The Long Count

Time. Astronomers, philosophers, physicists, anthropologists, politicians, geographers, and theologians have all pondered the nature and meaning of time. Is it linear or cyclical? Is it reversible? (Put another way, can we go back in time?) Is time absolute and measurable, as it seemed to be to Isaac Newton and Galileo Galilei, or is it relative, as Albert Einstein theorized? Cynically, is it “what keeps everything from happening at once,” as science fiction author Ray Cummings wrote so memorably in 1923? Is time a cultural construct? Or is it a corollary to the second law of thermodynamics, under which disorder always increases? Why does time seem to go so much faster the older we get?

My conscious relationship with time was initially made manifest in the first clock I ever owned. I remember it well. My Westclox Baby Ben wind-up alarm clock had a slightly flattened oval face and elegant minute and hour hands with glow-in-the-dark stripes along their lengths. I remember having to wind it up each night before going to bed. I can still hear the rhythmic tick-tock sound of its fly wheel, and I can feel the small metal plunger button on the back right that turned off the loud alarm bell.

During my childhood, that Baby Ben reliably woke me up at 4:30 a.m. so that I could deliver the Chicago Tribune, rain or shine, on my paper route. The clock was tangible, analog, and irrefutable. I used it well into graduate school in the late 1980s.

Today, there are myriad ways of measuring and recording time. Our smartphones have stop watches that measure time in milliseconds, an absurd level of precision for daily life, but one that is increasingly important as we push the limits of human performance in fields such as Olympic swimming and auto racing. One of the many atomic clocks used to set International Atomic Time, a global standard, is based on vibrations in cesium-133 atoms and is so precise that it will take 1.4 million years for a cesium atomic clock to be off by a full second. Western societies are blessed, if not cursed, by ubiquitous clocks. Microwaves, coffee makers, pens, entertainment systems, and seemingly every other electronic device bears a digital clock.

Our lives weren’t always dictated by clock time. Until recently, the lives of agricultural, nomadic, and even urban peoples were governed by the seasonal round. As a result, many perceived time as cyclical, not linear. Even if they understood time to be linear, they may have been happy to measure it only with annual precision. Anything more refined than that was seen as overkill.

Since that time, cultural, economic, and political constructs have been put in place that many of us now take for granted, like standardized time zones, which were introduced in 1883 to coordinate cross-country rail service. Daylight saving time has an even more recent origin; it was not broadly and formally adopted in the United States until passage of the Uniform Time Act of 1966.

As intriguing as these constructs are, they are direct byproducts of capitalist expansion and economic development in North America. As an anthropologist, I am more interested in other cultural constructs surrounding time. Among my favorites are the winter counts kept by tribes, including the Blackfeet, Kiowa, Lakota, and Mandan, on the American Plains.

