Did an Asteroid Shape This Famous Biblical Story?

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

As the inhabitants of an ancient Middle Eastern city now called Tall el-Hammam went about their daily business one day about 3,600 years ago, they had no idea an unseen icy space rock was speeding toward them at about 38,000 mph.

Flashing through the atmosphere, the rock exploded in a massive fireball about 2.5 miles above the ground. The blast was around 1,000 times more powerful than the Hiroshima atomic bomb. The shocked city dwellers who stared at it were blinded instantly. Air temperatures rapidly rose above 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit. Clothing and wood immediately burst into flames. Swords, spears, mudbricks, and pottery began to melt. Almost immediately, the entire city was on fire.

Some seconds later, a massive shockwave smashed into the city. Moving at about 740 mph, it was more powerful than the worst tornado ever recorded. The deadly winds ripped through the city, demolishing every building. They sheared off the top 40 feet of the four-story palace and blew the jumbled debris into the next valley. None of the 8,000 people or any animals within the city survived—their bodies were torn apart, and their bones were blasted into small fragments.

About a minute later, 14 miles to the west of Tall el-Hammam, winds from the blast hit the biblical city of Jericho. Jericho’s walls came tumbling down, and the city burned to the ground.

It all sounds like the climax of an edge-of-your-seat Hollywood disaster movie. How do we know that all of this actually happened near the Dead Sea in Jordan millennia ago?

Getting answers required nearly 15 years of painstaking excavations by hundreds of people. It also involved detailed analyses of excavated material by more than two dozen scientists in Canada, the Czech Republic, and 10 states in the U.S. When our group finally published the evidence recently in the journal Scientific Reports, the 21 co-authors included archaeologists, geologists, geochemists, geomorphologists, mineralogists, paleobotanists, sedimentologists, cosmic-impact experts, and medical doctors.

Here’s how we built up this picture of devastation in the past.

FIRESTORM THROUGHOUT THE CITY

Years ago, when archaeologists looked out over excavations of the ruined city, they could see a dark, roughly 5-foot-thick jumbled layer of charcoal, ash, melted mudbricks, and melted pottery. It was obvious that an intense firestorm had destroyed this city long ago. This dark band came to be called the destruction layer.

No one was exactly sure what had happened, but that layer wasn’t caused by a volcano, an earthquake, or warfare. None of those are capable of melting metal, mudbricks, and pottery.

To figure out what could, our group used the Online Impact Calculator to model scenarios that fit the evidence. Built by impact experts, this calculator allows researchers to estimate the many details of a cosmic impact event based on known impact events and nuclear detonations.

It appears that the culprit at Tall el-Hammam was a small asteroid similar to the one that knocked down 80 million trees in Tunguska, Russia, in 1908. It would have been a much smaller version of the giant miles-wide rock that pushed the dinosaurs into extinction 65 million ago.

We had a likely culprit. Now we needed proof of what happened that day at Tall el-Hammam.

FINDING “DIAMONDS” IN THE DIRT

Our research revealed a remarkably broad array of evidence.

