How Many People Lived in the Angkor Empire?

This article was originally published at The Conversation and has been republished under Creative Commons.

How big were the world’s ancient cities? At its height, the world’s first city of Uruk may have had about 40,000 people about 5,000 years ago. In the medieval period, London may have had a population of about a quarter of a million people, growing to approximately 600,000 by the early 17th century.

One of the world’s largest ancient cities lies in the jungles of Southeast Asia in the greater Angkor region located in contemporary Cambodia. This medieval site was home to the Angkor or Khmer Empire from the ninth to the 15th centuries. You might be familiar with the famous Angkorian temple, Angkor Wat, one of the largest religious monuments in the world.

But most people don’t realize that Angkor Wat is just one of more than a thousand temples in the greater Angkor region. Our research suggests that this settlement may have been home to between 700,000 and 900,000 people at its height in the 13th century. This means that the population of Angkor was roughly comparable to the almost 1 million people who lived in ancient Rome at its height.

Here’s how our interdisciplinary team came up with our population estimate for Angkor and how it grew over time.

Mapping medieval structures in Angkor

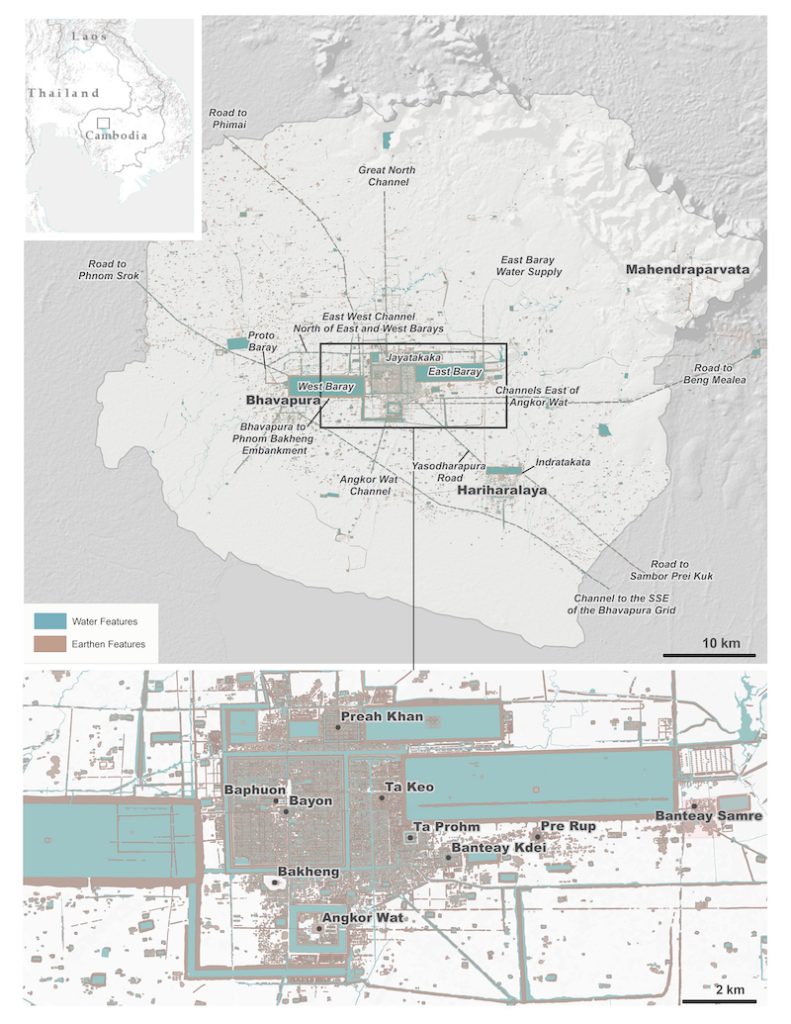

Over the last 30 years, archaeologists working in collaboration with Cambodia’s APSARA Authority have been exploring the jungles and rice fields of Cambodia, documenting thousands of medieval features that remain inscribed on the landscape. This work has included digging traditional excavation sites, surveying the landscape from the back of dirt bikes, and scanning satellite imagery for traces of these ancient features.

Our knowledge of the region entered a new era in 2012 when researchers from the Khmer Archaeological Lidar Consortium organized a mission of airborne-laser scanning across this World Heritage site. Called lidar, this technology was able to do in a few days of scanning and data processing what had previously taken archaeologists months, if not years, of work: see through dense vegetation to accurately map the ground surface of Angkor.

