The Dangers of Birth in Tanzania

Women in sub–Saharan Africa have a 1 in 36 lifetime chance of dying from pregnancy-related causes. That’s down 45 percent since 1990, due largely to advocacy campaigns and public-health initiatives urging pregnant women to give birth at village dispensaries, health centers, and hospitals—rather than at home. But the risks are still numerous, and this part of the world bears the largest burden of maternal deaths globally, by far.

In Tanzania, the government and numerous global health agencies are doing what they can to lower the death rate further. But they have a complex web of challenges to overcome. A recently published series on global maternal health in The Lancet highlights the difficulty. As some of the authors argue, even though spreadsheet statistics may indicate improvement, the situation on the ground is far less encouraging, and the one-size-fits-all approach laid out by many global nonprofits overlooks important local realities.

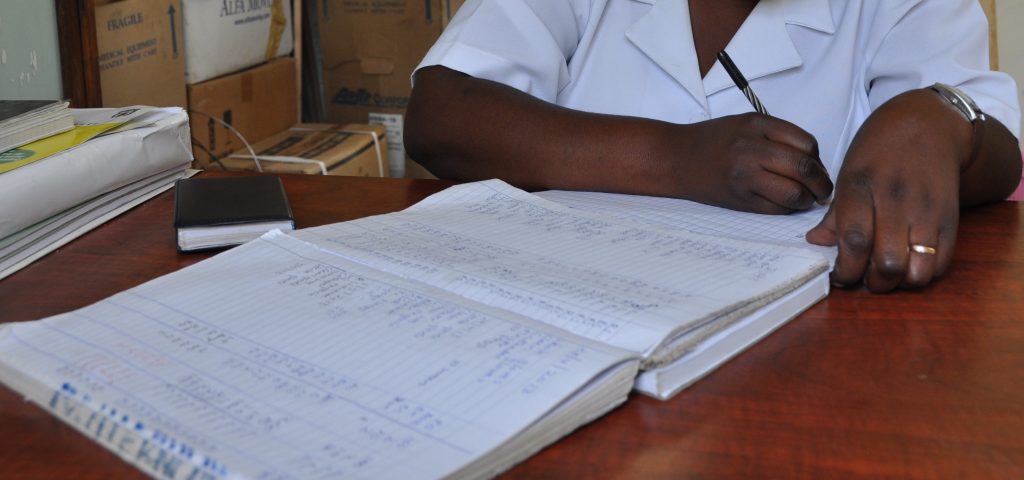

One such reality is that health care in Tanzania is underfunded and understaffed, and those providers that the country does have are stretched thin. I spent nearly two years conducting research on the maternity ward of the Sumbawanga Regional Hospital, in the Rukwa region of Tanzania. This hospital provides the highest level of care in the region, and it serves over 1.5 million people in one of Tanzania’s poorest and most geographically isolated areas. Most who live there survive on less than US$1 per day.

During the time I spent at the hospital, over the course of three trips between 2012 and 2015, it became abundantly clear that just getting a pregnant woman to a place of care isn’t enough to keep her and her baby safe. Under-resourced health facilities are as great a barrier to reducing the number of maternal deaths as lack of education and roads.

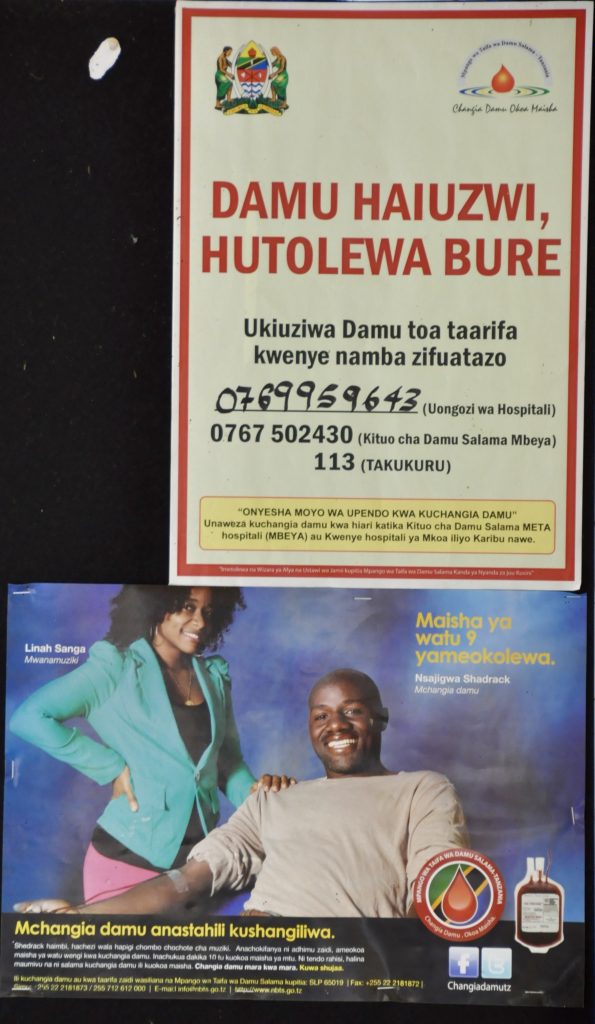

I found that poor working conditions in the hospital are the result of a range of factors, from poor communication and inexperienced leadership to a chronic shortage of funds. Despite a government mandate to provide free care for pregnant women, nurses and doctors sometimes must tell impoverished families to buy drugs, syringes, or catheters from private pharmacies. When hospital personnel fail to inform them that insufficient government funding is the reason they have to purchase their own supplies or medications, patients often suspect that the needed items have been stolen and sold by corrupt health care workers.

It’s a suspicion that has historical merit. In the past, health care providers’ low wages have led them to sell both legally and illegally obtained medical supplies and drugs to desperate patients. While the practice has largely been eradicated, many people remain wounded by memories of times when they lacked access to supplies and medicines that they were entitled to as citizens.

Suspicions permeate interactions between patients and nurses, resulting in mistrust and social tension. Providers themselves are hampered by low salaries, delayed promotions, a lack of transparency, and poor communication with administrators. This culminates in a difficult work environment—one that often causes tension between staff and patients and results in provider burnout. In the midst of such turmoil, women and their newborns too often slip through the cracks.