For Rio’s Poorest Citizens, Police and Gang Violence Reign

On the night of June 24, 2013, the streets of the Complexo da Maré (Maré Complex), a district in northern Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, were full of bustle: food vendors in brightly lit stalls, commuters returning from late work shifts, and neighbors talking and laughing in front of tightly packed houses. Then a police squad arrived in cars and tanks, and heavily armed policemen started shooting, sending residents fleeing for cover. Maré was home to a drug-trafficking gang and the police officers were out for blood—one of their own had died at the hands of the gang the previous night.

Police, in vehicles and on foot, fired at gang members. Gang members shot back. The gunfire stopped and started throughout the night. By dawn, at least eight gang members and one bystander lay dead. It was not the first time—nor would it be the last—that state forces gunned down poor, black Brazilians in urban peripheries.

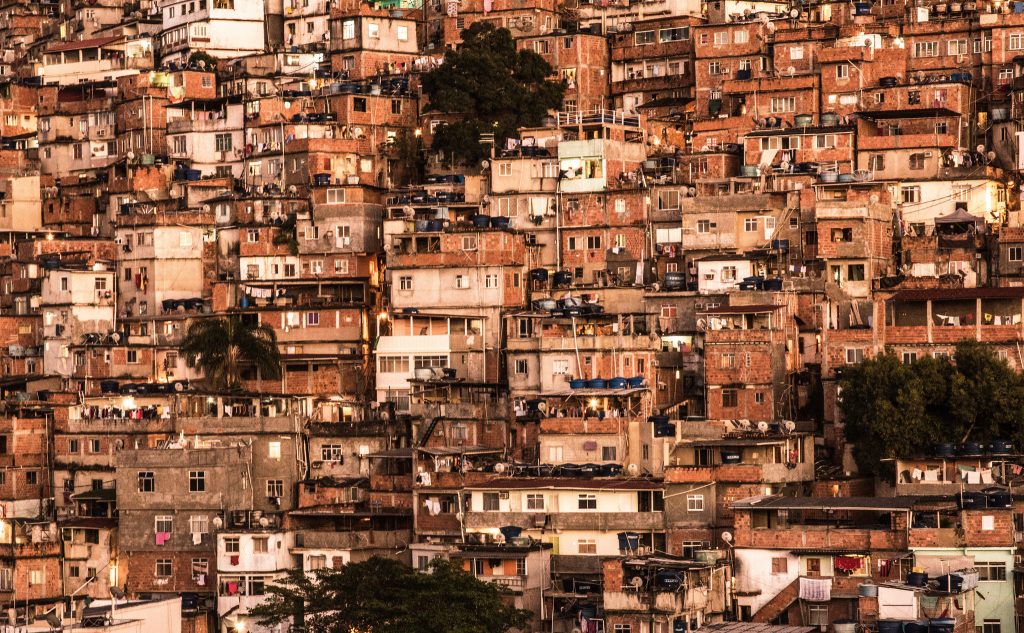

The city of Rio de Janeiro is located in the Brazilian state of the same name. The city’s working classes have built their own neighborhoods over the past several generations. These impoverished favelas are home to around 1.5 million people—nearly a quarter of the city’s population. Maré is one of Rio’s largest favela “complexes,” vast districts of favela neighborhoods. Walk into its teeming, narrow streets on an average day and you are assaulted by the pungent smell of raw sewage and a wave of sound—thumping funk music, revving motorcycles, the din of chattering voices. Tangles of pirated electricity wires hang overhead. Originally informal settlements, the favelas are now official city neighborhoods, but they’re marked by inadequate public services and heavy gang and police violence.

On July 2, a week after the shootout, a group of civic organizers from Maré led what they called an “ecumenical action”—a rally in which people of all faiths gathered in memory of the dead and in protest of ongoing police abuses. As many as 5,000 people from within and outside of Maré turned up to march along Avenida Brasil, a major city thoroughfare bordering the complex. Marchers carried banners that read, “Estado que mata, nunca mais” (No more state murder). A performance piece featured actors splayed out in the street, motionless. They were separated from the crowd of onlookers by a circle of red ribbon. One of the bodies represented the murdered policeman whose death had prompted the shootout.

