Abortion Rights Are Being Eroded

The United States is now at a critical political and historical moment. An unprecedentedly regressive Republican political trifecta is poised to repeal rights to abortion. This includes attempts to reverse the landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade Supreme Court decision, which affirmed women’s right to abortion under the Constitution.

Rollbacks have already taken place after Republicans, driven by Tea Party activists, swept the 2010 midterm elections and reshaped state politics. Since Roe v. Wade more than four decades ago, 27 percent of all abortion restrictions were passed between 2010 and 2015. That’s more than in any other five-year period since the watershed ruling was enacted. More than half of all U.S. states now impose what critics view as unnecessary restrictions on clinics and/or abortion providers by, for example, legally requiring doctors to read scripts about fetal development or to show women fetal ultrasounds prior to an abortion, or by reducing the gestational age for legal abortion.

Nevertheless, federal mechanisms have provided vital defenses against further assaults to abortion rights. Former President Barack Obama’s administration continually blocked efforts to defund Planned Parenthood, and the Supreme Court upheld Roe in the face of broad challenges to it in 1992 and 2016. But things are set to change. After the conservative Supreme Court Justice Antonin Gregory Scalia passed away in 2016, Republicans delayed the nomination of a replacement until after the presidential election. President Donald Trump’s new appointee, conservative Justice Neil M. Gorsuch, is expected to back the president’s anti-abortion campaign promise. Other Republican appointees to the Supreme Court may well follow in the coming years if other justices retire or pass away; two of the current judges are aged 84 and 80.

Global impacts of this new administration’s anti-abortion stance are already being felt. On Trump’s fourth day in office, he reinstated—and extended—former President Ronald Reagan’s “global gag rule,” which prevents U.S.-funded international organizations from providing abortion care or information to women in need, even if they do so with money from other sources. His recent decision to cut funding to the U.N. Population Fund, which provides essential contraceptive and family planning services to women in at least 155 countries, also shows the long reach and global consequences of the Trump administration’s actions.

The right to a safe and accessible abortion is not just a women’s issue. The burden of both unwanted pregnancies and unsafe abortions falls heaviest on women, but it also affects partners and children who may find their life choices and opportunities compromised. When policies threaten the immediate and future health and well-being of women and families, we as a society suffer the consequences.

Proponents of greater abortion restrictions argue that recent regulations make abortion procedures safer by holding abortion clinics to the same (or higher) standard as surgical clinics, restricting abortion licenses to providers with hospital privileges, and providing women information about abortion risks that could persuade them to change their minds. Ensuring women’s health and well-being is a goal we all share. But these regulations don’t do that; they just make abortion harder to access and actually endanger pregnant women’s well-being.

First-trimester abortions, usually achieved through pharmaceuticals, have extremely low rates of complications; yet they are regulated much more stringently than far riskier medical procedures. Half of abortion clinics in Texas—most of which only provided pharmaceutical abortions—have been forced to close because they could not afford extensive and medically unnecessary renovations required of surgical centers, such as widening hallways and enlarging parking lots. Mandating wait times, reading out legislator-written scripts about fetal development, or forcing women to see an ultrasound of their fetus doesn’t change women’s minds if they have already made a decision; it just makes the abortion process more drawn out, expensive, and emotionally difficult for women and their doctors.

Read more from the archives: “We Should Talk More About the Abortion Pill.”

Laws that severely restrict abortion access do not decrease the use of abortion; rather, they just increase the frequency of unsafe and clandestine abortions. In El Salvador, which enacted a total abortion ban in 1998, unsafe abortions were the second leading cause of maternal mortality overall, according to estimates from the World Health Organization. Just as chilling, El Salvador’s Ministry of Health discovered that the third leading cause of maternal mortality is suicide, particularly among pregnant teenagers. Ethnographic accounts have also highlighted the suffering resulting from abortion bans. For example, in Romania and Poland, such bans led to clandestine pursuits of care, the criminalization of women and doctors, and infant abandonment.

Many of the legislators who urge restrictions to abortion based on false claims of safety simultaneously lobby to reduce public support for poorer mothers and to restrict funds for family planning. The Republican obsession with defunding Planned Parenthood, for example, willfully ignores the fact that abortion makes up only 3 percent of its total services; the vast majority of its federal dollars subsidize preventive services, such as contraceptives and mammograms, for low-income women. These conflicting agendas make clear that these politicians’ interest lies not in women’s well-being but in launching a targeted attack against reproductive freedoms.