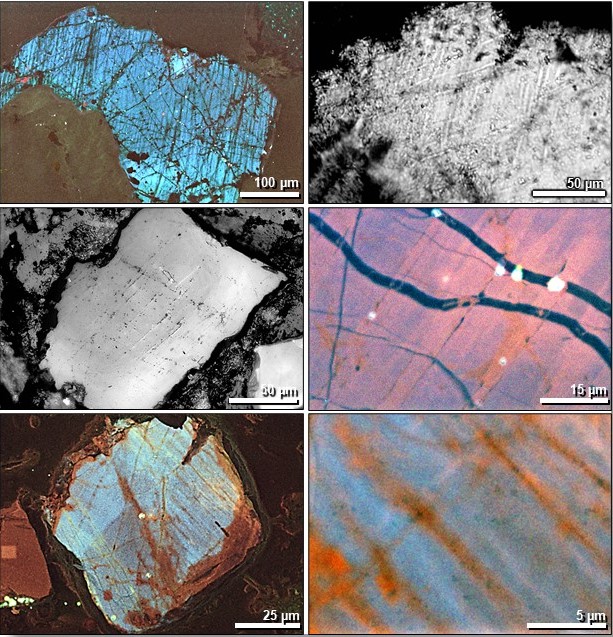

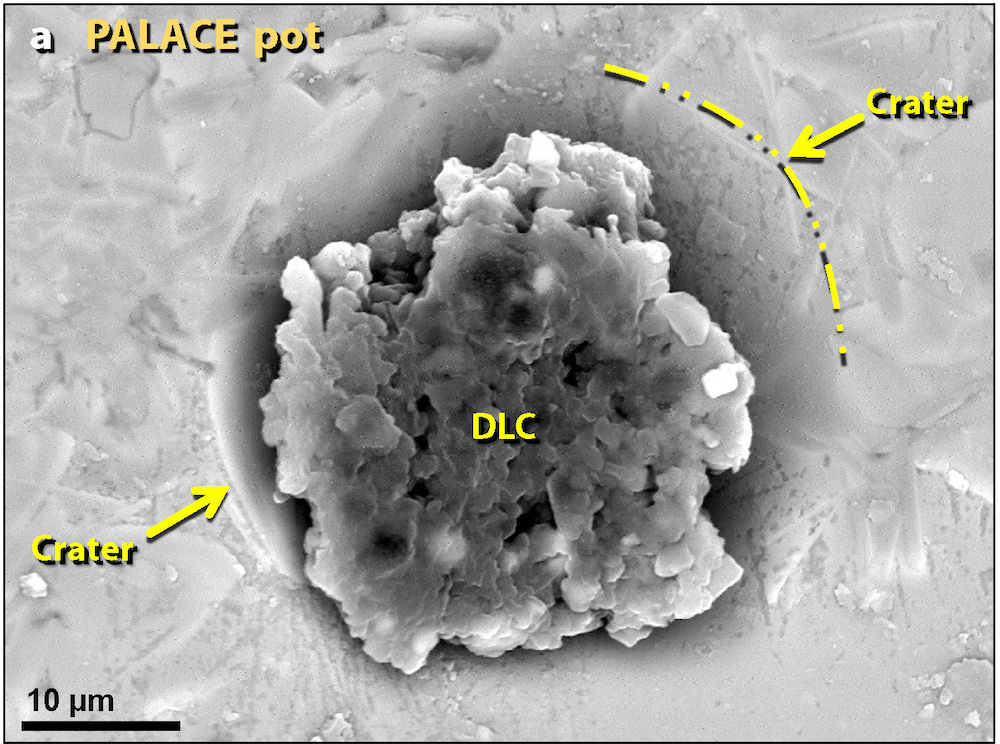

At the site, there are finely fractured sand grains called shocked quartz that only form at 725,000 pounds per square inch of pressure—imagine six 68-ton Abrams military tanks stacked on your thumb.

The destruction layer also contains tiny diamonoids that, as the name indicates, are as hard as diamonds. Each one is smaller than a flu virus. It appears that wood and plants in the area were instantly turned into this diamond-like material by the fireball’s high pressures and temperatures.

Experiments with laboratory furnaces showed that the bubbled pottery and mudbricks at Tall el-Hammam liquefied at temperatures above 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit. That’s hot enough to melt an automobile within minutes.

The destruction layer also contains tiny balls of melted material smaller than airborne dust particles. Called spherules, they are made of vaporized iron and sand that melted at about 2,900 degrees Fahrenheit.

In addition, the surfaces of the pottery and meltglass are speckled with tiny melted metallic grains, including iridium with a melting point of 4,435 degrees Fahrenheit, platinum that melts at 3,215 degrees Fahrenheit, and zirconium silicate at 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit.

Together, all this evidence shows that temperatures in the city rose higher than those of volcanoes, warfare, and normal city fires. The only natural process left is a cosmic impact.

The same evidence is found at known impact sites such as Tunguska and the Chicxulub crater, which was created by the asteroid that triggered the dinosaur extinction.

One remaining puzzle is why the city and over 100 other area settlements were abandoned for several centuries after this devastation. It may be that high levels of salt deposited during the impact event made it impossible to grow crops. We’re not certain yet, but we think the explosion may have vaporized or splashed toxic levels of Dead Sea salt water across the valley. Without crops, no one could live in the valley for up to 600 years, until the minimal rainfall in this desert-like climate washed the salt out of the fields.

WAS THERE A SURVIVING EYEWITNESS TO THE BLAST?

It’s possible that an oral description of the city’s destruction may have been handed down for generations until it was recorded as the story of Biblical Sodom. The Bible describes the devastation of an urban center near the Dead Sea—stones and fire fell from the sky, more than one city was destroyed, thick smoke rose from the fires, and city inhabitants were killed.

Could this be an ancient eyewitness account? If so, the destruction of Tall el-Hammam may be the second-oldest destruction of a human settlement by a cosmic impact event, after the village of Abu Hureyra in Syria about 12,800 years ago. Importantly, it may be the first written record of such a catastrophic event.

The scary thing is it almost certainly won’t be the last time a human city meets this fate.

Tunguska-sized airbursts, such as the one that occurred at Tall el-Hammam, can devastate entire cities and regions, and they pose a severe modern-day hazard. As of September, there are more than 26,000 known near-Earth asteroids and 100 short-period near-Earth comets. One will inevitably crash into the Earth. Millions more remain undetected, and some may be headed toward the Earth now.

Unless orbiting or ground-based telescopes detect these rogue objects, the world may have no warning, just like the people of Tall el-Hammam.

This article was co-authored by research collaborators archaeologist Phil Silvia, geophysicist Allen West, geologist Ted Bunch, and space physicist Malcolm LeCompte.

Editors’ Note: For a critical view of this research, read the latest: “When Biblically Inspired Pseudoscience and Clickbait Cause Looting.”