The Ethical Battle Over Ancient DNA

In February, scientists published a critically important contribution to our understanding of the ancient Pueblo peoples of the American Southwest. A 14-member interdisciplinary team, including anthropologists, archaeologists, and geneticists, succeeded in extracting and sequencing DNA from the remains of numerous individuals who were apparently elite people at Chaco Canyon, the wondrous archaeological complex in northwest New Mexico. In its heyday, about A.D. 800 to A.D. 1150, Chaco was at the center of one of the richest and most sophisticated civilizations to grace North America before European colonists arrived in the 16th century. Its cultural influence spread throughout what is today known as the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado, and possibly as far south as modern-day Mexico.

The findings, which provide important insights into the social structure of the ancient Puebloans, have sparked considerable excitement among archaeologists and others who study the ancient past. One might think their enthusiasm would be shared by present-day Pueblo peoples, who claim the Chacoans as their ancestors—a contention strongly backed by archaeological evidence.

But instead, news of the research, which was published in the journal Nature Communications, has made some Native American tribal officials very angry. In contrast to other recent cases in which scientists have consulted tribal peoples and obtained their blessings before extracting DNA from ancestral Native American remains, the researchers are only now discussing their results with tribal groups. To a number of critics, including some researchers, the controversy represents a setback to recent progress in fostering collaborations between scientists and tribal peoples.

“It is clearly ethically problematic to carry out destructive analyses on Indigenous human remains without talking to any Native peoples about it,” says archaeologist Ruth Van Dyke, a Chaco researcher at Binghamton University in upstate New York. “In recent decades, archaeologists have been working hard to build trusting, collaborative relationships with our Indigenous colleagues. Any research that fails to respect Native rights and sensibilities can only undermine this progress.”

