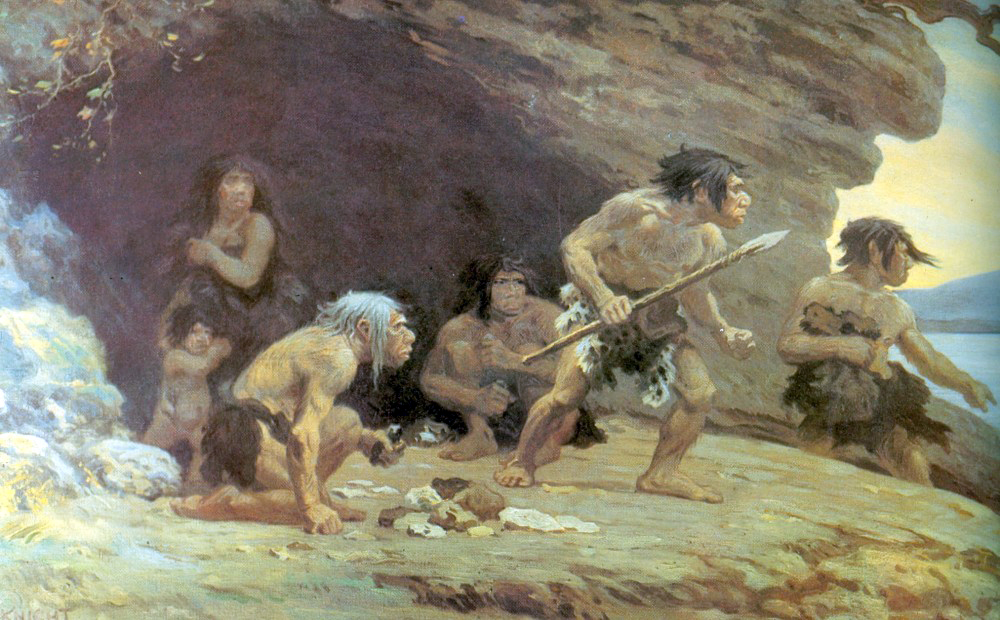

We once thought we knew Homo neanderthalensis. We imagined cave men and women with squat muscular physiques and protruding brows, chilled by the Ice Age, outcompeted or vanquished by modern humans, and rendered extinct approximately 40,000 years ago. But much of this received wisdom has turned out to be questionable or false.

Discoveries over the last decade or so have narrowed the distance, intellectual and otherwise, between Neanderthals and modern humans. Alongside fossilized bones and stone tools, we now have evidence of symbolic architecture, personal adornment, cave art—and, perhaps most intriguing, the persistence of Neanderthal DNA in our own genome.

Rebecca Wragg Sykes’ Kindred: Neanderthal Life, Love, Death, and Art is part of this revisionist reckoning. It joins other recent titles in advancing the still-controversial case that Neanderthals were more cognitively complex than the old cave man conceptions suggest. In The Smart Neanderthal, for example, the evolutionary biologist Clive Finlayson attacks what he calls “the paradigm of Neanderthal inferiority.” Relying in part on evidence that Neanderthals caught birds, ate them, and used their feathers for adornment, he insists that they were, in fact, “our cognitive equals.”

Passionately pro-Neanderthal, Wragg Sykes sums up the case for their relative sophistication on the basis of considerable evidence from archaeology and related disciplines. In titling her book Kindred, she underlines that Neanderthals are kin to us, worthy of not just reconsideration but respect.

An archaeologist and science writer, Wragg Sykes hasn’t left her academic training behind—the source of her book’s weaknesses, as well as its strengths. She knows the field, in all its burgeoning complexity. In thumbnailing her conclusions, she can write clearly and persuasively. But too often she is too close her subject, lapsing into arcane detail, losing readers in a welter of jargon.

Wragg Sykes nevertheless aspires, in fits and starts, to narrative eloquence. She begins each chapter with an imagistic prologue—more purple prose than prose poetry. These italicized passages are speculative, highly romantic reconstructions of the lost world of the Neanderthals. Here, for example, is her valedictory for the imaginary last Neanderthal in Iberia:

“At the end of the world, literally and figuratively, the last Neanderthal in Iberia witnesses a low, glinting sun across the distant Mediterranean. As a flint-dark sky lightens to grey dawn, soft coos of rock doves clash with the keening of lost gulls, crying like hungry children. But there are no more babies, no more of the people left, no one at all to join in watching the stars disappear; to hold vigil until the last breath leaves the air to cool.”

