Trump and the Echo of Amache

In the southeastern corner of Colorado, not far from the Kansas border, there isn’t much to see besides cattle ranches and farms. But turn south on County Road 23 5/10, just outside of Granada, and the tall grass and cacti give way to the remains of a small makeshift town. Here, near America’s heartland, is the Granada War Relocation Center—little more than a dot on some maps, and absent from most, but a crucial reminder of how prejudice and discrimination have shaped America’s story.

Established during World War II, this former internment camp for Japanese-Americans, known as Amache, is a desolate place on the high prairie. (It’s located about one hour from the site of the 1864 Sand Creek massacre—another scar on our nation’s history that is rarely discussed.) Amache has long been abandoned, but the cement slabs supporting the shower and laundry facilities, the barrack foundations, and the base anchors for the guard towers remain visible.

Inspired by the first pilgrimages to Manzanar—another internment camp located near Death Valley, in California—the Asian American Community Action Research Program (CARP) initiated the pilgrimages to Amache in 1976 for those who wanted to remember and honor the site. Beginning with the first generation Japanese-Americans (issei), the second and third generations (nisei and sansei, respectively) have continued to return to Amache for what is now an annual pilgrimage. For three years during the height of the war, this was home to thousands of people. In a bleak landscape of little shade and high winds, the heat has seared the mistakes of the past into this remote terrain.

This past July, I went to Amache to interview some of the former internees and volunteers during the pilgrimage. I asked them questions about life at Amache and about their own memories of internment (that is, the confinement or detention of people, especially during wartime). More specifically, I wanted to explore whether there are any meaningful connections between the history of the internment camps and the wave of anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant sentiments currently being fueled by Donald Trump, the Republican nominee for president.

One of the people I met at Amache was Carlene Tanigoshi Tinker, a retired educator who now lives in California. She and a number of other former internees were there to participate in an event hosted by the University of Denver Amache Research Project. The project has been directed by Bonnie Clark, associate professor of anthropology, since 2008. This occasion was an opportunity for former detainees of Amache to work alongside students and faculty in an archaeological investigation of the site. At one point, as Tinker and I walked through the ruins of her family’s barrack, I asked her what she thought about the current situation in the U.S., and she said, “it’s worrisome to think about how little has changed in our society.” She hopes the research will shed light on a chapter of our nation’s history that has too easily been forgotten by most Americans.

After Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the FBI and the Office of Naval Intelligence regularly conducted surveillance on Japanese-American communities in Hawaii and on the U.S. mainland. In 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt secretly commissioned the Munson Report to assess the potential threat of Japanese-Americans to U.S. security (particularly on the West Coast). The report, which was submitted to President Roosevelt one month before the bombing of Pearl Harbor, argued that “There is no Japanese ‘problem’ on the Coast. There will be no armed uprising of Japanese,” and that the vast majority of Japanese-Americans posed no threat to the country’s security.

Nonetheless, a few months after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which led to the mass removal of Japanese-Americans from the Pacific Rim states—California, Oregon, and Washington—without due process. They were to be moved to facilities that Roosevelt, in another context, called “concentration camps.” As a result, more than 120,000 Japanese-Americans were removed from their homes and held in internment camps around the country. Approximately one-third of the internees were children.