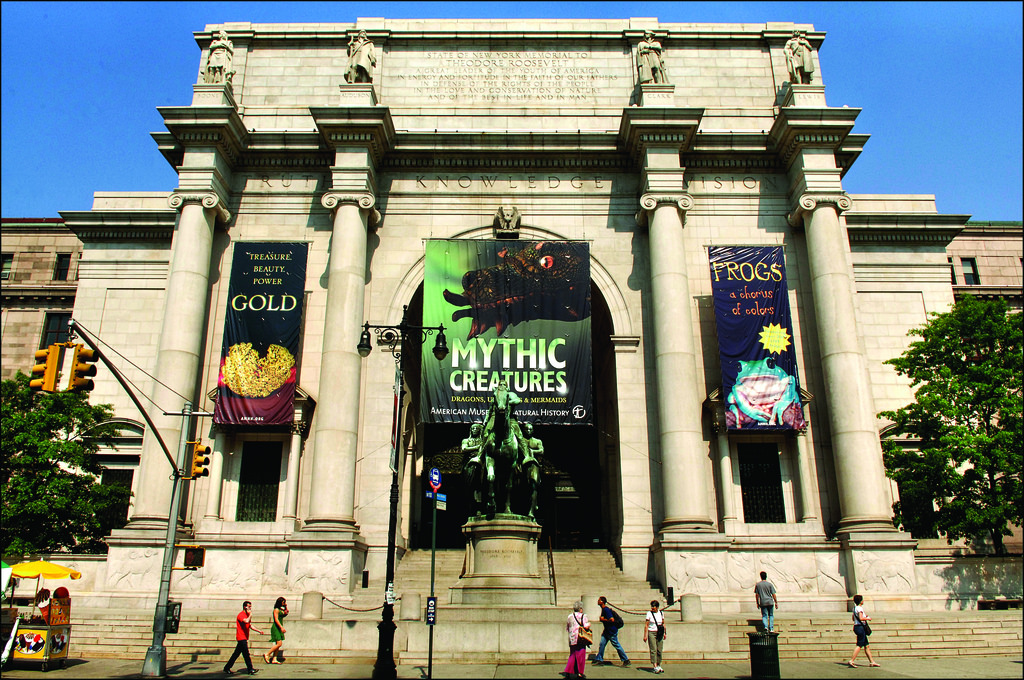

The episode is all the more troubling because it involves a renowned institution, the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), which has held these ancient Puebloan remains in its collection since they were first excavated in the late 1890s. Yet the museum has been tight-lipped, both about the basis on which it granted the team permission to carry out this recent research as well as about an earlier review, formalized in 2000, of the legal status of these human remains. It has released only a brief statement and declined to make public the detailed documentation that supposedly backed up these decisions. Nevertheless, this author has obtained the 2000 document, a detailed inventory and review of the remains that was mandated under federal law. The AMNH’s review, which was conducted during the late 1990s, concluded that the bones were “culturally unidentifiable”—that is, they could not be linked directly to any living tribal group.

The museum seems to have fulfilled at least the letter of the law. The law that mandated the review, the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), requires all public and private museums that receive federal funds (except the Smithsonian Institution) to inventory Native American artifacts and human remains in their possession and to consult with tribal groups that might want to claim them. In its statement to the author, the AMNH asserted that during the latter half of the 1990s it had attempted to contact southwestern tribes about the human remains it held but that none had made a claim of affiliation with them.

Museum officials declined to elaborate on exactly who they had contacted and how hard they had tried, however. In practice, the law gives institutions a great deal of latitude in how they interpret its requirements. Thus tribal groups have sometimes had to go to court to prove that they are culturally affiliated with particular human remains or cultural items in museum collections. Although current federal regulations interpreting NAGPRA dictate that the tribes can win such cases if the “preponderance of the evidence” leans in their favor, even that somewhat generous standard can sometimes be hard for tribal groups to meet.

But if the AMNH fulfilled the letter of the law, the question remains whether it fulfilled the law’s spirit of respect for tribal cultural traditions. The museum submitted its review to NAGPRA authorities in June of 2000. A great deal has happened since, including the repatriation and reburial of the famed Kennewick Man—known as the Ancient One to the Native American tribes who claimed him—after nearly 20 years of battles between tribal groups and some scientists. Some anthropologists had argued, based on analysis of his skull shape, that Kennewick Man was most closely related to people from Polynesia or the Ainu ethnic group of Japan, and not genetically related to contemporary Native Americans. In that case, ironically, the DNA results provided key evidence that the 8,500-year-old Ancient One, who was found in 1996 by the Columbia River in the state of Washington, was indeed genetically close to present-day Native Americans, including one of the local tribes that was claiming him.

But the AMNH apparently made little or no attempt to bring its 2000 review up to date. Prior to approving the new DNA research, the museum, according to its own statement, did not revisit the review’s nearly 20-year-old conclusions, nor did it consult with either contemporary Pueblo groups or representatives of the Navajo Nation, which today surrounds the federally protected Chaco Culture National Historical Park. (The Navajo also claim the Chaco people as their ancestors, although that contention is seen as controversial by some.) The AMNH’s explanation for not consulting with the tribes before granting the team permission to do its research is “unacceptable” given NAGPRA’s long history, says Kurt Dongoske, the tribal historic preservation officer for the Pueblo of Zuni in northwest New Mexico. “It has been 27 years since the passage of NAGPRA, and a lot of tension, disagreements, learning, and cultural and historical sensitivity training has been experienced by tribes, museums, and federal agencies.”

It’s understandable that researchers would want to find out as much as they can about the far-flung “Chaco world” and its rich architecture and culture. Here in Chaco Canyon, under New Mexico’s bluer-than-blue sky, visitors can walk among the haunting ruins of this great civilization. More than a dozen massive “great houses” line the canyon, each constructed with skillfully cut wooden beams and intricately laid stone bricks that would be the pride of modern carpenters and masons.

