The International Order Is Failing to Protect Palestinian Cultural Heritage

During the first six months of the current war on Gaza, the Israeli military destroyed about 60 percent of the Strip’s cultural heritage sites and monuments. This toll includes the Bronze Age settlement of Tell el-‘Ajjul, the St. Hilarion monastery founded nearly 1,700 years ago, and Pasha’s Palace built in the 13th century and used recently as an archaeological museum. According to many Palestinian and civil rights organizations, this destruction is deliberate.

I’m an archaeologist living in the West Bank who has written about cultural heritage destruction and antiquities looting. I serve as the secretary general of the International Council on Monuments and Sites–Palestine and of the Society for Palestinian Archaeology. Over 34 years, I have conducted several research projects and interviewed hundreds of Palestinians involved in illegal looting, trading, and trafficking of ancient objects.

The losses unfolding now in Palestine, however, are unprecedented in scale and speed.

International agreements enshrine the protection of cultural heritage and recognize its destruction as a war crime. But agencies responsible for policing these agreements have been conspicuously and inexcusably absent from the current conflict.

No doubt protecting historical monuments and archaeological sites is challenging amid a war, and humanitarian efforts should prioritize saving lives. Yet UNESCO and other heritage organizations have tools and tactics to deter the destruction of cultural assets in conflict zones.

Why, then, are these organizations neglecting to protect cultural heritage in Palestine?

PROTECTING HUMANITY’S HERITAGE

Political conflicts and wars ravage societies. While most attention focuses on lost human lives—and rightly so—the destruction of cultural assets is also disastrous.

Cultural heritage includes archaeological sites, historic monuments, artifacts, archives, and museums, all of which hold value for the realms of history, science, aesthetics, religion, and architecture. These elements serve as symbols of collective identity and tangible links to past peoples. Be it an archaeological site, a work of literature, a painting—every cultural asset conveys a narrative of human ingenuity and adaptability.

International bodies have worked to protect cultural property through numerous conventions and protocols. In 2017, for example, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 2347, which condemns the unlawful destruction, looting, and smuggling of cultural heritage by terrorist groups.

Such efforts began over a century ago and include the 1874 Brussels Declaration signed by 15 European nations, the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, and UNESCO’s Recommendation on International Principles Applicable to Archaeological Excavations adopted in 1956.

The first criminal conviction for the intentional destruction of cultural heritage came in 2004 when the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia sentenced a Yugoslav naval commander, Miodrag Jokić, to seven years in prison. In addition to his charges for murder and other crimes, Jokić was found guilty of ordering mortar firing on the historic city of Dubrovnik.

In another judgment in 2016, the International Criminal Court issued a nine-year prison term to a Malian jihadist, Ahmad Al-Faqi Al-Mahdi, who demolished 10 religious monuments in Timbuktu. This ruling was the first to recognize cultural heritage destruction as a war crime.

LOSSES IN PALESTINE

According to Resolution 242, passed by the United Nations Security Council in 1967, the Palestinian territories, which include the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip, are under occupation. As the occupying power, Israel must take necessary measures to safeguard and protect the cultural and natural heritage of the Palestinian territories.

During its 2023–2024 assault on Gaza, Israel has been credibly accused of doing the opposite: systematically destroying Gaza’s cultural heritage as part of its broader genocide of Palestinians in Gaza.

As of February, Israeli forces have destroyed at least 200 archaeological sites and buildings of cultural and historical significance in the Gaza Strip, according to a report from the Palestinian Ministry of Culture.