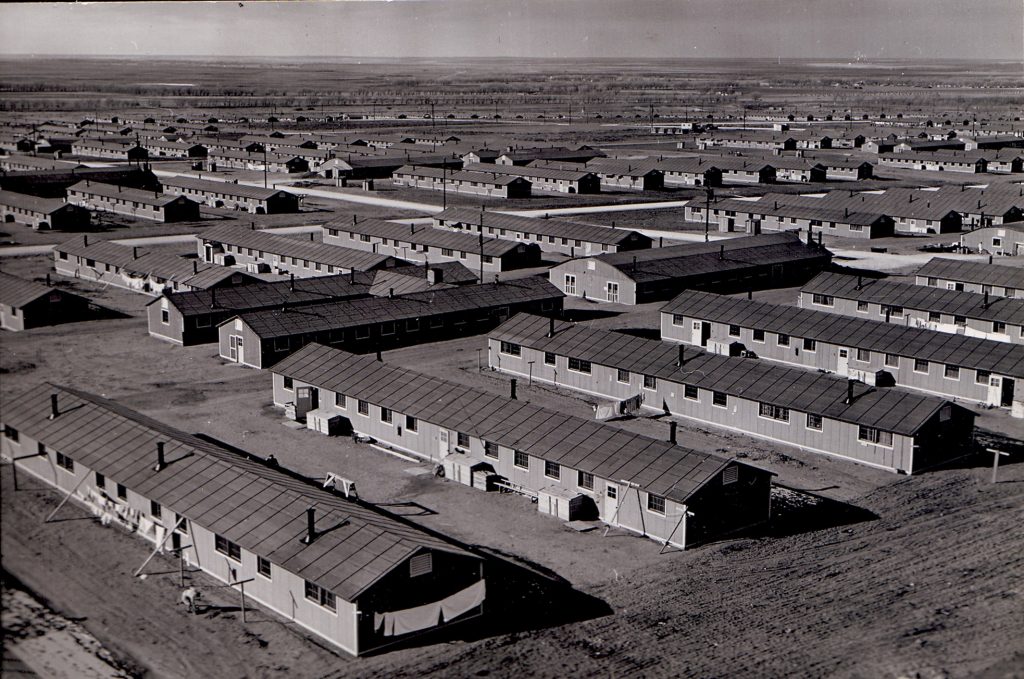

The U.S. War Relocation Authority established 10 camps in remote areas of Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming. The total area of Amache encompassed 16 square miles encircling the town of Granada. By the end of October 1942, more than 7,000 Japanese-Americans, nearly all of whom came from California, had arrived.

The central section of Camp Amache was comprised of 29 blocks of Army-style barracks. Each block included a shower room, mess hall, toilets, and laundry. The shared administrative facilities—such as a post office, hospital, public library, school, recreation buildings, and dry goods store—were distributed throughout the camp. After gaining approval from the staff, internees built gardens and koi ponds and planted trees between the barracks. The facilities were also fenced with barbed wire and guarded by armed soldiers. “They were there with their guns,” Anita Miyamoto Miller, another former internee, told me.

If you ask the people who called Amache home, the language put forth by Trump and others of his ilk in the U.S. is disturbingly similar to the language used to refer to Japanese-Americans more than 70 years ago. In response to the bombing of Pearl Harbor, a Congressman at the time, John Rankin, implored, “I’m for catching every Japanese in America, Alaska, and Hawaii now and putting them in concentration camps. … Damn them! Let’s get rid of them now!” Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson expressed similar sentiments: “Their racial characteristics are such that we cannot understand or trust even the citizen Japanese.”

Some of the inflammatory rhetoric used today revives such exaggeration and paranoia. In February, protestors held a rally at the Missoula County Courthouse to raise their objections to allowing Syrian refugees into Montana. One protestor carried a sign that read, “No Muslim refugees in Montana.” At an anti-refugee demonstration in Helena later in the month, one participant’s sign stated, “No more refugees or unsecured borders.”

Ray Hawk, chair of Montana’s Ravalli County Commission, adapted Donald Trump Jr.’s widely scorned Skittles metaphor to explain the strong views of his constituents, who are adamantly opposed to allowing refugees into the state. “There was a lot of sentiment against those refugees. We have no way to know what you’re getting,” he said, in an October interview. “Like somebody bringing in a bowl of jelly beans and putting them on your table and say take all you want, but two of those in there are cyanide.”

On June 12, soon after 49 people were killed in a mass shooting at a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, Trump posted tweets thanking his followers for the “congrats for being right on radical Islamic terrorism” and again calling for a ban on allowing Muslims into the United States.