I have spent several years doing ethnographic research with the rally’s organizers, many of whom are affiliated with the local nonprofit Redes da Maré (Maré Network), and I’ve come to see their demonstration as part of a larger vision. It was more than a protest. Yes, they were angry, and they despised the police who consistently mistreated them. Yes, they helped raise a collective voice against police violence. But the march also emphasized the organizers’ conviction that the best way to prompt true, lasting change was to engage the police directly. Including a representation of the policeman’s body in their memorial performance symbolized the dialogue they wanted to have with law enforcement about how to move forward.

Protests against police abuses in low-income, black neighborhoods have become increasingly common—in the U.S., the Black Lives Matter movement has brought the issue into the national spotlight. These bold voices are crucial to addressing the problem. It is far less common, however, to hear from the abused what their vision is for a path to improvement. In Rio, there’s good reason for this: Drug-trafficking gangs have a great deal of power in favelas and threaten anyone who speaks out. But against all odds, Redes da Maré activists and their collaborators are working to move beyond the seemingly unshakable patterns of gang violence and police abuse. And their vision can inform the way all of us think about how to move toward long-term solutions.

In the city of Rio, the public’s intensifying fear of crime—itself a symptom of extreme social inequalities—has caused residents throughout the city to push the state government for increased safety. This in turn has led to an increasingly militarized state response that is largely relegated to the poorer neighborhoods.

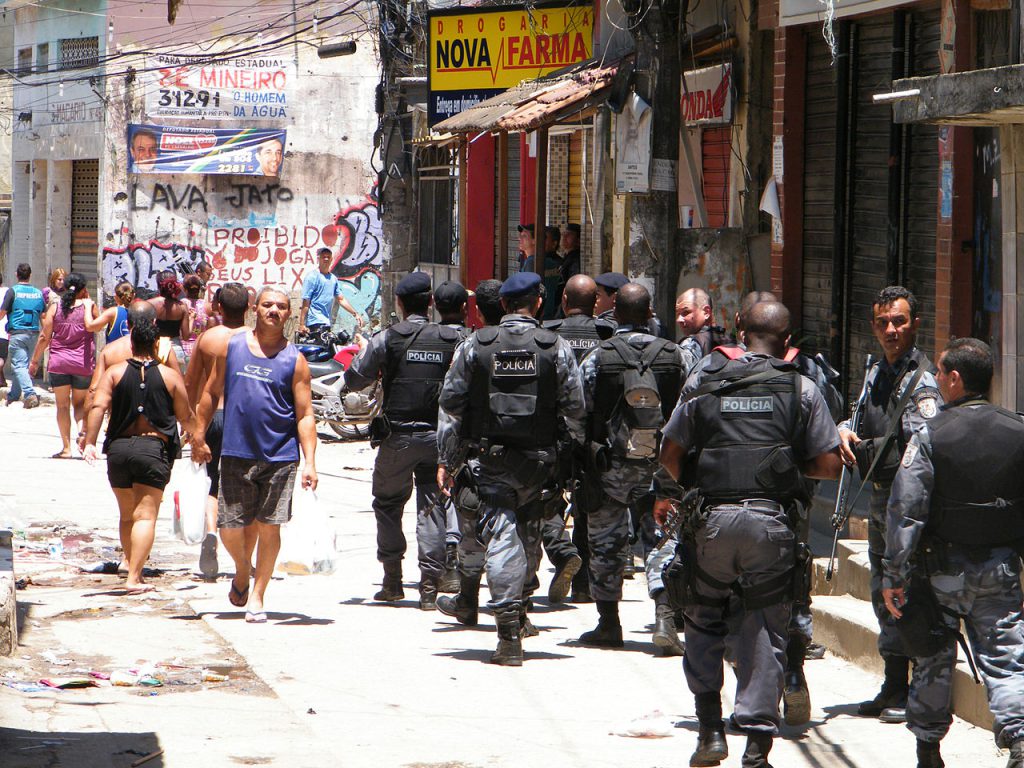

Police in the state of Rio de Janeiro are waging a literal war on drug-trafficking gangs in favelas. Like soldiers in enemy territory, they enter the favelas in armored tanks, shoot at people in the streets, attempt to capture or kill gang members, and then retreat. Often, in lieu of public trials, police kill those they decide are guilty of drug trafficking. And they throw a very wide net, treating every favela resident as a potential suspect: They detain and frisk people in public, force their way into private homes, and destroy personal property in search of weapons and drugs. According to the human rights group Amnesty International, between 2005 and 2014, state police in the city of Rio de Janeiro killed 5,132 residents, most of whom were young black men. (Compare this to Chicago, Illinois, the highest-ranking U.S. city in fatal police shootings, where police killed 70 people between 2010 and 2014, as shown by the nonprofit Better Government Association.)

