Archaeology’s Role in Finding Missing Indigenous Children in Canada

On the evening of May 27, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced that the unmarked graves of more than 200 children had been found on the former grounds of the Kamloops Indian Residential School. The story quickly dominated Canadian news media and drew attention beyond our national borders.

After the initial Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc announcement, news followed of similar Indigenous community–led investigations taking place across the country. As of today, more than 1,000 missing children and unmarked graves have been reported in the media.

The implications of these findings are clear. The aggressively assimilationist state- and church-run school system, which held more than 150,000 Indigenous students in more than 130 schools for well over a century, was responsible for the deaths of a staggering number of children.

The published numbers have shocked many Canadians but have not come as a surprise to Indigenous communities, who have long spoken about the horrific conditions experienced at residential schools and the thousands of children who died while there. For years, survivors and affected communities have been working to seek justice, share knowledge, and care for their missing children.

As RoseAnne Archibald, National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, said at a press conference: “These are not ‘discoveries,’ these are ‘recoveries.’”

Having worked as archaeologists for years with Indigenous communities in Canada to uncover such unmarked graves, we also already knew, intimately and powerfully, about these deaths. Eric has been working with the Penelakut Tribe on the Kuper Island Industrial School since 2018. Katherine has been working with the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation on the Brandon Indian Residential School in Manitoba since 2012.

We have located unmarked graves at both schools.

From 2008–2015, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) heard accounts from more than 6,750 survivors who shared their stories of the cultural destruction and personal abuse they suffered as students. Survivors gave personal accounts of intergenerational impacts and—in specific and horrific terms—how many of their relatives and classmates had died while in the schools’ care.

The TRC confirmed that 3,201 children died while attending residential schools—the full toll is likely higher. The majority of these children are designated as “missing”: buried in graves that have become unknown or were never marked in the first place; buried clandestinely; having died at hospitals, sanatoriums, or other institutions, or while in transport or in trying to escape. Records of death were kept poorly or not at all. Parents and families of the children were often not informed of their child’s death or place of burial.

The TRC’s final report made 94 calls to action. Many of them remain unfulfilled—particularly 71–76, which call for a national response to locate and care for these missing children.

The recent news has abruptly awakened our country to this shameful reality, and another: that non-Indigenous Canadians haven’t learned enough. The TRC’s multivolume report and the many thousands of survivors who have spoken their truth and shared their experiences have not been properly listened to.

Both the scale of the tragedy and individual accounts of abuse were already on record. If the world had been paying closer attention, if non-Indigenous Canadians had done more to actively acknowledge this appalling part of our history, people would not have been so shocked by the Kamloops announcement nor surprised that so many other Indigenous communities across the country came forward to speak of their own similar, devastating losses and tragedies experienced over many generations.

