History Lost to Sea

On a bright and buggy day in July 2014, Max Friesen, whiskered and encased in denim and Gore-Tex, inched across a stretch of tundra overlooking the East Channel of the Mackenzie River, where it unravels into the Arctic Ocean. The archaeologist pushed his way through a tangle of willow brush that grew thick atop the frozen soil sloping towards the ocean.

Friesen was searching for signs of a long-buried house, feeling for the berms and sharply defined depressions in the ground that pointed to subterranean walls and rooms. The work was difficult and stressful. Shrubs obscured the ground. Friesen had to trust that what he felt beneath his boots was in fact the structure of a large home hundreds of years old.

“I was under horrible pressure,” says Friesen from his office at the University of Toronto a year later. “I had this crew of 10 that I wanted to get digging. But if you make a mistake, you’ve devoted 10 people’s labor for weeks at incredibly high costs to get the project going, and if you came down on a crappy house it would be really terrible.”

But Friesen’s team was not disappointed. They unearthed an enormous cruciform (cross-shaped) pit house built about 400 years ago by the Inuvialuit, the Inuit living in what is now northwestern Canada. Portions of other cruciform houses have been recovered before, but this house is the largest and best preserved one to be fully excavated and examined with modern techniques. Cruciform houses are spoken of in early histories, by elders, and in the writings of early explorers, but none have been studied by archaeologists in such detail, says Friesen. “Nobody since the 19th century has seen these houses.”

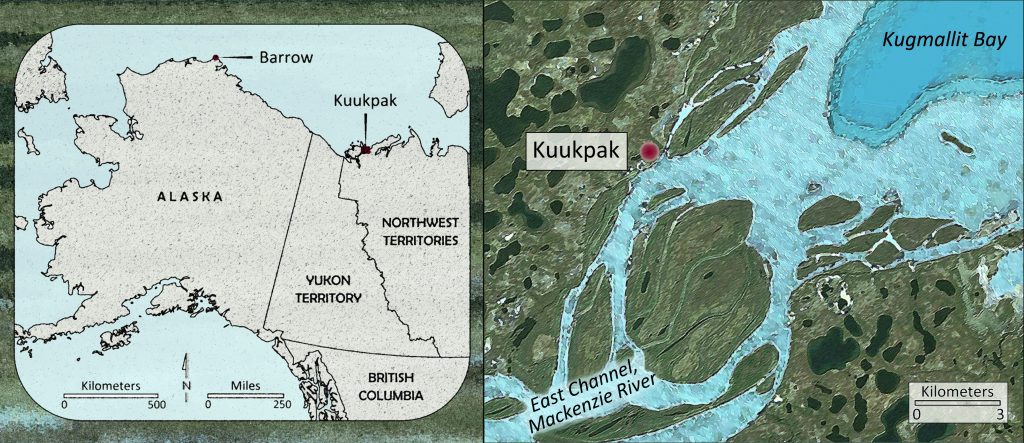

The house is part of a settlement called Kuukpak, a 500-year-old hunting village located above the Arctic Circle in Canada’s Northwest Territories and occupied until the end of the 19th century. Friesen knows Kuukpak well. He first traveled there in 1986 when he was a graduate student, part of a team led by Charles (Chuck) Arnold. At the time, Arnold was the senior archaeologist for the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife. “Kuukpak was the largest archaeological site that I had ever witnessed,” says Arnold.

Exploring the site as a student was transformative, says Friesen, now in his early 50s. “It opened my eyes to the rich history, the incredible preservation of delicate artifacts, and the close relationship between the environment and human settlement.”

After decades away, Friesen has returned to Kuukpak to record the details of the settlement before it is lost to the sea. Coastal archaeological sites like Kuukpak dot the Mackenzie Delta region, but many are unexplored—and they are in the midst of being destroyed by an unrelenting force.

Erosion, permafrost thaw, and rising sea levels brought on by modern climate change are dragging ancient homes and other artifacts into the sea and leaving them exposed to rot on land. The coastline along the Beaufort Sea has been eroding for thousands of years, but in recent decades its contours are being reshaped more swiftly—by as much as 20 meters in a single storm. “The people in Tuktoyaktuk are horrifyingly aware of the erosion. They go out in the summers to hunt and fish and they see the sites eroding,” says Friesen. The effects of climate change are more severe in the Arctic, where air temperatures are warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. Historical villages are being swallowed whole, along with piles of unstudied artifacts from early Inuvialuit culture.

“If you take the sum of the impacts, the thawing permafrost and the coastal erosion of the high Arctic, the sum of that archaeological loss is really awful,” says Tom Andrews, territorial archaeologist for the Northwest Territories government. “It’s really a disaster.”

The rapidly shifting climate has transformed views about archaeology in the region, and the Inuvialuit have embraced the renewed activity. In the past, some elders opposed excavating archaeological sites because artifacts were often shuttled away to museums and research centers in the south. “Now, because we’re losing the sites, [the Inuvialuit] are all for the archaeology,” says Catherine Cockney, the manager of the Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre in Inuvik, Northwest Territories.

In 2013, Friesen began a survey of the western Canadian Arctic to understand which settlement sites were under threat from climate change. He worked with the resource center to identify which sites the Inuvialuit consider to be most important, based on their oral histories, and which ones are most threatened by climate change. Kuukpak topped the list.