In mid-October, three Kansas men were arrested by the FBI and subsequently charged with plotting to carry out an attack within the state on Muslims in an apartment complex and a mosque as well as on immigrants from Somalia who are Muslim. According to the FBI, “the Crusaders” were planning to target churches that had previously supported refugees, as well as landlords who were known to have rented their properties to Muslim refugees. For Patrick Stein, one of the members of the domestic terrorist group, “The only good Muslim is a dead Muslim.”

By the early 1940s, Asian-Americans had long been widely characterized in the U.S. and elsewhere as the “yellow peril.” Before World War II, a number of laws prevented Asian-Americans from owning land in many states, voting, and testifying against whites in court. Despite this history of institutional racism, when the internment camps were established some officials claimed that incarceration was meant to “protect” Japanese-Americans from racist retribution after Pearl Harbor.

However, it was also well-known that agricultural interest groups along the West Coast and in Arizona had long been keen on removing Japanese-Americans from their farmlands. Laurence Hewes Jr., the regional director of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) during World War II, was tasked with handling the confiscation and sale of Japanese-American land holdings after people were removed from them. In all, FSA field agents seized more than 6,000 farms totaling approximately 200,000 acres.

For many Japanese-Americans, farming was all they knew. Before her family was sent to Amache, Miller’s father worked more than 1,000 acres along with a couple of other people, she said. But those who remained “were not willing to keep his part so he could go back to it” after the war. Once the camp closed, her father had to start again with some 45 acres.

“Evacuated” families left behind homes, businesses, pets, land, and most of their belongings. In many cases, homes were looted and confiscated before the people were forcibly relocated. Many homes and household furnishings had to be sold far below market value.

Despite the harrowing circumstances, the Japanese-Americans incarcerated at Amache ran the camp (under the supervision of Project Director James G. Lindley) as if it were a small town. The inmates held school dances, operated a silkscreen shop, and labored in the agricultural fields. Workers were given a stipend between US$12 and US$19 a month, depending on their skill level. They worked hard to beautify their surroundings, making a wide range of decorative items for their bare units, which included an unfinished closet, steel cots, and a coal-fired heater.

Amache was spread out atop a low hill in an area that is prone to high winds, dust storms, and severe thunderstorms known to sometimes deliver golf ball–sized hail. “Because of the wind here, my dad was very solicitous,” Tinker said. “He would put me on his shoulders and put scarves over my face so I wouldn’t get sand in my mouth.”

I got a taste of the local weather on the day I met the former internees. That morning I was scheduled to interview Tinker at an area she was helping to excavate. The team was digging outside one of the barracks to learn how the individuals who lived there transformed their outdoor space. To the west, we could see that a storm was headed our way. Adam Hopper, one of the high school volunteers from Granada, looked at his weather app and said the storm would arrive in two hours. In less than 30 minutes, I was cursing myself for trusting a weather app.

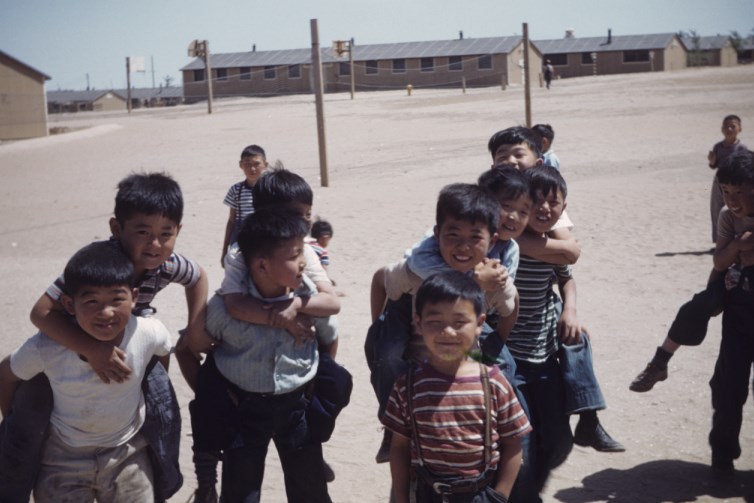

After we hastily packed our equipment, the team sought cover in one of the reconstructed barracks. Once inside, I met Tooru Nakahira, a modest man with calm, soothing eyes. Nakahira called the original barrack home while he was in camp. The pounding of rain and hail on the barrack roof brought back memories. “I occasionally remember the rainstorms,” he said, “but I remember the snow. Especially the snow fights between the boys and girls.” As he walked through the barrack, Nakahira told stories of the games he would play with the other children. “And oh!” he stopped mid-sentence and walked toward the barrack window. “We used to play in the watchtower. We used to climb up to the very top. That was our clubhouse.”