The majority of the city’s more than 1,000 favelas are controlled either by drug gangs or by militias, which often have ties to corrupt police and politicians. Whereas militia-dominated favelas see fewer police raids, those controlled by drug gangs are raided regularly, and the gangs fight back: They prevent police from entering their streets via gunfire, roadblocks, and other obstacles. Beginning with the arrival of cocaine in the city in the 1980s, gangs consolidated their power and adopted a range of state-like roles in favelas. In place of state control, the gangs developed informal systems of law and order.

Today, gangs provide some measure of security in favelas: They resolve disputed land claims and other conflicts, dole out punishment for crimes such as theft, and provide cooking gas and other goods to the neediest. But they can also be arbitrary and brutal. Favela residents witness gruesome violence among traffickers and live in fear that false rumors could lead to their own beating, banishment, or death. Battles among different gang factions regularly send bullets ripping through the densely populated favela streets.

In late 2008, the Rio de Janeiro state government rolled out a program called Unidade de Polícia Pacificadora (Police Pacification Units). It was an attempt to both diminish gang control of territories and reform the state’s aggressive police force, and it seemed to work—at least initially. In the following few years, several favelas shifted from gang to police control. Gang members were killed, arrested, or forced to flee, and gun violence in those favelas decreased dramatically. For the first time in a long while, many people in Rio were hopeful that the city’s crime problems might be addressed. And inside favelas, policing looked completely different. Instead of entering favela streets with their guns blazing, police were stationed there permanently and conducted regular foot patrols. Though favela residents throughout the city were skeptical of the new policing program, they simultaneously felt a hesitant relief at the prospect of being out from under gang control.

But reaching that point required a huge investment. First, state troops conducted massive assaults, often rolling through favelas in tanks borrowed from the military, to wrest territorial control from the gangs. Then, the Police Pacification Units arrived, which, in theory, aimed to work with residents to reduce crime and promote public safety. As of August 2016, the state has introduced pacification in 264 favela territories. Security forces initiated the process in the Complexo da Maré in April 2014, but due to budget cuts, the state never installed pacification units.

I conducted extensive field research between 2012 and 2014, living for a year in a favela neighboring Maré. I was there at a unique moment: Given recent pacification successes in other favelas at the time, Maré residents were anticipating the new policing program in their own neighborhoods—with trepidation but also with a sense that their situation might finally improve.

Several days after the peace rally in July 2013, I attended a follow-up meeting at which Redes da Maré organizers were cautiously celebratory. Despite having drawn necessary attention to their cause, they knew it was just the beginning. “I’m more concerned with what comes next,” said Edson Diniz, a co-director of the nonprofit. He was soft-spoken but adamant. “We want a police force that secures the rights of all citizens, starting with those in Maré.” He and others envisioned a collaborative relationship with police in which they worked together to create a system of law and order that did not discriminate.

For favela residents, voicing any opinion about the topic was risky. If they denounced police abuses, militias with ties to the police might retaliate. If they aligned (or took a position that appeared to align) with police, they risked incurring the wrath of the gangs. Consequently, most favela residents remained silent. Maré’s civic organizers were the courageous exceptions.

A few weeks later, I walked with some Redes da Maré staff and others along a narrow overpass above a clogged, clamorous highway on our way to a police headquarters. We were headed to a meeting bringing police together with nonprofit representatives, neighborhood association presidents, and pastors in preparation for Maré’s pacification. During our walk, one young activist confessed that he felt frightened and physically repulsed. Someone knocked on the imposing metal gates of the compound, and everyone was visibly tense as we waited for the gates to open.

