Wrestling With the Culture of Drug Testing in Sports

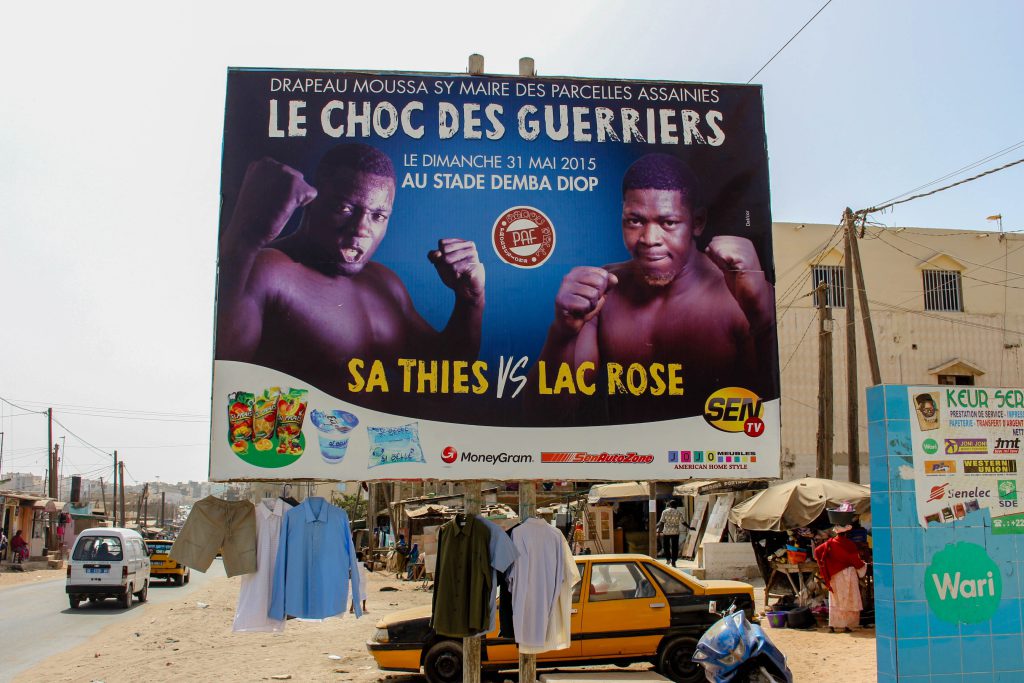

On May 31, 2015, the combat between rising stars Sa Thies and Lac Rose marked the beginning of a new era in Senegalese wrestling. After Sa Thies emerged victorious from their tussle in a sandy ring, both competitors were sent for a drug test, a brand new requirement for the sport. But Sa Thies was unable to comply because the traditional amulets he wore, he claimed, prevented him from urinating. International standards against doping in sports had only just arrived on the Senegalese wrestling scene, and controversy set in from the start.

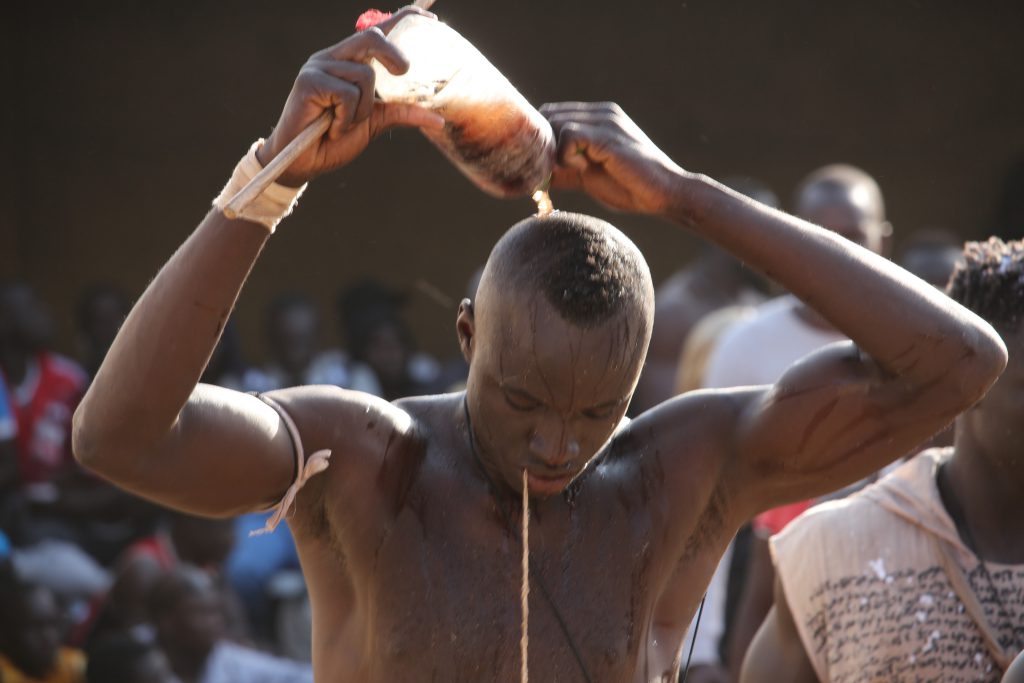

In the West African nation of Senegal, lutte avec frappe (or “wrestling with punches,” a hybrid of traditional wrestling and bare-knuckle boxing) surpasses football as the most popular sport, capturing the attention of the masses and promising fame and fortune to its stars. Even though it has become intensely commercialized, the sport remains deeply tied to tradition, which is what makes it appealing to many fans. A host of mystical factors are as important to a competitor’s success as physical strength and technical prowess. Spiritualists (marabouts) dispense prayers. Animals are sacrificed. In preparation for a fight, participants have amulets (gris gris)—typically small leather pouches with Quranic verses tucked inside—strapped to their arms, legs, and chests. Endless bottles of sacred liquids (saafara), prepared at great cost, are poured over the wrestlers. Tunics adorned with scripture are put on. Magical canes and animal horns are brandished in the opponent’s direction. Some wrestlers even release pigeons into the middle of the ring before a fight. These are just some of the magico-religious preparations (xarfaxufa) that precede combat—even more go on behind the scenes, out of the public eye.