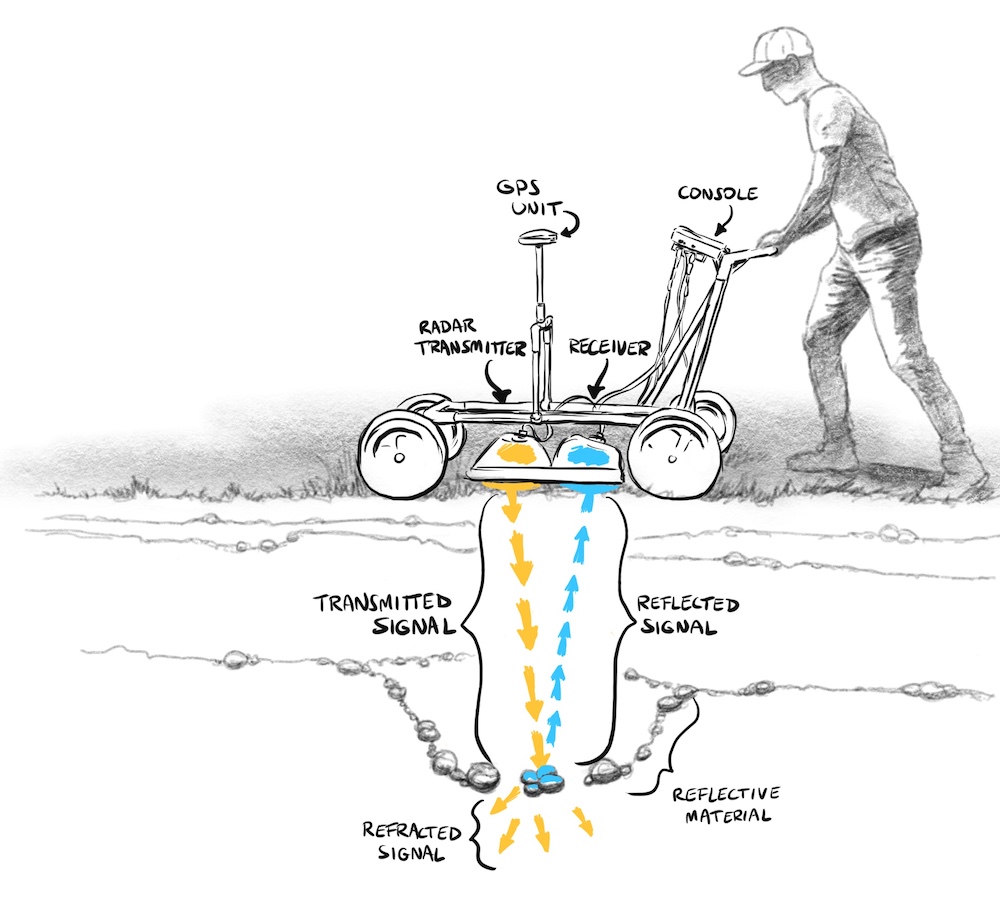

To help find these graves, archaeologists (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous) use ground-penetrating radar (GPR) technology. As a GPR device is moved across the landscape, it produces electromagnetic waves and records the signals’ return, allowing us to visualize what’s below the ground’s surface. GPR is useful for finding grave shafts, where ground has been disturbed, but seldom “sees” the contents of the burial itself.

GPR’s primary strength is in identifying areas of concern on the landscape. This enables communities to better care for the missing children—whether that be through spiritual care and memorialization, protection from disturbance, or the process of identifying and possibly reburying individual children.

While utilizing GPR in the search for unmarked graves presents significant methodological challenges, we have found even greater challenge lies in its responsible use. Archaeological surveys of residential school landscapes are necessarily conducted within complex social landscapes. Archaeology can serve a role in the broader Indigenous community process of finding and caring for missing children. But this work must be done cautiously and be directed by caretaker communities, with the well-being of their people put first.

View this photo essay from the SAPIENS archives: “Native American Children’s Historic Forced Assimilation.”

We each work under the guidance of leaders and Elders in a community that has responsibility for the care and memorialization of missing children. Community leaders set the pace of our work and teach us cultural competency and how to ensure spiritual safety. This learning, and the archaeological work that happens in tandem with it, takes years—even decades.

As Sioux Valley Dakota Nation Councillor Elton Taylor told Katherine, “It’s possible that my children will still be doing this work when they are my age.”

At the Brandon Indian Residential School, the team that Katherine works with has found three sites of interest and as many as 104 potential unmarked graves. However, only 78 death records have been found in the archives.

Work on the grounds of the Kuper Island Industrial School began in 2014. The initial TRC investigation stated that at least 167 students died over the school’s 85-year existence. Yet archival records of place-of-burial were found for only four children.

We each use GPR and archival research, and work with survivor accounts to locate these missing children. Our investigations are ongoing, and each of us is working in close collaboration with community leaders and Elders to carefully determine appropriate next steps.

We have both grappled with the weight of this work—the emotional toll, and, especially, the responsibility to do it properly. We continue the work because we are asked to by our Indigenous partners and because we believe archaeology has a unique contribution to make in the search for missing children.