Maré organizers had specific suggestions for the police. They asked that police use targeted intelligence operations against suspected criminals instead of firing guns in the streets, that they forgo the terrorizing armored tanks, and that they stop indiscriminately frisking residents. They called for an ongoing dialogue between citizens and security forces. Favela residents wanted police in their neighborhoods—they just wanted a police force that protected the inhabitants they were ostensibly there to serve. One of the neighborhood association presidents, Osmar Paiva Camelo, visibly shook as he summoned his courage. “We want you to say, ‘Police won’t do harm,’” he told them.

Although the Maré activists were simply trying to move the conversation forward, this meeting, and a handful of others, made them look like pro-pacification police collaborators in the eyes of gangs. That impression proved deadly. In September 2014, just over a year after taking a stand for favela residents, Camelo was murdered. Various rumors circulated, but many residents believed

Between 2005 and 2014, state police in the city of Rio de Janeiro killed 5,132 residents, most of whom were young black men.

traffickers had orchestrated his death, since he’d spoken out in favor of pacification. They interpreted the drug traffickers’ message as: Residents were not to support the police under any circumstances.

Outside the favela, Redes da Maré activists and their collaborators were criticized from all sides. Police accused them of preventing officers from doing their jobs. One police official complained, “I don’t know what the problem is in Maré. Good residents would open their doors.” He insinuated that people with nothing to hide would not mind if police searched their homes. In general, conservatives—including many public officials and mainstream media sources—supported this viewpoint, which was accompanied by calls for tougher, more pervasive policing.

Anti-violence activists throughout the city accused Maré organizers of selling out, saying that more policing—including the pacification program—would only lead to more police violence. Despite many people’s hopes for pacification, these activists felt that the police would merely continue longstanding patterns of abuse. Maré activists were not the only ones trying to find a middle ground in a polarized debate, but they were among the few looking for a more nuanced way through the “more policing” versus “down with police!” impasse.

Meanwhile, Redes da Maré leaders wanted to bring more favela residents into the movement and give them the necessary tools to stand up for themselves against police abuse. Residents needed to know—and exercise—their rights. In November 2012, eight months before the ecumenical action, Redes da Maré and another local group, Observatório de Favelas (Favela Observatory) launched a public-awareness campaign with support from Amnesty International. They informed residents that police are not permitted to detain people for failing to carry identification (which is a frequent practice). And they made sure people knew that police must have a search warrant to enter a home. Informed residents placed stickers on their front doors with a message for police, “We know our rights! Don’t enter this house without following lawful procedure.” Ultimately, while these stickers were unlikely to stop police, they were a symbol of residents’ awareness that they were entitled to different treatment. And this symbolism held the seeds of change.

I left Maré in March 2014. In April, the Brazilian military began what turned into a 14-month occupation of the complex. With federal soldiers instead of state police in their neighborhoods, activists lost the police representatives with whom they’d discussed their vision for the future. Camelo’s murder in September put an abrupt halt to much of the remaining momentum. Terrified for their own safety, other neighborhood association presidents stopped their security-related advocacy. When, in July 2015, the government failed to replace the soldiers with Police Pacification Units, as promised—and instead implemented a superficial display of policing on Avenida Brasil, which borders Maré—all remaining hopes for pacification were dashed.

Even now, as the Olympics get underway, violence in favelas—even the pacified ones—is on the rise. Yet the awareness campaign continues to bear fruit. In a Brazilian newspaper article from April 2016, a Maré resident spoke of a course on citizens’ rights she took at Redes da Maré. When a police officer appeared at her door, she asked him, “Are you going to come in? If you have a search warrant, then feel free. If you don’t, I request that you get one and bring it to me please.” While there are likely more residents who wish they could say such things than residents who actually do, the fact that some might even wish for it indicates a remarkable shift.

Given the risks, Maré organizers have been bold. They are providing an articulate statement on behalf of the urban poor: Physical and verbal abuse by gangs and police are not the only forms of brutality in favelas. The lack of community-oriented policing is its own kind of cruelty.

These marginalized populations want, and deserve, the kind of policing that occurs in Rio’s largely white, middle- and upper-class neighborhoods, where the police forces treat residents with respect. There, while policing may have its problems, it is seen as a public service, the provision of law and order. Favela activists want the same treatment for the city’s poor and black residents. It’s a message relevant the world over. No matter the country or the circumstance, the urban poor are entitled to protection from both gang and police violence. They have a right to policing that helps them feel safe in their own homes and neighborhoods.