Forensic Methods Unveil Clues About Megafauna Extinctions

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

THE EARLIEST PEOPLE who lived in North America shared the landscape with huge animals. On any day, these hunter-gatherers might encounter a giant, snarling saber-toothed cat ready to pounce or a group of elephantlike mammoths stripping tree branches. Maybe a herd of giant bison would stampede past.

Obviously, you can’t see any of these ice age megafauna now. They’ve all been extinct for about 12,800 years. Mammoths; mastodons; huge bison, horses, and camels; very large ground sloths; and giant short-faced bears all died out as the huge continental ice sheets disappeared at the end of the ice age. What happened to them?

Scientists have pointed to various potential causes for the extinctions. Some suggest environmental changes happened faster than the animals could adapt to them. Others posit a catastrophic impact of a fragmented comet. Maybe it was overhunting on the part of humans or some combination of all these factors.

One of my major interests as an archaeologist has been to understand how the earliest Paleoindians lived and interacted with megafauna species. Just how implicated should humans be in the extinction of these ice age animals? In a new study, my colleagues and I used a forensic technique more commonly used to identify blood on objects at crime scenes to investigate this question.

TESTING STONE TOOLS LIKE MURDER WEAPONS

Archaeologists have uncovered a sparse scattering of stone tools left at the campsites of Paleoindian Clovis hunter-gatherers who lived around the time of the megafauna extinctions.

These include iconic Clovis spearpoints with their distinctive flutes: concave areas left behind by removed stone flakes that extend from the base to the middle of the point. People most likely made the points this way so they could easily affix them to a spear shaft.

Based on sites excavated in the western U.S., archaeologists know Paleoindian Clovis hunter-gatherers who lived around the time of the extinctions at least occasionally killed or scavenged ice age megafauna, such as mammoths. There they’ve found preserved bones of megafauna together with the stone tools used for killing and butchering these animals. These sites are crucial for understanding the possible role that early Paleoindians played in the extinction event.

Unfortunately, many areas in the southeastern U.S. lack sites with preserved bone and associated stone tools that might indicate whether megafauna were hunted there by Clovis or other Paleoindian cultures. Without evidence of preserved bones of megafauna, archaeologists have to find other ways to examine this question.

Forensic scientists have used an immunological blood residue analysis technique called immunoelectrophoresis for over 50 years to identify blood residue sticking to objects found at crime scenes. In recent years, researchers have applied this method to identify animal blood proteins preserved within ancient stone tools. They compare aspects of the ancient blood with blood antigens derived from modern relatives of extinct animals.

Residue analysis does not rely on the presence of nuclear DNA but rather on preserved, identifiable proteins that sometimes survive within the microscopic fractures and flaws of stone tools created during their manufacture and use. Typically, only a small percentage of artifacts produce positive blood residue results, indicating a match between the ancient residue and antiserum molecules from modern animals.

A previous blood residue study of a small number of Paleoindian artifacts in what are today South Carolina and Georgia failed to provide evidence that these people had hunted or scavenged extinct megafauna. The researchers found evidence of bison and other animals, such as deer, bear, and rabbit, but no evidence of extinct species of the Proboscidea order, such as mammoth or mastodon, or of an extinct species of North American horse (of the Equidae family).