Further abortion restrictions will disproportionately affect already disadvantaged groups. Overall, rates of abortion in the U.S. have declined during the past three decades due to access to sexual education and long-term contraception; abortion is increasingly concentrated among young and impoverished women with less access to sexual education and health care. Thirty-three states prohibit public funding for abortion care, so it is poor women and their families who must choose between ending an unintended pregnancy and paying for costs associated with education for various family members, making rent, or feeding existing children.

The current threat to abortion rights calls for immediate and sustained action on every level, from donating to organizations on the front lines of advocacy and care to disseminating research about the consequences of rollbacks and organizing long-term strategies to promote engaged and informed citizenship.

As part of our efforts to mount collective resistance, we need to better understand how Americans view issues of gender, personhood, the limits of scientific knowledge, and women’s rights, to name just a few. But there have been no in-depth U.S.-based ethnographic studies of abortion since anthropologist Faye D. Ginsburg’s landmark book Contested Lives: The Abortion Debate in an American Community was published in 1989. This represents a gaping hole in our understanding, and a weakness in our ability to fight back.

We need anthropologists and other social scientists to conduct ethnographic research on what happens to women whose access to timely abortion services is affected by these restrictions. We also need to engage with the worldviews of others to gain a better understanding of why anti-abortion rights rhetoric and activism remains so strong, even as support for other “liberal” issues like gay and transgender rights has become increasingly mainstream.

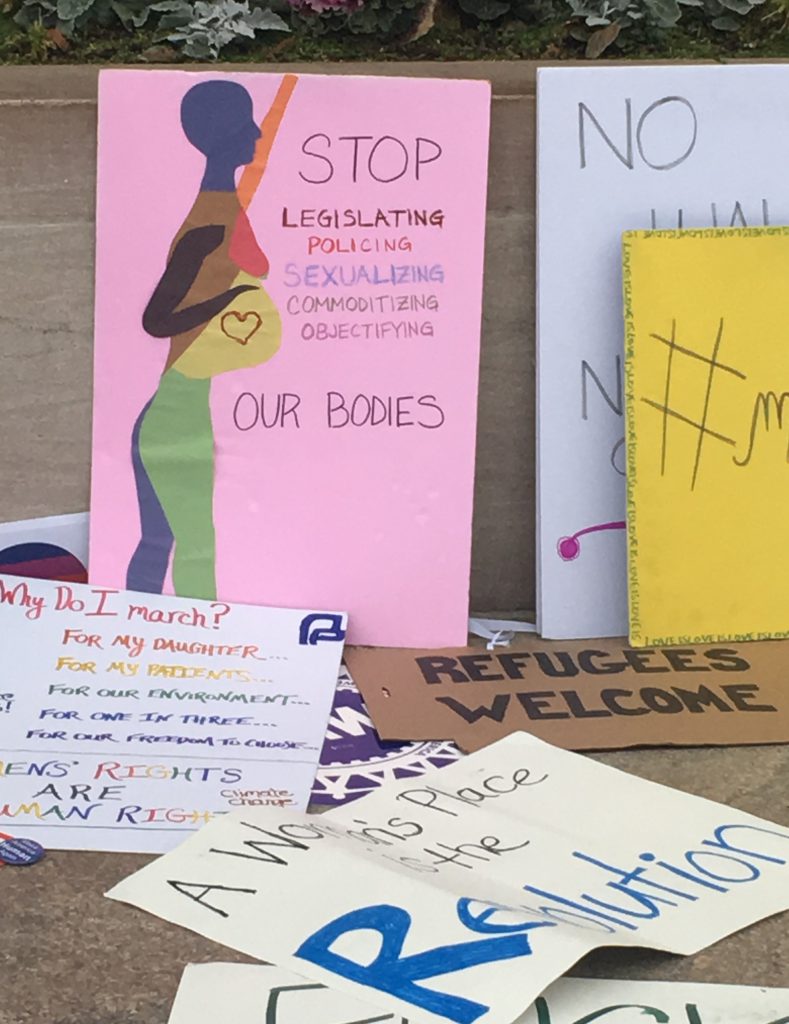

We should also collaborate with current social movements to forge a new and inclusive language of justice. In the past two decades, the pro-abortion rights movement has become increasingly isolated from other broad social movements. Too often, rights to abortion are defended through reference to various tragic circumstances of pregnancy: life endangerment, rape, incest, and congenital malformation. But this silences and stigmatizes the great majority of women whose reasons for obtaining an abortion do not fall into these categories. In this time of eroding rights, defenders of abortion rights must renew our efforts to show that safe and accessible abortion is a social good that is inextricable from broader issues of social equality and justice.

When the most vulnerable among us suffer the heaviest consequences, we must speak out. In the face of an administration bent on divide-and-conquer strategies of governance, we should all unite to defend abortion rights.