With this lidar data, researchers were able to map tens of thousands of archaeological features at Angkor. Because Angkorian people, like many Cambodians today, built their houses out of organic materials and on wooden posts, these structures are long gone and not visible on the landscape. But lidar revealed a complex urban landscape complete with city blocks consisting of the mounds where people built their houses and small ponds located next to them.

This work has created one of the most comprehensive maps of a sprawling medieval city in the world, leading us to ask: How did the city develop over time, and how many people lived here?

Deducing who used these structures and how

Our new research published in the journal Science Advances created a comprehensive database that unites 2012 lidar mapping work with a massive archaeological dataset acquired by an international team of scholars over the last 30 years. Our goal was to combine all available data into one framework so we could understand which buildings had existed at various points in time and then ascribe the right number of people to each structure in order to come up with overall population estimates.

The part of Angkor’s landscape that most people are familiar with is what we call the civic-ceremonial center—it includes major stone temples such as Angkor Wat and the Bayon. These areas are similar to what you might consider “downtown.” We think many of the people living here supported the operation of the temples and state government as craft specialists, artisans, dancers, priests, or teachers. These people would have relied on rice surplus generated by farmers, although recent work suggests they may have also tended small house gardens.

People who inhabited the occupation mounds and rice fields in the surrounding Angkor metropolitan area had a different kind of lifestyle. These people were predominantly farmers and would have spent their days planting and harvesting rice.

The third area of occupation was on the embankments of roads and canals. Very little research has been done on the embankments, but some members of our team think that people lived on these features and would have been engaged in trade and commerce.

Placing people on a timeline

Next we wanted to figure out when people were using these structures and if they were living in different areas at different times.

In some cases, we could use inscriptions and changes in the decorative styles of the temples to help date features on the landscape. In other cases, we used machine learning algorithms to sort temples in terms of similarity based on every bit of information we have about them: orientation, size, artifact types, pedestal types, and so on. Then we used the known dates we do have for some temples to predict dates for others based on how close they are to one another on the algorithm’s graph.

Combining the lidar data showing the location of mounds and our database dating features on the landscape, we were able to estimate the growth of the population over time in these areas. But it was tricky and will require some additional work to confirm our model.

Using excavation data from work by the Greater Angkor Project at Angkor Wat, we hypothesize that households in Angkor’s civic-ceremonial center and on the embankments were approximately 6,500 square feet. Ethnographic data suggest that there may have been five people in a household of this size.

Estimating the population in the rice fields surrounding the civic-ceremonial center, what we call the Angkor metropolitan area, was more difficult as few occupation mounds remain. However, dispersed among rice fields were temples, which were likely the social basis for these communities. These areas are similar to farming communities in the U.S., where people are primarily involved with agriculture but congregate at their places of worship. Ethnographic data suggests each of these small temples may have served about 100 families, or 500 people.

In the early stages of Angkor’s growth, we found fairly equal populations in the civic-ceremonial center and Angkor metropolitan area, but then the population in the countryside exploded as the city began to grow. In contrast, the civic-ceremonial center’s population grew more slowly until the late 12th century. Our ongoing research explores how and why these changes took place. Densities also increased in both the Angkor metropolitan area and the civic-ceremonial center, which provides clues about how population levels and land-use patterns evolved over the city’s life span.

Cities gone for centuries hold lessons for today

By viewing this data in aggregate, we were able to put the pieces of the puzzle together and reconstruct the past landscapes of Angkor like never before. Combined, we start to get a pretty clear idea of how the city developed, including who was living where and when, as well as how that affected the development of the city.

Our research has broad implications that reach far beyond how many people lived in the greater Angkor region over a thousand years ago. ![]() Researchers can apply this precise information about how a city grew, how many people lived there, where they lived, and what they did to the challenges of contemporary cities.

Researchers can apply this precise information about how a city grew, how many people lived there, where they lived, and what they did to the challenges of contemporary cities.

What makes them resilient to climatic, social, and political challenges? How do you support this many people living in close quarters? What happens when people congregate in a small space and the populations get larger and larger over time? Are there efficiencies of scale? Do cities lead to inequality? Are there universal and mathematical truths that define the relationships between people and cities?

By looking at examples of urbanism from the past, researchers can start to answer some of these questions for the future of today’s cities.