How Did We Ever Live Without GPS?

You’ve got to be very careful if you don’t know where you are going, because you might not get there.

—(attributed to) Yogi Berra

I’m writing this post while a passenger on Aeroflot (AFL) Flight 107 from Los Angeles to Moscow. I’m sitting in seat 5A, enjoying the creature comforts of business class, a personal first. The food is fantastic, the seat reclines into a fully flat bed, I’ve been given a bag of toiletries and nonmedicinal sleep aids, and the digital entertainment options are too numerous to count. From current news and sports to sitcoms and movies, one could make this flight a dozen times and sample only a fraction of the offerings. I skip the videos, put on the headphones, and fall asleep to one of my all-time favorite albums, Pink Floyd’s 1971 epic Meddle, while wondering how such an album found its way onto an Aeroflot flight in 2016. After sleeping so soundly, my jet-lag ends up worse during my first few days in Moscow than when I fly coach and can barely sleep at all. C’est la vie.

As a frequent flyer I always request a window seat and skip the movies and TV shows. As far as I am concerned, the best movie available on any plane (on a clear day) is an aerial view of Earth. It’s a great lesson in geomorphology (the study of landforms). As but one example, a left-window seat on the flight from Phoenix to Denver offers views of Arizona’s Meteor Crater and Canyon de Chelly, followed by Ship Rock in New Mexico and Mesa Verde in Colorado.

Window seats also provide insights into the archaeology of the modern world. From 40,000 feet one can see humankind’s ubiquitous footprint even in the sparsely populated American West. From sprawling cities and towns to the parallel tracks of the interstate highway system, I’ve watched the ebb-and-flow expansion of “civilization” follow the business cycle through boom and bust over the last several decades. Airborne, one can see oil- and gas-drilling pads, too numerous to count, multiplying like cancer cells across northwestern New Mexico, North Dakota, and Texas.

When window seats aren’t available (Yahweh forbid), I love to watch visualizations of the plane’s Global Positioning System (GPS) data to keep track of our progress. I first became enthralled by GPS presentations three decades ago on an Air France flight to Paris. I was amazed that passengers could see (be trusted with knowing?) the flight’s location, airspeed, elevation, and time remaining in flight. Three different allocentric (bird’s-eye-view) images at different scales (global, continental, national) rotated in sequence and at timed intervals, ultimately showing the plane’s position over and near specific cities. Back then, these images were presented on small movie screens in the aisles only when movies were not being shown. As clunky as it was, I was hypnotized—and hooked.

Fast-forward to today. Aeroflot’s presentation of GPS data provides a much richer, more vivid experience. In addition to old-school allocentric perspectives, I call up a digital version of what I am seeing out my window. I call up an image of what my fellow passengers are looking at out the right side of the plane. I call up an image of what the pilots are seeing from the cockpit, and I see the landform or body of water that’s directly beneath us. It’s nothing short of amazing.

When one steps back to think about the geopolitical implications of these systems and data, it becomes even more astonishing. When I first learned I would fly from Los Angeles to Moscow, I (incorrectly) assumed we were going to go west/northwest across Asia. How cool would that be? Oops.

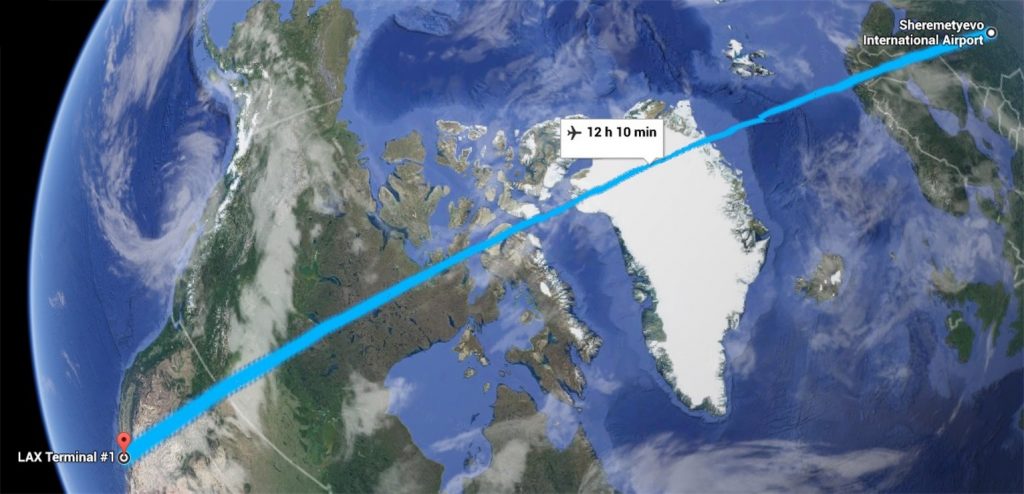

AFL 107’s flight path from LA to Moscow goes northeast out of southern California to enter a “Great Circle” that crosses Utah, Wyoming, Montana, Canada, Greenland, Norway, Sweden, and Finland. It then enters Russian airspace near St. Petersburg and proceeds southeast to land in Moscow’s northern suburbs.

The history of the now-ubiquitous Global Positioning System is deeply embedded in 20th-century Cold War politics. GPS was first developed for military applications, but President Ronald Reagan made it available for civilian use after the Soviet Air Force shot down Korean Air Lines (KAL) Flight 007 on September 1, 1983. A total of 269 people died in that tragic event, including a sitting U.S. congressman from Georgia. The political aftermath created the tensest moment of the Cold War after the Cuban missile crisis of 1962.

As difficult as it is to believe today, KAL 007 had a navigator in the cockpit whose job it was to triangulate and plot data coming in from radar and radio installations at intervals along its flight path. A single radar installation in Anchorage, Alaska, was down for maintenance. A small navigation error thus compounded over distance; KAL 007 was hundreds of miles off course and deep into Russian air space when it was shot down.

Today, GPS units in our cars and phones politely but firmly inform us when we’ve gone past a planned turn or destination. Indeed, we can determine our location at any given moment with a mind-boggling level of precision. I often wonder how we got along without GPS. Then again, people are really good at creating cognitive maps; it’s one of the things that makes us human. Over the next several posts, I will explore other types of maps and navigational tools. In the meantime, sit back, relax, and enjoy the astonishing presence of GPS in our lives.

Peanuts, anyone?