So it was a strange meeting of worlds when modern, international anti-doping rules were brought to bear on the sport in 2015. I was in the middle of a year of ethnographic fieldwork at the time in Senegal’s capital, Dakar, where I was studying wrestling and football in the region, and so I saw the debate among wrestlers, administrators, fans, and the media as they struggled to reconcile these new rules with their traditions. [1] [1] Editors’ note: The research reported herein was conducted with funding from the European Research Council under Grant Agreement 295769 for a project entitled “Globalization, Sport, and the Precarity of Masculinity” (GLOBALSPORT). “We need to stop trying to modernize the wrestling arena too much,” said Sa Thies in a local media interview. “We don’t need doping tests in our sport. Wrestling isn’t a white man’s business.”

Not everyone takes the same view as Sa Thies. In recent years, the world of Senegalese wrestling widely and publicly agreed that substance regulation of some kind was necessary for their national sport—if only to protect the health of athletes, many of whom are poorly informed about the potential risks of doping. The consumption of anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing substances was an open secret, even among members of the Comité Nationale de Gestion de la Lutte (CNGL), the national steering committee of Senegalese wrestling. Many high-profile wrestlers returned from training spells in the United States and elsewhere with radically altered physiques that seemed unlikely to have been achieved through training alone.

It was in this climate that the CNGL decided to bring the rules established by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) to the world of Senegalese wrestling. WADA was founded in 1999 as an international, independent agency made up of, and paid for by, sports organizations and governments around the world. In 2004, they came up with the World Anti-Doping Code (commonly called the Code), to synthesize anti-doping policies. The Code regulates which substances should not be allowed, how they might be detected, what exceptions might be permitted for medical reasons, and more. It has become the gold standard for many sporting organizations, including the International Olympic Committee.

In 2011, a Senegalese governmental body called the Organisation Nationale Antidopage Sportif was formed to implement WADA’s rules. In 2015, they rolled out drug testing in time for Sa Thies’ emphatic victory. Lac Rose, the defeated contender, was able to provide the nearly 1 quart of urine required. In contrast, Sa Thies could only deliver about half that amount, and he left without fulfilling his anti-doping obligations.

A member of Sa Thies’ entourage pointed out that it is difficult to urinate after combat. There could be a biomedical explanation for that: Dehydration might prevent an athlete from providing a full sample. But the wrestler’s companion wasn’t talking about biology; he explained Sa Thies’ inability to urinate in mystical-spiritual terms. “He did his best, but he was bothered by the gris gris [amulets] contained in his nguimb [loincloth],” he told the media. “There are certain things which his mother alone is authorized to remove.”

Senegalese wrestling is deeply ingrained in a magico-religious cosmology that extends far beyond the boundaries of sport. During my fieldwork, wrestlers would often explain their defeat in reference to mystical practices. One interviewee memorably told me that his opponent made himself invisible in order to achieve victory. Other stories I heard alleged that opponents increased their size, made their bodies impervious to punches, or paralyzed or weakened their rivals in nonphysical ways.

This may sound odd to those unfamiliar with Senegalese wrestling, but it isn’t all that different from some aspects of other sports—take the pageantry of World Wrestling Entertainment Inc. (formerly the World Wrestling Federation) or the lucky underwear worn by some baseball players as examples. Many sports around the world have their own particular cultural landscape.

The Code, too, is embedded in its own cultural world, one in which objective, scientific facts are often seen as the only truth. This can be problematic. Observers have noted how the sports world tends to reduce athletes to a set of biomedical data, treating them as a subclass of citizens with little right to privacy or self-identification. Take, for example, the famous case of Caster Semenya, a South African runner who had to undergo sex verification tests to confirm she was female after her impressive performances and so-called masculine appearance cast suspicion on her gender. The testing was “both sexist and racist,” according to a human rights complaint filed by South Africa with the United Nations.

“We don’t need doping tests in our sport. Wrestling isn’t a white man’s business.”

The Western medical community’s viewpoint often comes into conflict with other worldviews. Though Semenya self-identified, lived, and competed as a woman, the apparently objective quality of regulatory testing gave the medical world a kind of undue authority over her identity. Those who strictly adhere to biomedical ideologies have a very fixed way of looking at the world that does not always accommodate differences—whether variations in hormone levels or diverse belief systems.

Facing the possibility of a three-year ban, Sa Thies provided the necessary urine sample over the next few days (the Senegalese regulatory authority allowed for the delay) and tested negative—as have all wrestlers since testing was introduced to the sport. Some experts have suggested that the negative tests don’t necessarily mean the athletes are clean but that the herbs, potions, and traditional medicines they are taking might be somehow interfering with the doping tests.

As Sa Thies said, Senegalese wrestling isn’t a white man’s sport (although Juan Francisco Espino, a white Spanish wrestler widely known as “Juan,” competes), but the community itself has decided that drug abuse is a problem that needs to be solved. Rigorous biomedical testing seems the best way to determine if drugs are in someone’s system; the WADA rules are appropriate for that. Yet the regulatory bodies governing sports should remember that the biomedical framework is not the only one that leads to the truth, the only way of defining an athlete, or the only guide for how to do things. Other worldviews matter too.