Communities undertaking this work face significant challenges.

Some of these are emotional and spiritual—there is an ever-present risk of retraumatizing those who have already been subjected to the violence of the residential school system. Others are more practical: Communities add to their already significant administrative burdens as they attempt to coordinate with allies in various professions and with churches and governmental agencies that function as gatekeepers, controlling access to archival evidence, funding, and other resources.

For communities and allies who were already engaged in residential school community–based work, the scattershot of pledges and financial support from governments and churches following the Kamloops news was welcome but provoked uncertainty.

We have both grappled with the weight of this work—the emotional toll, and, especially, the responsibility to do it properly.

Throughout this summer, Indigenous communities with experience in this work took the lead. In mid-July, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc addressed the public about their ongoing work at the Kamloops residential school.

The Sioux Valley Dakota Nation hosted two gatherings with Grand Chief Jerry Daniels of the Southern Chiefs’ Organization and Grand Chief Garrison Settee of the Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak. Speakers called on churches and the state to take full responsibility and recognize the residential schools as an act of genocide. “Without truth, there can be no reconciliation,” said Grand Chief Settee.

On British Columbia Day on August 2, the Penelakut Tribe organized a march for the children in the city of Chemainus that was attended by thousands from neighboring Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous Canadians. Penelakut Chief Joan Brown told the crowd: “Today we are walking for the children who didn’t have the chance to walk with us.”

These communities are developing methods and protocols, directing allies, articulating goals and needs, and balancing urgency with caution. They are calling on the non-Indigenous people of Canada to acknowledge the reality of their missing children and to stand as allies, and they are calling on our governments and churches to live up to their obligations, to speak their truths, and to follow through on the TRC’s calls to action.

The summer of 2021 has been a period of learning for non-Indigenous Canadians, as national and international attention has brought a measure of awareness about the scope of damages caused by Canada’s Indian Residential School system. All this has received concerted attention for the first time since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded in 2015.

Non-Indigenous Canadians became more aware of how little has been done by our governments—and just how much more there remains to do—to respond to the TRC’s calls to action. Today, over five years after the report’s release, only 13 of the 94 calls have been fully implemented; 20 still have no plan or funding in place.

Journalists have reported that the Roman Catholic Church has neither fully shared archival information that could otherwise aid the search for missing children nor honored their pledge to pay reparations. We are also reminded that the TRC, while accomplishing much, was hobbled from the outset, not granted subpoena powers nor able to compel perpetrators to engage with the commission process.

As archaeologists, we are reminded of the uncomfortable fact that the evidence we produce garners more attention from the Canadian media and public than does the knowledge and histories of Indigenous peoples. It is disheartening that this long-overdue national conversation and reckoning has been triggered by the disproportionate evidentiary weight that “professional” investigation and physical evidence carries.

This power imbalance must be corrected. Survivors must be heard.

In every community where we and many of our colleagues have worked, Elders tell us the same thing: “We have always known this—it happened to me and to all my family.” The stories of survivors and the complex work of Indigenous communities to seek justice and to find and care for their missing children must receive the attention and support they are due.

Locating and identifying the missing children’s graves will be a long and complicated process. Indigenous communities have taken on the work of coordinating with allies in various professions, with agencies who control access to archival evidence and other resources, and with neighboring communities whose children were taken to the same schools. They pursue truths and reconciliation with a determination that churches and governments have so far failed to match.

It is of paramount importance that Indigenous communities do not shoulder this alone. Non-Indigenous allies have a responsibility to ensure that current momentum, spurred by the revelations of this summer, is not lost.

For communities and allies who were already engaged in Indian Residential School community–based work, this past decade has been challenging without a national strategy in place. Despite this, communities such as the Penelakut Tribe, the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, and many others have begun this difficult work and are demonstrating how to do it well, forging a path that others might follow.