The Untold Stories of Archaeology’s Women

For Women’s History Month, it has become traditional to rifle through the great names of the past, pluck out a few that strike the imagination and have the appropriate gender marker, and dust them off for a new audience. We should know—we run the TrowelBlazers project, a largely community-sourced archive of biographies of women in the “digging” sciences: archaeology, geology, and palaeontology.

We absolutely delight in the stories of great women like Jane Dieulafoy, a sharpshooting cross-dresser of the late 1800s who once, having landed on the wrong side of a river while rafting, brandished her two trusty revolvers with their 14 bullets at a gang of eight armed assailants—and told them to come back when they had six more men.

We love the chutzpah of Margaret Murray, who at the turn of the 20th century taught hieroglyphics to everyone who was anyone and even had a sideline in the popular public spectacle of unwrapping mummies. She used her extensive research into pagan ritual to jokingly cast a hex on Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II that, she sometimes bragged, won the First World War for the Allies.

If you want to know about adventuresses, aviatrices, scuba pioneers, and gin drinkers, well, we have a site full of them.

What we don’t have (yet) is a site that reflects the full diversity of female experience. Since our founding in 2013, at times we have barely had a site at all because our effort (by four women with two jobs and a total of seven kids) to commemorate female achievement is unfunded, grassroots, and done between personal and professional demands that leave little time for riding hobbyhorses like the history of women in the “digging” sciences.

After several years of acquiring biographies of TrowelBlazing women that we, our friends, and our followers had heard of, we began to realize that a very particular kind of woman was dominating the stories. The typical TrowelBlazer was Anglophone, White, and upper middle-class, and had picked up a trowel for fun, not as a way to earn a living.

For every Margaret Murray slogging it out with low wages—when University College London (UCL) finally deigned to award her an honorary doctorate in 1927, her students chipped in to buy her a graduation robe—there were dozens of socially privileged, higher-profile women such as Hilda Petrie, Amelia Edwards, Gertrude Bell, or (not just murder mystery author) Agatha Christie, who never had to make digging pay. Their stories were easy to find because they were already the sort of people history cares about.

And therein lies the problem.

To make it as a TrowelBlazer when we first started this project, you had to know the right people. Take, for instance, Dame Kathleen Kenyon, the denim-wearing excavator of Jericho and sometime deputy head of the very Institute of Archaeology that never did pay Margaret Murray fairly. Kenyon—whose father ran the British Museum—got her first taste of archaeology back in 1929 on the recommendation of a teacher who knew the right people, signing on as a photographer (and a car mechanic) with Gertrude Caton-Thompson for her Great Zimbabwe dig.

Caton-Thompson was also how paleoanthropologist Mary Leakey got her start, when Caton-Thompson hired her as an illustrator. That was before Leakey’s famous 1959 discovery of “Zinj,” a species of hominin now called Australopithecus boisei. And it was Caton-Thompson’s good friend Dorothy Garrod who in 1939 became the first female professor at Cambridge and who ran the all-female excavation team at Mount Carmel that discovered the important Tabun Neanderthal fossils.

All these women, while absent from many textbooks, were easy for us to find. Kenyon was still a living legend at UCL, where some of us trained, having terrified the more nervous type of student for decades while storming down the corridors with her incorrigible canine companions. The Leakey family is world famous, and their paleoanthropological dynasty is now in its third generation. There are archives, records, photographs, journals, publications, monographs, and even poems about these women and their achievements. There are plaques in institutions of higher education, bursaries, and awards in their names now as more and more of their stories come to light.

We celebrate these women. They are worth celebrating. Like Hollywood star Ginger Rogers, they were doing everything that men were doing—just “backward … and in high heels” (metaphorically; sensible boots seem to have been the order of the day for most TrowelBlazing women). But we also need to be aware of the holes and gaps in our narratives.

Garrod and her excavation at Mount Carmel are now well-known, but until we read the work of dedicated researchers Pamela Jane Smith and Jane Callander, we unthinkingly gave her credit for the discovery of the important Neanderthal fossil Tabun 1.

It took their obsessive reading of Garrod’s own field notes to uncover the full story: Tabun 1 was identified from a single tooth pulled out of a sieve by the practiced hands of a local Palestinian village woman, Yusra, who was pregnant and earning cash working for the posh ladies in the tents. Yusra never made it to Garrod’s Cambridge college, or any college at all it seems, though she wanted to. She certainly never had buildings and whatnot named after her. The Smithsonian Institution, where Tabun 1 is housed, now credits Yusra for the find.