IDENTIFYING ANCIENT PREY OF HUMAN HUNTERS

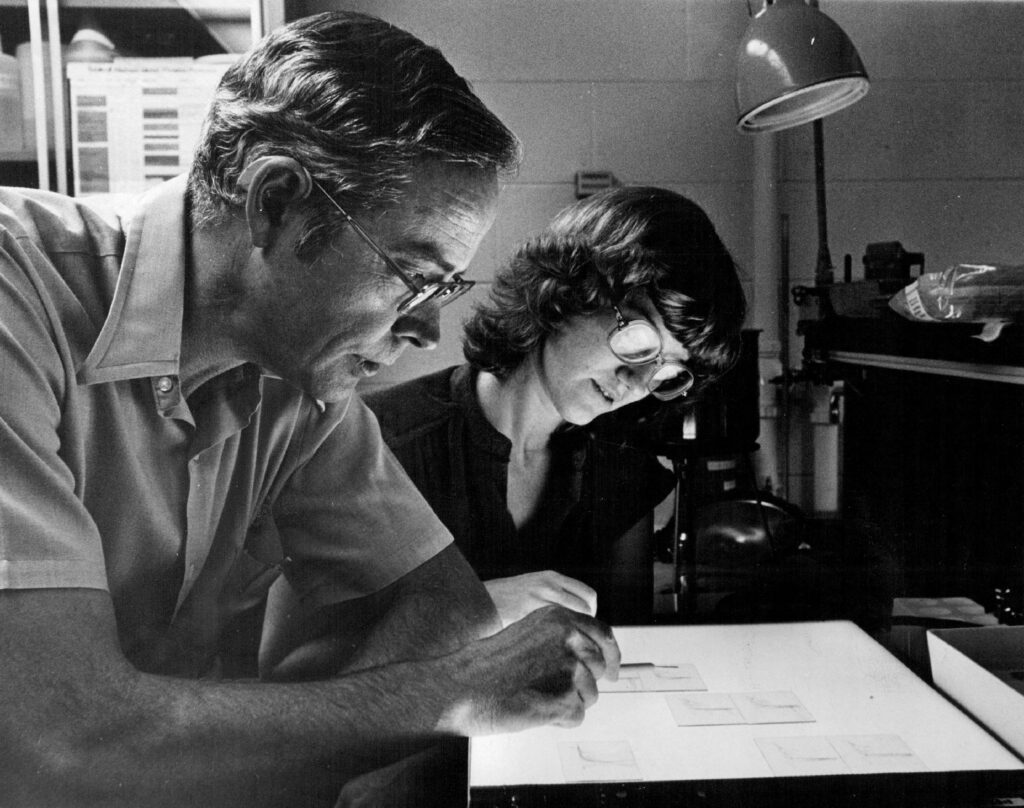

My colleagues and I realized we needed a much larger sample of Paleoindian stone tools for testing. Since Clovis points and other Paleoindian artifacts are rare, I relied heavily on local museums, private collectors, collections housed at state universities, and even military installations to amass a sample of 120 Paleoindian stone tools from all over North Carolina and South Carolina.

Because these artifacts are irreplaceable, I personally carried all 120 Clovis spearpoints and tools inside a protective case on a flight from South Carolina to the blood residue lab in Portland, Oregon. I coordinated in advance with the Transportation Security Administration so my collection of 13,000-year-old weaponry would make it through the screening process.

The blood residue analysis provided unambiguous proof that the tools had had contact with ancient animal blood proteins. The results included the first direct evidence on ancient stone tools of the blood of extinct mammoth or mastodon and the extinct North American horse on Paleoindian artifacts in eastern North America. This evidence is significant because it proves that these animals were present in the Carolinas and that they were hunted or scavenged by early Paleoindians.

In addition to extinct mammoth, mastodon, and horse, ancient bison (of the Bovidae family) blood residues were the most common, adding to earlier blood residue research suggesting a focus on bison hunting by Clovis and other Paleoindian cultures. Bison in North America did not go extinct but instead became smaller, most likely as a result of climate change as the last ice age ended and the climate warmed.

So what do these results suggest for the extinction debate? While this study does not prove humans were responsible for the extinctions, it does show that early Paleoindians across the continent likely hunted or scavenged these animals, at least occasionally. The results also indicate that ancient mammoths, mastodons, and horses were around when Clovis people were here—only a few hundred years before these animals’ eventual extinction in North America.

Another interesting finding is that while mammoth or mastodon blood residues are found on Clovis artifacts, blood residues for ancient horses are found not only on Clovis points but also on Paleoindian points that are slightly more recent than Clovis points. This may suggest the extinctions of mammoths and mastodons were complete in this region by the end of the Clovis period, and the extinction of ice age horse species took longer.

Testing an even larger sample of Paleoindian stone tools from different regions of North America could help pin down the timing and geographic variability in the extinction of megafauna species and provide more clues about why these animals disappeared when they did.