During an 1896 expedition, archaeologists broke into a small burial crypt in the most spectacular of these great houses, called Pueblo Bonito, which had more than 600 rooms and was, in one part, four stories high. They found 14 individuals crammed into the crypt. The two earliest burials were adorned with thousands of turquoise beads, and other human remains were associated with artifacts that included pottery and delicately carved flutes and ceremonial staffs. Archaeologists have long suspected that these individuals belonged to an elite group because more turquoise was found in this one crypt than in most other southwestern sites put together.

For the new study, the research team, led by archaeologists Douglas Kennett of Pennsylvania State University and Stephen Plog of the University of Virginia, directly radiocarbon dated the bones of 11 of the burials and extracted DNA from nine of them. The DNA sequences revealed a long-hidden surprise: The Pueblo Bonito elite all shared the same maternal ancestor, whose DNA had been passed down from generation to generation over more than 300 years. This so-called matrilineal inheritance, the research team pointed out, is similar to the traditional social structure of the Zuni, Hopi, Acoma, and other Pueblo groups of the Southwest. These DNA results could bolster existing archaeological evidence that present-day Puebloans are the direct descendants of the ancient Chacoans, especially if some tribal people were now willing to donate DNA samples for comparison. Indeed, such further studies might provide genetic evidence for the cultural affiliation between Chaco peoples and modern Puebloans that the AMNH’s review in 2000 failed to find.

Just such genetic evidence clinched the case of Kennewick Man, whose 8,500-year-old genome was sequenced by ancient DNA expert Eske Willerslev, from Denmark, and his colleagues. Before extracting and analyzing the ancient DNA, however, Willerslev began a lengthy consultation with the five Washington state tribes who had claimed the Ancient One, in vain, for nearly two decades. Willerslev urged them to donate their own DNA samples for the study. While only one tribe, the Colville, agreed to do so, providing two dozen samples, Willerslev’s group found not only that the Ancient One was a true Native American but that the Colville were closely related to him. Although some experts questioned just how close that relationship really was, and whether it was intimate enough for the Colville to claim he was their direct ancestor, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which had formal custody of Kennewick Man, was apparently convinced by the DNA evidence. Last December, President Barack Obama signed legislation passed by Congress authorizing the return of the Ancient One to the tribes, and on February 18, he was buried in a secret location not far from where he was found.

“The time when scientists should go and study ancient human remains from the Americas without some kind of tribal engagement has passed,” Willerslev says. “For many tribal groups, human remains from the Americas are considered ancestors whether or not there is evidence of cultural or genetic links.” Ignoring tribal consultation, he adds, “can no longer be explained by lack of awareness. It’s a decision, and must be considered a statement.”

Most importantly, a growing number of researchers are realizing that the strong feelings Native Americans have about the remains of their ancestors do not reflect an anti-science perspective. Native Americans are keenly interested in their history and prehistory, and, under the right circumstances, they have been increasingly willing to cooperate with scientific studies—if, that is, scientists respect their traditions and do not fall back on earlier colonialist attitudes that allowed archaeologists to strip whatever they wanted from ancient sites.

In a joint statement released shortly before their paper was published, the scientists on the research team—all of whom are based in institutions on the U.S. East Coast—said that they had relied on the AMNH’s determination that the Chaco human remains could not be traced to specific tribes. In a later statement to this author, Kennett said that “the AMNH specifically requested that they be the ones to handle” the cultural affiliation issues, adding that his team had “every reason to think that the AMNH were careful about this and they have great expertise in this area and we deferred to them here.”

In the museum’s own statement, the AMNH said that the team’s research proposal had been reviewed by its Anthropology Loan Committee and approved because “the research had considerable scientific merit with little impact on the artifacts and human remains,” adding that during its 1990s review no tribes “came forward to claim affiliation.”