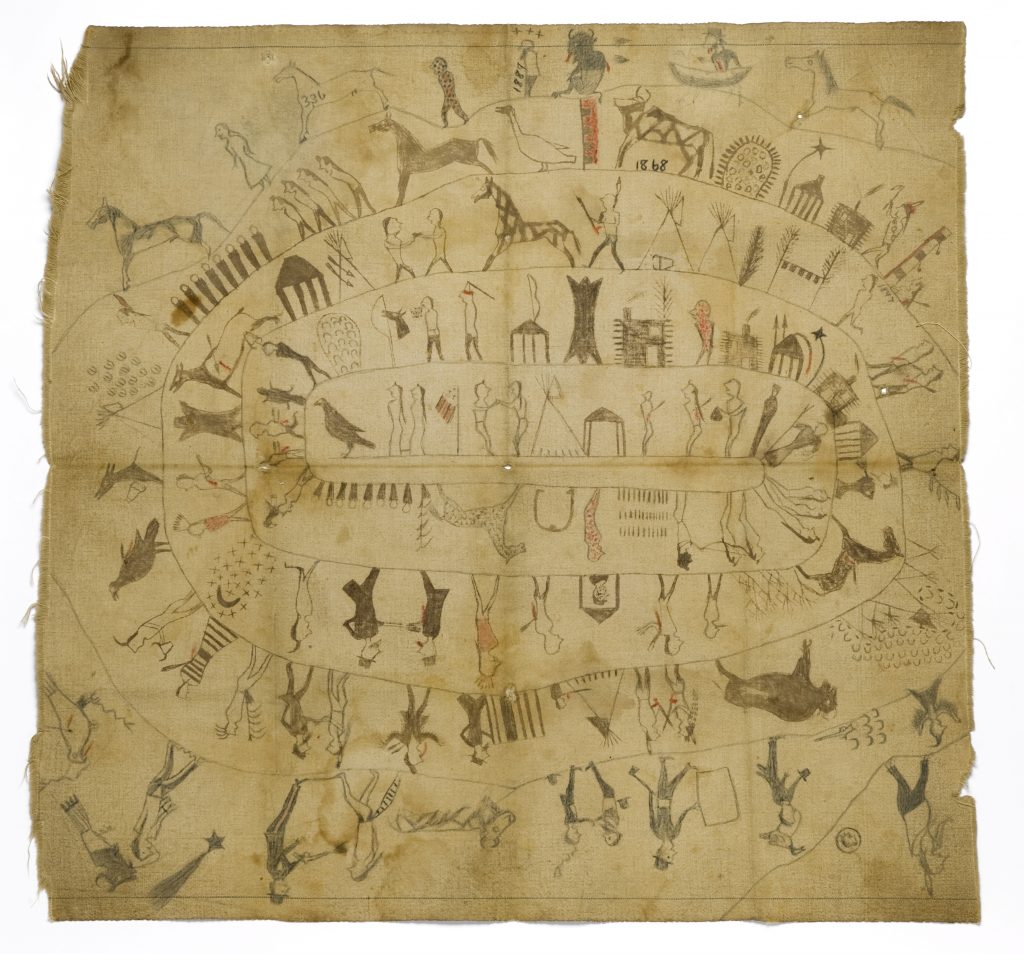

The Denver Museum of Nature & Science (DMNS) curates a Lakota winter count. It is a yellowing bolt of muslin measuring about 3 feet on a side. Illustrated with small symbolic images that spiral clockwise out from the center, it chronicles Lakota history from 1789 to 1910. Each of the 121 years in that period is marked by a single image. Calendars such as this are called “winter counts” because they were used to help the community recall important events in history during long winter nights.

The winter count in DMNS’ holdings is named after Lakota Chief Martin White Horse, its last keeper. His descendants had kept it as a family heirloom, and the museum purchased it from them in 1983. At that time, there were no documents associated with the count; curators were left to interpret the images as best they could.

In 2009, the museum got a call from Libby Holden of Edina, Minnesota. While sorting through family treasures, she and her relatives found a typewritten transcript titled “History of the Sioux Nation as told by Chief White Horse.” It turns out that in 1910 White Horse dictated an account of the winter count to Florence May Thwing, the wife of his attorney, George Thwing. After almost 100 years, the full, original meaning of the winter count could be studied.

Highlights of the chief’s explanation include 1834, “the year of stars moving in the sky”; 1891, the year of “the death of Sitting Bull”; and 1902, when “President William McKinley was assassinated by Leon Coloogz [sic Czolgosz].” The winter count is remarkable in that it provides a history of the Lakota people from their perspective during a time of dynamic cultural change. For his descendants, Chief Martin White Horse’s transcript represents more than a general recording of events, however. It represents a personal and tangible link with their past.

In an age when we are bombarded by data, the Lakota winter count is breathtaking in its simplicity, yet thought-provoking in its depth. It makes me wonder: How difficult would it be for us today to record history using only a single image for each year? Would 2016 be marked by the Chicago Cubs winning the World Series or by Donald Trump’s shocking presidential victory? How would we make that decision? If marking history is too difficult, what about autobiography? How might you record your life using one image per year?

In the end, the Lakota winter count reminds me that human beings have many different relationships with time, and at exactly 10:00 p.m. on November 12, I find comfort in that.

This article was republished on DiscoverMagazine.com.