Capturing the Art of Imprisonment

Over the span of about four decades, the late Soviet artist Vasily Konovalenko (1929–1989) produced more than 70 wonderful gem-carving sculptures that depict themes and scenes of Russian folk life. Twenty Konovalenko sculptures are on permanent display at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science; another 20 sculptures are on permanent display at the State Gems Museum in Moscow.

One of Konovalenko’s most spectacular pieces is called “Prisoners,” in which two cold men use an ax and a saw to build a shelter at a Siberian labor camp. The snow-and-ice surface on which they work is a single slab of white quartz; the wood being sawed is actually petrified wood carved to look like milled lumber. Their uniforms are made of zebra jasper; their boots are obsidian.

The sculpture is notable for its dull color palette. The prisoners’ black, gray, and white world is broken only by the brown of the wood and the magenta circles on their backs, over their hearts, which provide targets for guards if the men try to run away.

Unlike U.S. prisons, which offer living quarters to prisoners, the gulag under Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin often required newly arrived prisoners to build their own shelters. (The term “gulag” is an acronym for the Soviet Union’s system of prisons and labor camps, Glavnoe upravlenie ispravitel’no-trudovyx lagerej, or the Main Administration for Corrective Labor Camps.)

Also in contrast to U.S. prisons, the men in Konovalenko’s sculpture have weapons—or so it seemed to me at first glance. When I asked Anna Konovalenko, the late artist’s wife, if the prisoners might use the saw and the ax to attack someone, she simply laughed. “What are they going to do?” she asked. “The guards all have guns!” OK, I thought, enough said.

Stalin-era labor camps were full of smart, industrious people, including scientists, artists, politicians, and military men—not the type who would be content to sit around all day. In Konovalenko’s sculpture, the kneeling prisoner (number 0.842) is clearly younger and less jaded than his older partner. For all the harshness of his situation, he seems—for the time being at least—glad to be working on a project, any project, to keep warm and stay productive. His jasper hands grip a petrified-wood saw handle, and his eyes are sapphire. Imperfections in his Beloretsk quartz face indicate the stubble of his beard.

The older, standing prisoner (number 0.857) has an ashen complexion and lusterless eyes. He is perhaps incapable of helping the younger man due to the extreme cold, but he also seems to suffer the physical consequences of a previous lack of activity and now a lack of will. Konovalenko used natural variation in the Beloretsk quartz to make the man appear jaundiced and cold. He carved puffy eyelids to indicate the prisoner’s ill health—note that his right eye is nearly closed.

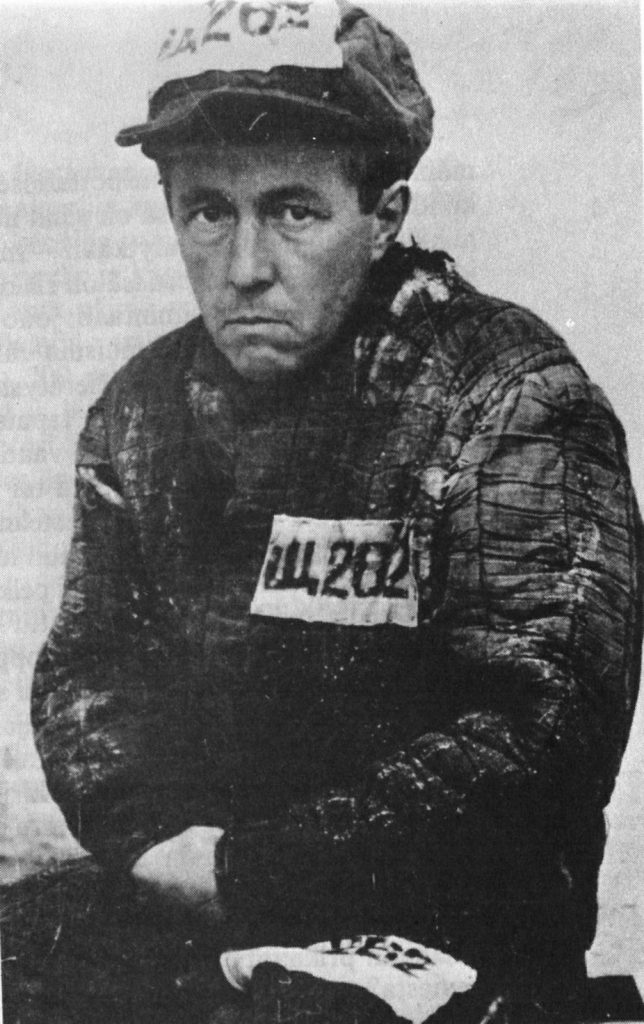

Given the level of detail and the emotional depth of this piece, I wondered if Konovalenko knew anyone who spent time in the gulag. Anna Konovalenko explained to me that “Prisoners” is based on her husband’s reading of the once-banned book The Gulag Archipelago, which was written by the Stalin-era prisoner Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and published in 1973. While conducting archival and library research for my recent book Stories in Stone: The Enchanted Gem Carvings of Vasily Konovalenko, I struggled to find evidence confirming her assertion. On September 5, 2015, while my book was already in production, I finally stumbled upon a remarkable photograph. It’s of Solzhenitsyn and was taken on the day he was released from the gulag in 1953. It bears an astonishing resemblance to prisoner 0.857, including the awkwardly crossed arms, roughly triangular face, and lusterless visage.

As brutal as Solzhenitsyn’s experience of the gulag was, he was able to transform his oppression into writings that exposed the inner failings, violence, and horror of Stalin’s rule. Konovalenko’s sculpture bears another type of witness to imprisonment in the labor camps.

Although the prison system in the U.S. may seem relatively humane by comparison, our country has the highest incarceration rate in the world, thanks at least in part to the failed war on drugs. The Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit that analyzes incarceration rates and their impacts on society, reports that some 2.3 million people are locked up in the American criminal justice system. The penal complex includes 3,163 local jails; 1,719 state prisons; 901 juvenile correctional facilities (talk about a euphemism); and 102 federal prisons, among others.

And capital punishment continues to be legal in a majority of states. In April, after a 12-year-long hiatus in executions, the state of Arkansas rushed to execute eight prisoners in 11 days. Why the hurry? It wasn’t a coincidence, and it wasn’t because the cases were connected or particularly heinous. It was because a controversial sedative used in the lethal injection, called midazolam, was about to pass its expiration date. Given highly visible problems with the drugs used in recent lethal injections in neighboring states, Arkansas had been worried that it wouldn’t be able to get replacement drugs in a timely fashion. In short, the rush to kill these men was about convenience and supply, not justice.

It’s an open question whether any state should ever have the legal right, much less moral consent and ethical blessing, to kill anyone. But capital punishment is currently the law of the land in much of the U.S. One would hope that execution schedules would get determined based on the merits of the cases, due process, and sufficient deliberation, not on the availability of drugs. Being forced to build a shelter in Siberia no longer seems so uncivilized.

Correction: February 7, 2023

An earlier version of this article referred to Konovalenko as a Russian artist rather than a Soviet artist.