While the Japanese-Americans interned at Amache made the best of their situation—and did everything they could to allow their children to continue to have good lives—there is no denying the shame of being incarcerated on account of their heritage. Many people have chosen to never talk about their life at Amache. It’s too painful for them. In the detention centers, families lived in substandard housing and suffered from inadequate nutrition and health care. For most, the process of removal and relocation destroyed their livelihoods. Many continued to suffer from psychological and emotional damage long after their release. But for those who have chosen to return for the pilgrimage, it’s an opportunity to reflect on the past, present, and future.

It’s also a chance to think about what it means to be an American of Japanese descent. After a week at Amache, I spoke with Greg Kitajima, a Japanese-garden specialist whose parents, aunt, and grandparents were interned at the camp. His family never spoke about life there. They wouldn’t discuss it, no matter how hard he tried to encourage them.

For Kitajima, visiting Amache was an opportunity to learn about the gardens the internees had constructed. “They were so limited in what they had,” he said. “They had no natural rock, so the use of concrete slabs is reflective of the Japanese-American spirit.” What he learned about the gardens at Amache made him extremely proud of his heritage. The gardens helped him understand how those who lived there moved from an attitude of acceptance and resignation—“It cannot be helped” (Shikata ga nai)—to one that showed “perseverance and fortitude,” or gaman.

For the people who lived at Amache, the gardens were a form of place-making that allowed them to transform their stark surroundings into a landscape that was more familiar to them. “At Amache, these guys were not trained,” Kitajima said, “but they pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, took what they had, and made something out of it.”

The remnants evidencing prejudice and discrimination can be found in the barbed wire that encloses the camp cemetery at Amache, where wooden planks carefully inscribed in Japanese list the names of those who died there. But the former camp also reveals the strength of the human spirit. Internees transformed the camp at every imaginable level, from the interiors of the barracks to the landscape itself. With the approval and support of Lindley, they built sidewalks, constructed playgrounds and sports facilities, installed intimate lighting systems, and planted trees to beautify the landscape.

The Japanese-Americans who were relocated during World War II made the best of a terrible situation, but that doesn’t mean their internment was acceptable. The internment camps should never have been established. A federal study in the 1980s found no justification in military necessity for the incarceration of Japanese-Americans, which was caused by “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

Given the surge in Islamophobia driven by anti-Muslim rhetoric, it is vital that we remember—and think hard about—places like Amache and how they came to be. Trump has repeatedly called for a ban on Muslims entering the United States. Arguing against allowing Syrian refugees into Virginia, David Bowers, who was the mayor of Roanoke, Virginia, at the time, referenced the internment camps of Japanese-Americans during World War II. “I’m reminded that President Franklin D. Roosevelt felt compelled to sequester Japanese foreign nationals after the bombing of Pearl Harbor,” Bowers wrote, “and it appears that the threat of harm to America from ISIS now is just as real and serious as that from our enemies then.”

After extensive interrogations, none of the internees at Amache were found guilty of espionage. The “threat” was an illusion then just as it’s an illusion now. Not only is it grossly inaccurate to link all Muslims to the terrorist attacks committed by the Islamic State group and other extremist groups—it’s irresponsible.

In a June interview, Republican Party strategist Mike Murphy was asked how Trump came to be the Republican nominee for president. “Archaeologists will be studying the ruins for a while,” he ventured. Let’s hope American citizens never have to look back on a past haunted by Muslim detention centers in the U.S. or a great wall of Trump.