However, the AMNH’s 1990s review contains no evidence that the museum attempted to consult with tribal groups about potential affiliations with the Chaco human remains it held, despite NAGPRA’s requirement that it do so. Rather, the 14-page document, which lists details about all of the Chaco remains in its possession, argues in general terms that “while most or all pueblos may have some association with Ancestral Puebloan peoples of [New Mexico’s] San Juan Basin, including similarities in ceramics, architecture, and subsistence practices, the nature of that connection is not sufficiently clear to warrant making a determination of ‘cultural affiliation’ within the meaning of NAGPRA to all the Puebloan groups in New Mexico and Arizona.”

The AMNH has declined to discuss these conclusions beyond its original brief statement. However, Leigh Kuwanwisiwma, who has been the director of cultural preservation for the Hopi Tribe in Arizona since 1989, says that the museum never contacted him or the Hopi Tribe during its 1990s review. That is all the more surprising because at that time Chaco national park was engaged in an intensive, controversial, and very public consultation with all of the Pueblo tribes and the Navajo over the cultural affiliation of more than 280 human remains in its own collection. Eventually, the National Park Service determined that the remains were affiliated with more than 20 Pueblo tribes and the Navajo, a decision upheld by the U.S. Department of the Interior. In 2006, the Park Service handed the remains over to tribal groups, who reburied them in a secret location in Chaco Canyon. (Other museums, including the Museum of Natural History at the University of Colorado, Boulder, have come to similar conclusions about Chaco remains in their possession.)

In the current case of the Pueblo Bonito burials, Kuwanwisiwma says, the news of the ancient DNA results came as a complete surprise. “Absolutely no one told me” that ancient DNA would be extracted from the remains, he says. “The tribe never gave any kind of permission or support.” Kuwanwisiwma says the matter is now being discussed among some of the Pueblo groups, particularly the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, and Santa Clara pueblos, and that the All Pueblo Council of Governors has also taken up the matter. “It has clearly been the position of tribes in the U.S., and particularly in the Southwest, that we have never supported destructive DNA analysis.”

As for whether Native Americans might eventually cooperate with the research team, for example by providing DNA samples for comparison, as the Colville Tribe did in the case of Kennewick Man, Kuwanwisiwma says it is too soon to know. That decision, he adds, would depend on whether the Hopi and other Pueblo groups would ultimately benefit from such a step.

And for Dongoske from the Pueblo of Zuni, the central issue is whether the tools of science necessarily trump the traditional knowledge of Indigenous peoples passed down over the ages. “Native Americans do not need scientists to tell them their heritage,” he says. “Their heritage has been passed down to them in oral history, through the recitation of prayers, and in ceremonial traditions. To claim that the Western knowledge system, science, is the only legitimate way of knowing the past is insulting to all of us and it perpetuates the insidious effects of colonialism on Native Americans.”

Can science and Indigenous cultural traditions be reconciled? Perhaps they cannot—or at least not in every case and not entirely. But the story of the Ancient One and other recent cases of collaboration between ancient DNA researchers and Native Americans show that the interests of both groups can sometimes overlap. Indeed, there are signs that at least some of the Chaco team members are now realizing that. “I personally wish that as authors we had communicated earlier on in the study with potentially interested Native American pueblos and tribes to obtain their perspectives in addition to our interactions with the AMNH,” says George Perry, the Pennsylvania State University paleogeneticist who conducted the principal ancient DNA analyses for the team.

Such engagement with tribal groups may well be necessary if the team is to continue its research, which could involve possible ancient DNA analysis of other human remains from Pueblo Bonito, most of which are held by the Washington, D.C.–based Smithsonian Institution. But real engagement and consultation means that museums must be willing to take the risk that their long-held collections of Native American remains—which some living peoples consider to be those of their ancestors—may have to be given back and returned to the Earth from which they came.

Correction: April 3, 2017

An earlier version of this article stated that the Chaco civilization’s cultural influence spread throughout the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado, and possibly as far south as Mexico. This has been updated to make it clear that its influence spread throughout what is today known as the Four Corners region and modern-day Mexico.