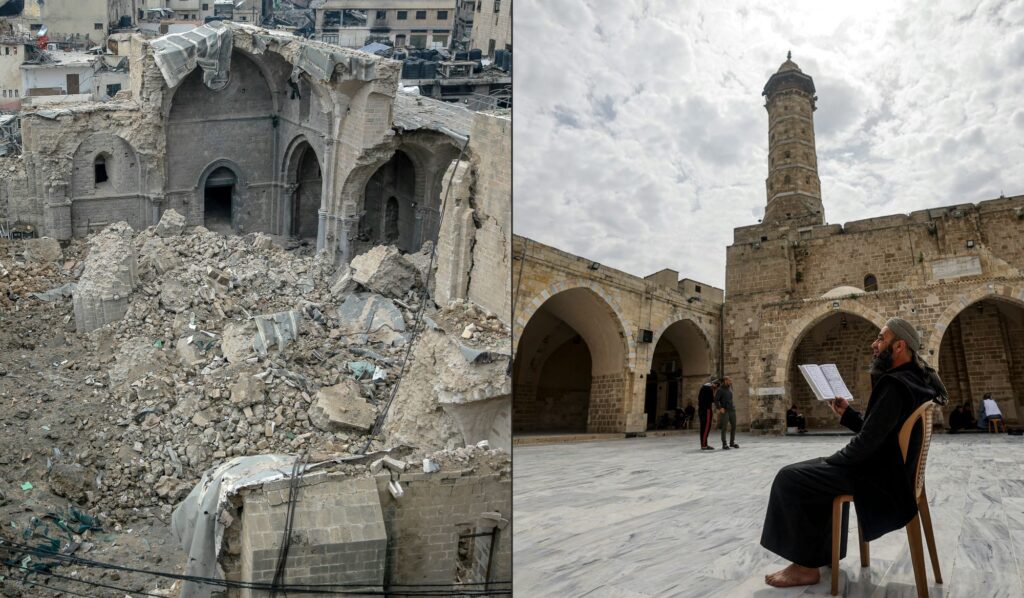

The seventh-century Omari Grand Mosque in Gaza City, with its towering minaret and marble columns, has been severely damaged. The 1,600-year-old Church of St. Porphyrius was thought to be the world’s third-oldest church. An Israeli airstrike collapsed part of the complex, killing at least 17 people inside. The Israeli military bombed and bulldozed part of the archaeological site of Blakhiyya, which served as Gaza’s port from 800 B.C. to A.D. 1100. Archaeological objects from this site were among some 4,000 artifacts in a warehouse that has been seized by Israeli soldiers.

At the same time, in the West Bank, desperate Palestinians have recommenced illegal digging at archaeological sites, hoping to uncover objects to sell on the antiquities black market. The brazen use of bulldozers by some looters has caused significant destruction at sites across the territory. Surveying damages with the director of the Tourism and Antiquities Police Directorate, I witnessed bulldozers used at the sites Tell Qila, Khirbet al-Karmil, Khirbet Arnaba, Beit Nasib, Khirbet Humsa, Khirbet Tarmah, and more.

Plundering and looting drain Palestine’s cultural heritage. Precious objects are stolen from their contexts without documentation, covertly carried across borders, and sold to collectors. With each object that disappears into the shadowy illicit antiquities market, a piece of history is irretrievably lost.

NEGLECTED PROTECTIONS

Difficult in the best of times, protecting cultural heritage can seem impossible during conflicts, characterized by broken governments and life-threatening conditions. Well-intentioned treaties and conventions rarely resonate with those who start wars.

But even in warzones, international organizations such as UNESCO can take actions that deter would-be offenders. They can issue statements of condemnation and send decisive, impartial messages through diplomatic channels to conflicting parties. They can also collaborate with local groups and researchers to gather testimonies, photos, satellite imagery, and other evidence documenting attacks on cultural sites. This evidence can be used to hold perpetrators accountable in the International Criminal Court.

In the current war, UNESCO granted the St. Hilarion monastery in the Gaza Strip provisional enhanced protection status, which strengthens potential punishments for its damage. The organization says it is using satellite data to monitor the monastery.

Aside from these scanty steps, very little has been done by international organizations to save Palestine’s heritage during the current war.

Blue Shield International, the International Council of Museums, the International Council on Archives, Future for Religious Heritage—from what I am aware of, these prominent heritage organizations have stayed silent and uninvolved. The World Archaeologists Congress and the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) issued meek statements that almost appear to support the assault.

UNESCO called “on all actors to scrupulously respect international law” and ICOMOS likewise reminded “all parties involved in the conflict” that the region contains precious and sacred sites. As Palestinian archaeologist Mahmoud Hawari pointed out, these passive statements fail to mention that Israel’s indiscriminate bombing is causing most of the destruction. UNESCO’s words also contrast starkly with a statement the organization released after Russian airstrikes damaged several cultural sites in Odesa, Ukraine, in 2023: “UNESCO is deeply dismayed and condemns in the strongest terms the brazen attack carried out by the Russian forces.”

Where is UNESCO’s strong condemnation of Israeli offenses that have destroyed more than 200 cultural sites and monuments in the Gaza Strip? And where are the calls for more resources to stop the increase in looting and sales of stolen antiquities?

DESTRUCTION AND DOUBLE STANDARDS

An open letter signed in October 2023 by more than 400 individuals who collectively identified as “scholars of antiquity” states: “Israel is overrun with war and is now defending itself. … We, the signatories, stand with Israel.” Apparently, these “scholars of antiquity” seem to believe Israel should be permitted to decimate antiquity as part of its genocide in the Gaza Strip.

These individuals and others have attributed the current conflict entirely to Hamas’ October 7, 2023, attack on Israel. This framing fails to acknowledge decades of history and preceding violence. The annihilation of Palestine’s cultural property did not begin with Israel’s attack on Gaza following October 7. The crimes stretch back generations.

For example, in 1948, when the State of Israel was established, Zionist groups completely or partially destroyed 418 historic Palestinian villages. Over the decades, the causes of cultural heritage destruction have varied, encompassing economic, ideological, and political factors, among other influences.

Read more from the archives: “The Responsibility of Witnesses to Genocide.”

Amid the current war, UNESCO and other organizations supposedly concerned with protecting cultural heritage have done almost nothing effective to deter the ongoing destruction in the Gaza Strip and West Bank. They have failed to live up to their obligations.

For conflicts in Mali and the former Yugoslavia, international organizations prosecuted individuals responsible for destroying cultural assets. Yet no such measures have been applied during Arab-Israeli wars. I and others must conclude the international community is employing a double standard.

I, together with other archaeologists in Palestine, wait despondently for these organizations to act. We urge them to use the tools at their disposal to save what remains of Palestine’s cultural assets, an indivisible part of humanity’s heritage.