There’s (too) much more of this, unintegrated with the narrative that follows, which mingles excursions into archaeological history with contemporary analysis. But, if nothing else, these flights of fancy show just how powerfully Neanderthals inhabit Wragg Sykes’ imagination.

Wragg Sykes’ main mission is to burnish the Neanderthal brand. “Neanderthals matter; have always mattered. They possess pop-cultural cachet like no other extinct human species. Among our ancient relatives (known as hominins), Neanderthals are truly A-list,” she writes. They were not, she insists, “dullard losers on a withered branch of the family tree, but enormously adaptable and even successful ancient relatives.”

Wragg Sykes also highlights the increasing sophistication of archaeological and genetic techniques, with “insights … as likely to emerge under the lens of a microscope as at the edge of a trowel.” Complementing discoveries in the field, new methods allow for the reconsideration—and reinterpretation—of old evidence. The result, astonishing at times, resembles virtual time travel, as researchers hone remarkable (if still disputed) theories about Neanderthal customs and cognition from the charred remains of a hearth, a butchered animal carcass, or a hand-colored shell.

In assessing Neanderthals, Wragg Sykes underlines just how ubiquitous they were over their 350,000-year existence. They flourished in a variety of climates and terrains across present-day Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, occupying not just the glaciated tundra of our modern myths, but forests, deserts, coasts, and mountains.

This latter point partially rebuts the notion that Neanderthals had trouble adapting to climatic change. In fact, Wragg Sykes argues, they were hugely versatile, including in their culinary habits. They were able to hunt large mammals, such as mammoths, but also small ones. They trapped birds, caught fish and other seafood, “gorged on tortoises,” and ate vegetables too.

Based on the (limited) archaeological evidence, Wragg Sykes suggests that Neanderthals may actually have been less violent than H. sapiens. She sees even “butchery and cannibalism as acts of intimacy, not violation,” less about nutrition than about processing grief. In this area, as in others, she affords Neanderthals the benefit of the doubt.

Wragg Sykes spends considerable time discussing the technology of stone tools, or lithics, describing Neanderthals as skilled artisans. “The overarching story,” she writes, “has been that Neanderthals used stone in more systematic, complicated, and nuanced ways than was ever suspected,” showing them to be “hominins at the top of their game.”

The most intriguing space Neanderthals left may be a cavern in southwest France with rings of broken, charred stalagmites.

Recent, rarer finds show that Neanderthals also worked with shell, bone, and wood, with which they fashioned finely crafted spears. “While minds create things, things also create minds,” Wragg Sykes writes, hypothesizing that making composite tools “must have reinforced concepts of connectedness and collaboration.”

Neanderthals, though presumably nomadic, also designed homes, creating what Wragg Sykes calls “complex, intentional divisions of space.” The most intriguing space they left behind may be a cavern near Bruniquel, in southwest France, with rings of broken columns of charred stalagmites. Wragg Sykes links that construction, about 174,000 years old, to the possibility of spoken communication. “They certainly laughed, probably joked, and may have memorized chronicles,” she writes, taking a cognitive leap of her own. (Whether Neanderthals could even speak remains a matter of debate.)

Wragg Sykes also makes the case for Neanderthal cave art, citing three Iberian caves with hand stencils and other markings that predate H. sapiens presence in the area. Elsewhere in Europe, she notes, patterned bone engravings have been found. Such evidence, she says, is “increasingly leading even sceptics to accept that Neanderthals had an aesthetic, symbolic element to their lives.”

In her enthusiasm, Wragg Sykes goes further than some experts. In The Accidental Homo Sapiens, for example, paleoanthropologist Ian Tattersall and entomologist Rob DeSalle argue that while Neanderthals were “highly skilled and intelligent,” the record does not show them “regularly thinking in a symbolic manner.”

Recent genetic studies have convinced Wragg Sykes, along with other scholars, that considerable interbreeding occurred between Neanderthals and H. sapiens. Her conclusion is that “the ‘end’ of the Neanderthals was a process involving bodily and probably cultural assimilation.” She also insists that “long-standing claims that early H. sapiens possessed some intrinsic superiority are far from tenable.”

Kindred, Wragg Sykes writes, is “for those who’ve heard of the Neanderthals or not; for the vaguely interested to the amateur expert; even for the scientists lucky enough to research their ancient world.” Appealing to such diverse audiences—trying, metaphorically speaking, to describe both the forests and the trees—may constitute too ambitious a task. But Wragg Sykes makes at least one irrefutable point: We retain an enduring fascination with Neanderthals, an artifact of our obsession with the question of what it means to be human.