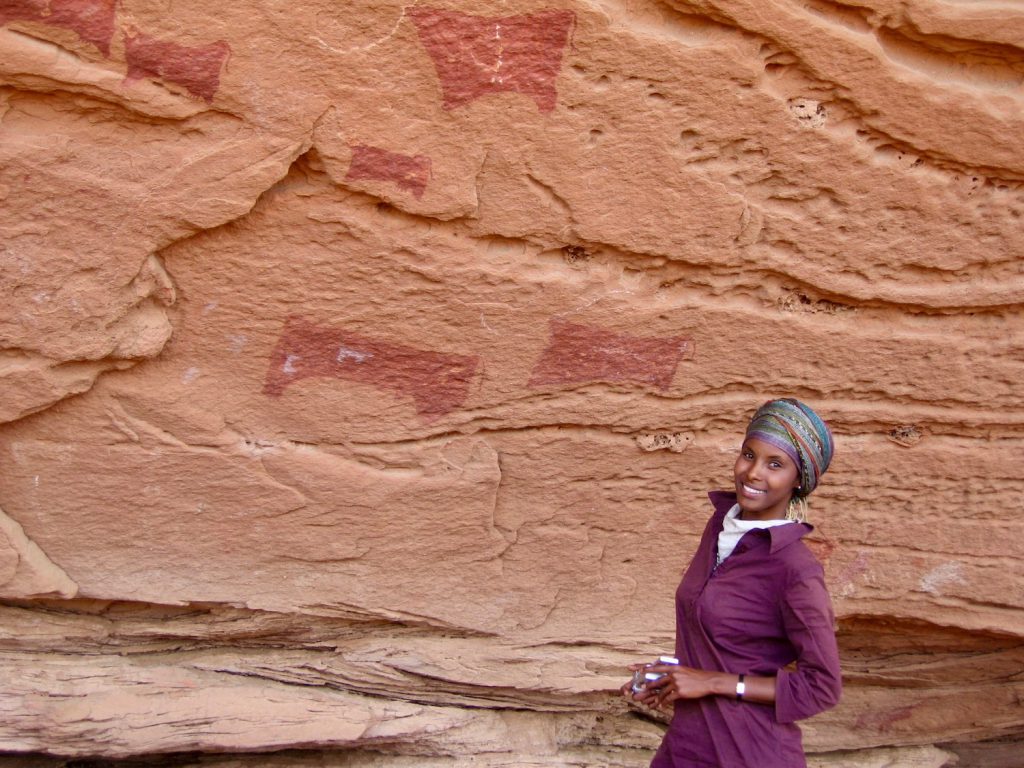

And what about the women who worked with Mary Leakey: Is the name Emma Mbua known worldwide, for example? Or, indeed, that of modern-day fossil-finders such as South Africa’s Zandile Ndaba? What about pioneering Swedish-Somali archaeologist Sada Mire or the up-and-coming archaeologists like Ivorian Aïcha Gninin Touré?

It is possible to change how history is written to include people on the margins and in the marginalia.

That is the point we wish to make in this month where we celebrate women’s history: Even the best-intentioned efforts are very often celebrating only one kind of woman, with one kind of history. By skimming history, we end up with an archive of female achievement that reflects the women whose stories it is easiest to find—because they were already networked into the institutions that still shape careers today.

Last year, during the pandemic, we had a little experiment in “digital fieldwork” at TrowelBlazers. We asked a group of students to critically examine our archives, then to follow their own interests and instincts to create new biographies. They came back with new entries that were a sheer joy to add to the site—diverse stories that took real research to uncover.

They interviewed pioneering women of color Alicia Odewale, Ayana Flewellen, and Jewell Humphrey working on the Society of Black Archaeologists–led Estate Little Princess plantation project. They ground their way through the difficulties of transatlantic archival research during a pandemic and national lockdowns to write historical biographies of women such as Gussie White, an educated Black woman who worked as a manual laborer and digger, that sit alongside the histories of her wealthy, White, and much better documented counterparts on the Irene Mound site in Georgia in the 1930s.

It took our students a considerable amount of work to be able to sit down and tell these stories—work that needs to be done and yet somehow is almost always slightly out of funding remits and, therefore, out of reach. There are groups out there dedicated to supporting women in science, but resources for storytelling and documenting remain hard to come by—and they can be inaccessible if you do not hold a position in the traditional academic system.

If the same old stories of “fabulous firsts” get told every Women’s History Month, all it does is perpetuate the myth of the lone genius. This does a massive disservice to the friends, colleagues, mentors, teachers, parents, workers, partners, and pot-washers who support scientists and make science possible. What’s more, it erases the contributions made by anyone who didn’t do science the “right way,” with the right degrees and the right connections.

But it is possible to change that by changing how history is written to include people on the margins and in the marginalia.

The world of science is still very much a closed system, where networks and connections matter. Careers in the “digging” sciences are still propped up on the same pillars of networks and mentorships that they were in the past. Over the years, we at TrowelBlazers have gone from telling the stories of women from our own networks to an almost entirely crowdsourced archive that has massively expanded our scope and our representation of the many faces of science.

To change what the future of science looks like, you first have to change your view of the past. For Women’s History Month, we invite everyone to learn some of the same lessons that we are learning: If you don’t want the future of the “digging” disciplines to reflect a biased past, all of us have to look around at our own networks and do the work to make sure that, when it comes to making archaeology a better and more inclusive field, it’s not just the same old story.