Kuukpak sits on the Mackenzie Delta, and its name means “big river.” From 1500 to 1900, it was the main winter village for the Kuukpangmiut—the people of Kuukpak—a large and powerful regional group. Kuukpak was probably the largest village in the Inuvialuit region—and in all of Arctic Canada—stretching almost a kilometer along the bank of the Mackenzie. “It would have been the site of the biggest hunting events, ceremonies, and social activities,” says Friesen.

The people who lived in Kuukpak traded goods, arranged marriages, and organized social gatherings with other Inuvialuit groups living in the western Canadian Arctic. Each group—eight in all—had its own central village and defended its territory. They had distinct dialects and sewed, dyed, and decorated their clothes in different styles, says Cockney.

The location of Kuukpak, where the Mackenzie River spills into the sea, provided the families living there with an abundance of food. They had access to caribou on the mainland and fish in the rivers and creeks. But it was the beluga whales that were the real draw.

In the spring, belugas swim from the Bering Sea along Alaska’s north coast towards the Mackenzie. The stocky white whales, weighing as much as 1,500 kilograms and measuring up to 6 meters in length, arrive in the estuary in late June or early July seeking out the warmer and less salty water to molt, feed, and give birth. The calves are born gray or brown, and their color fades to white as they mature. “Kuukpak is in exactly the perfect spot to hunt beluga whales,” says Friesen. “There are enormous shallows. You can walk out quite a ways and be only up to your knees.”

When the belugas came close to shore, lines of kayakers paddled out to the mouth of the bay to drive the whales into the shallows where they speared the animals. According to historical accounts from the late 1800s, as many as 300 belugas were harvested in a single summer. The women butchered the animals, separating their dark red meat from the thick skin and fat. The inner layer of skin and meat was eaten. The blubber was often rendered into cooking oil. The meat was hung to dry and later stocked in caches dug deep into the permafrost. The Kuukpangmiut transformed the inner layer of beluga skin into leather and used it for boat covers and footwear.

In the winter, during the darkest months—when the sun barely grazed the horizon—the families went to Kuukpak and lived in sod houses, embedded into the permafrost, with walls, floors, and the roof built with driftwood plucked from the Mackenzie River.

When Friesen returned to Kuukpak during the summer of 2014, he found a visibly crumbling coastline and the site thick with stunted willows. The team worked tirelessly for six weeks, often in a cold drizzle, to uncover the cruciform house. The collapsed house was wedged deep in the permafrost, so digging it out was laborious. But slowly, the structure began to surface. “It was spectacular to see it come up,” says Friesen.

The house is unusually large. Shaped like a long cross, it has a central living area surrounded by three raised alcoves. An extended tunnel provided access to the house but kept the cold air out in the winter. The main room measures 6 to 7 meters wide and 5 to 6 meters long. Thirty people may have once lived in the house. Friesen says this type of winter house was well known in Inuvialuit traditional knowledge, but has rarely been studied and is poorly understood.

Inside, Friesen and his team found hundreds of artifacts related to hunting, clothing production, food preparation, and house construction, along with thousands of animal bones. Arrowheads and harpoon heads, needles and stone scrapers, ulus (knives with a curved rocker edge) and snow knives littered the site. Trade goods, including soapstone and copper, were also preserved inside the house. The artifacts, combined with the bones of beluga whales, fish, caribou, migratory birds, and seal suggest that the people living there—and their society—were well off. “It was a rich, rich house,” says Friesen.

But the house was so large that Friesen and his team were unable to complete the excavation in 2014. At the end of the field season, they backfilled the pit to preserve the contents. They plan to finish the dig this summer and add artifacts to their collection before completing the analysis. Friesen is eager to inspect the artifacts from each of the three alcoves to understand who lived there and how the alcoves were used.

Before leaving in 2014, Friesen’s team started excavating a house on a bank that had already begun to tip onto the beach. On the floor and on a bench inside, they found a treasure: 10 trade beads dating to the 1800s. Oral history indicated that Kuukpak had been occupied until the mid- to late 19th century, but archaeologists lacked any proof until that moment.

In the late 1800s, Kuukpak was abandoned, its population likely decimated by infectious disease brought by interactions with European whalers who overwintered close to Inuvialuit settlements. “Until now, there has never been a house, a nice sealed context, that allows us to look at what degree, which aspects of society were changing at this time,” says Friesen.

Friesen estimates that 40 houses once stood at Kuukpak, though only 23 dwellings remain. The rest have been lost to the ocean. Looking up from the beach, driftwood, beluga bones, and other objects jut out from the overhang. They’re a reminder of the village’s distinction—and of how much is already gone.

There is no practical way to preserve Kuukpak. The sod houses are too delicate to relocate, and once they are exposed to air, they begin to rot. However, Peter Dawson, an archaeologist at the University of Calgary, has digitally scanned one of the exposed houses to create a permanent architectural record. In theory, a home could be reconstructed with modern driftwood and sod.

“When I first came up here, there were people who had grown up in sod houses,” says Anne Jensen, an archaeologist at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks, who lives in Barrow. “But now the young ones have never seen that kind of house. The ability to go and set foot in one and see it—they have a much, much greater appreciation for how tough it was for their grandparents, and how incredible and cool they were.”

In 2014, Friesen hammered stakes into the ground at Kuukpak so that he could track the coastline’s rate of erosion, and in the summer of 2015 he stopped by to check on the site. One location, which had badly eroded in the past, was still stable, but the erosion edge of another had suddenly advanced by a meter in one year.

“I thought the house would last 10, 20, or 30 years, but maybe it’s only going to last for three years,” says Friesen. “And maybe it is the only remaining intact house from that period—anywhere.”

This article was republished on discovermagazine.com.